Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A. (Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D.

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

“There are some parts of the world that, once visited, get into your heart and won’t go. For me, India is such a place. When I first visited, I was stunned by the richness of the land, by its lush beauty and exotic architecture, by its ability to overload the senses with the pure, concentrated intensity of its colours, smells, tastes, and sounds… I had been seeing the world in black & white and, when brought face-to-face with India, experienced everything re-rendered in brilliant Technicolor.” Keith Bellows, National Geographic Society :

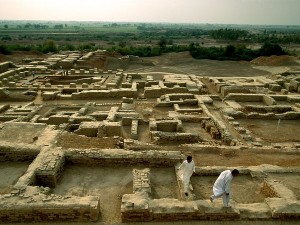

Indian architecture can be traced to the Indus Valley civilization. This mysterious culture emerged nearly 4,600 years ago and thrived for a thousand years, profiting from the highly fertile lands of the Indus River floodplain and trade with the civilizations of nearby Mesopotamia.

The city lacks ostentatious palaces, temples, or monuments. There’s no obvious central seat of government or evidence of a king or queen. Modesty, order, and cleanliness were apparently preferred. Pottery and tools of copper and stone were standardized. Seals and weights suggest a system of tightly controlled trade. The great Bath at Mohenjodaro is finely built brick structure with a layer of bitumen as waterproofing, and adjoining well that supplied water and an outlet that led to a large drain. Surrounding the bath are porticoes and set of rooms, while as stairway led to an upper level. The well planned residential areas were laid out on a grid pattern ,with main thoroughfares aligned north-south. The people lived in multi-roomed houses, with a bathing room which were connected to a street drain. An estimated 700 wells supplied Mohenjodaro residents with water and even the smallest house was connected to a drainage system. The impressive infrastructure of the Indus cities suggests an effective central authority. The Indus people adorned themselves with beads and ornaments of shell and terracotta, as well as silver and gold necklaces.

We have the brick ruins of Mohanjo-daro, but apparently the buildings of Vedic and Buddhist India were of wood, and Ashoka seems to have been the first to use stone for architectural purposes. We hear, in the literature, of seven- storied structures, and of palaces of some magnificence, but not a trace of them survives. Megasthencs describes the imperial residences of Chandragupta as superior to anything in Persia except Persepolis, on whose model they seem to have been designed. This Persian influence persisted till Ashoka’s time; it appears in the ground-plan of his palace, which corresponded with the “Hall of a Hundred Columns” at Persepolis; and it shows again in the fine pillar of Ashoka at Lauriya, crowned with a lion-capital.

With the conversion of Ashoka to Buddhism, Indian architecture began to throw off this alien influence, and to take its inspiration and it symbols from the new religion. The transition is evident in the great capital which is all that now remains of another Ashokan pillar, at Sarnath; ( The pillar is not located in it’s original location as it is broken during Turk and Islamic invasions. Now the Lion capital (National Emblem of Govt. of India) is displayed at the Archeological museum at Sarnath, km from Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh.) here, in a composition of astonishing perfection, ranked by Sir John Marshall as equal to “any thing of its kind in the ancient world,” The pillar is a symbol of the axis mundi (cosmic axis) and of the column that rises everyday at noon from the legendary Lake Anavatapta (the lake at the center of the universe according to Buddhist cosmology) to touch the sun.The top of the column—the capital—has three parts.

First, a base of a lotus flower, the most ubiquitous symbol of Buddhism.Then, a drum on which four animals are carved representing the four cardinal directions: a horse (west), an ox (east), an elephant (south), and a lion (north). They also represent the four rivers that leave Lake Anavatapta and enter the world as the four major rivers. Each of the animals can also be identified by each of the four perils of samsara. The moving animals follow one another endlessly turning the wheel of existence.

Four lions stand atop the drum, each facing in the four cardinal directions. Their mouths are open roaring or spreading the dharma, the Four Noble Truths, across the land. A cakra was originally mounted above the lions.Some of the lion capitals that survive have a row of geese carved below the lions. The goose is an ancient Vedic symbol. The flight of the goose is thought of as a link between the earthly and heavenly spheres.

The lotus or water-lily symbol migrated with Buddhism, and permeated the art of China and Japan. A like form, used as a design for windows and doors, became the “horseshoe arch” of Ashokan vaults and domes, originally derived from the “covered wagon” curvature of Bengali thatched roofs supported by rods of bent bamboo.

The religious architecture of Buddhist days has left us a few ruined temples and a large number -of “topes” and “rails.” The “tope” or “stupa” was in early days a burial mound; under Buddhism it became a memorial shrine, usually housing the relics of a Buddhist saint. Most often the tope took the form of a dome of brick, crowned with a spire, and surrounded with a stone rail carved with bas-reliefs. One of the oldest topes is at Bharhut; but the reliefs there are primitively coarse. The stupa of Bharhut is between Allahabad and Jabalpur situated in the erstwhile Nagod state of Madhya Pradesh. It was probably built around 150 B.C. The site was discovered by sir Alexander Cunningham in 1873. there are hardly any remains at the site now. Some of the remains of this stupa are kept in the Indian Museum in Calcutta.

The railings of the stupa are carved. These posts, railing, capping stones and gateways, all fashioned in deep red sandstone, once surrounded a stupa. The remarkable precision of the carvings and liveliness of the figures, narrative scenes and decorative themes testify to the vitality of India’s early artistic traditions. Many of the Bharhut posts are carved with yakshis which protrude in past relief; they stand in attitudes of devotion upon ganas or clutch branches of the tree. Here too are royal devotees, riders on horses and elephants, and even one example of a figure in foreign dress.

Other carved panels depict Buddhist narratives, among them the dream of Maya; celestials celebrating Buddha’s enlightenment, the worship of Buddha’s throne and the Bodhi tree; elephants paying homage to the Buddha throne; Naga king worshipping the throne and adoration of the wheel; and stupa in worship. Railing medallions display a variety of lotus design, sometimes incorporating in yaksha busts; other themes include Lakshmi bathed by elephants, scenes of everyday village life, deer, elephants and peacocks.

The most ornate of the extant rails is at Amaravati; The Great Stupa at Amaravati was a large Buddhist monument built in south-eastern India between the second century B.C. and the third century A.D. It was a centre for religious activity and worship for hundreds of years.. Here 17,000 square feet were covered with minute reliefs of a workmanship so excellent that Fergusson judged this rail to be “probably the most remarkable monument in India.”

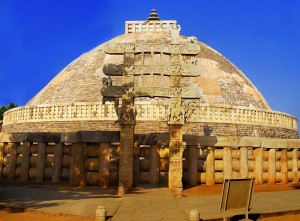

The best known of the stupas is the Sanchi Stupe, one of a group at Bhilsa in Bhopal. The ‘Great Stupa’ at Sanchi is the oldest stone structure in India and was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE. Its nucleus was a simple hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha. It was crowned by the chatra, a parasol-like structure symbolising high rank, which was intended to honour and shelter the relics. The construction work of this stupa was overseen by Ashoka’s wife, Devi herself, who was the daughter of a merchant of Vidisha. Sanchi was also her birthplace as well as the venue of her and Ashoka’s wedding. In the 1st century BCE, four profusely carved toranas or ornamental gateways and a balustrade encircling the whole structure was added The stone gates apparently imitate ancient wooden forms, and anticipate the pailus or torus that usually mark the approach to the temples of the Far East. Every foot of space on pillars, capitals, crosspieces and supports is cut into a wilderness of plant, animal, human and divine forms. On a pillar of the eastern gateway is a delicate carving of a perennial Buddhist symbol the Bodhi-tree, scene of the Master’s enlightenment; on the same gateway, gracefully spanning a bracket, is a sensuous goddess (a Yakshi) with heavy limbs, full hips, slim waist, and abounding breasts.

While the dead saints slept in the topes, the living monks cut into the mountain rocks temples where they might live in isolation, sloth and peace, secure from the elements and from the glare and heat of the sun. We may judge the strength of the religious impulse in India by noting that over twelve hundred of these cave-temples remain of the many thousands that were built in the early centuries of our era, partly for Jains and Brahmans, but mostly for Buddhist communities. Often the entrance of these viharas (monasteries) was a simple portal in the form of a “horseshoe” or lotus arch; sometimes, as at Nasik, it was an ornate facade of strong columns, animal capitals, and patiently carved architrave; often it was adorned with pillars, stone screens or porticoes of admirable design. The interior included a chaitya or assembly hall, with colonnades dividing nave from aisles, cells for the monks on either side, and an altar, bearing relics, at the inner end. One of the oldest of these cave-temples, and perhaps the finest now surviving, is at Karle, between Poona and Bombay; here Hinayana Buddhism achieved its chef-d’oeuvre.

During the Gupta period, the Golden Age of India, the caves of Ellora and Ajanta were dug out and frescoes painted. The caves are cut into the volcanic lava of the Deccan in the forest ravines of the Sahyadri Hills and are set in beautiful sylvan surroundings. These magnificent caves containing carvings that depict the life of Buddha, and their carvings and sculptures are considered to be the beginning of classical Indian art.

The 29 caves were excavated beginning around 200 BC, but they were abandoned in AD 650 in favour of Ellora. Five of the caves were temples and 24 were monasteries, thought to have been occupied by some 200 monks and artisans. The Ajanta Caves were gradually forgotten until their ‘rediscovery’ by a British tiger-hunting party in 1819.

The Ajanta site comprises thirty caves cut into the side of a cliff which rises above a meander in the Waghora River. Today the caves are reached by a road which runs along a terrace mid-way up the cliff, but each cave was once linked by a stairway to the edge of the water. This is a Buddhist community, comprising five sanctuaries or Chaitya-grihas (caves 9, 10, 19, 26 and 29) and monastic complex sangharamas or viharas.The Mighty caves of Ellora were carve out of solid rock with the stupendous Kailasa temple in the center; it is difficult to imagine how human beings conceived this or having conceived it, gave body and shape to their conception. The caves of Elephanta, with the powerful and subtle Trimurti, date also to this period.

“Stupendous work,” wrote British artist James Wales in 1792 of his first view of the Buddhist rock cave temple at Karli. Carved in the face of the Western Ghats, the steep hills separating the coastal plain and the central plateau southeast of Bombay, the temple dated from the first century A.D. Unlike anything Wales had ever seen before, Karli, along with other cave complex in the area, had been hollowed out of the rock by Hindus, Buddhists and Jains as places of worship and monastic residence through the ages.

The caves at Ajanta, besides being the hiding-place of the greatest of Buddhist paintings, rank with Karle as examples of that composite art, half architecture and half sculpture, which characterizes the temples of India. Caves I and II have spacious assembly halls whose ceilings, cut and painted in sober yet elegant designs, are held up by powerful fluted pillars square at the base, round at the top, ornamented with flowery bands, and crowned with majestic capitals; Cave XIX is distinguished by a fagade richly decorated with adipose statuary and complex bas-relief s; in Cave XXVI gigantic columns rise to a frieze crowded with figures which only the greatest religious and artistic zeal could have carved in such detail. Ajanta can hardly be refused the title of one of the major works in the history of art. The Ajanta frescoes are very beautiful. They take one back to some distant dream-like and yet very real world.

Of other Buddhist temples still existing in India the most impressive is the great tower at Bodh-gaya, significant for its thoroughly Gothic arches, and yet dating, apparently, back to the first century A.D. All in all, the remains of Buddhist architecture arc fragmentary, and their glory is more sculptural than structural; a lingering Puritanism, perhaps, kept them externally forbidding and bare. The Jains gave a more concentrated devotion to architecture, and during the eleventh and twelfth centuries their temples were the finest in India. They did not create a style of their own, being content to copy at first (as at Elura) the Buddhist plan of excavating temples in the mountain rocks, then the Vishnu or Shiva type of temples rising usually in a walled group upon a hill. These, too, were externally simple, out inwardly complex and rich a happy symbol of the modest life. Piety placed statue after statue of Jain heroes in these shrines, until in the group at Shatrunjaya Fergusson counted 6449 figures.

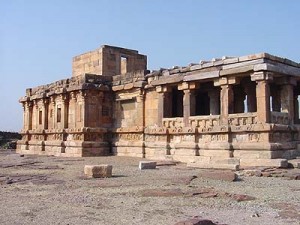

The Jain temple at Aihole is built almost in Greek style, with rectangular form, external colonnades, a portico, and a cell or central chamber within. Aihole is considered the cradle of Hindu and Jain temple architecture. During the 5th Century A.D., this place was a great centre of trade, education and religion.

The architectural range seen in the temples of Aihole, is reflective of the early experimental phase of development of the Hindu & Jain style of temple architecture, as it evolved from simple rock cut shrines to large and complicated structures.

The Jain & Hindu temples of Badami, Patadakal & Aihole shows the unique architectural style of that period. Aihole is dotted with more than one hundred structures, testimonials to the experiments undertaken by the Chalukyan architects towards the evolution of the Hindu & Jain style of temple architecture. The fully evolved temples are manifestations of the embryonic stages of the South Indian (Dravidian) style of temple architecture that fully developed later on. Each of the early temples at Aihole has its own architectural feature.

There are almost 125 stone temples and two cave temples, divided into 22 groups scattered around the village out of which the Durga Temple, Lad Khan Temple & Meguti Temple are the most impressive. The Meguti Jain Temple is prominently located on top of the highest hill in Aihole and was built in the year 634 AD. The Meguti temple, situated on the hillock, is built on an elevated platform. It has two sanctums, a court hall and a portico. A stone ladder carved out at the portico provides access to the roof. This flight of stairs leads to another shrine on the roof, directly above the main shrine. From the roof, one can have a panoramic view of the hundred temples of Aihole. A pillared corridor runs around the temple, enveloping the shrine. Its beautiful motifs and richly carved images on stone reflect the earliest development of Jain a art and architecture.

At Khajuraho Jains, Vaishnavites and Shivaites, as if to illustrate Hindu tolerance, built in close proximity some twenty-eight temples; among them the almost perfect Temple of Parshwanath rises in cone upon cone to a majestic height, and shelters on its carved surfaces a veritable city of Jain saints.

On Mt. Abu, lifted four thousand feet above the desert, the Jains built many temples, of which two survivors, the temples of Vimala and Tejahpala, are the greatest achievement of this sect in the field of art. The dome of the Tejahpala shrine is one of those overwhelming experiences which doom all writing about art to impotence and futility. The Temple of Vimala, built entirely of white marble, is a maze of irregular pillars, joined with fanciful brackets to a more simple carved entablature; above is a marble dome too opulent in statuary, but carved into a stone lacework of moving magnificence, “finished,” says Fergusson, “with a delicacy of detail and appropriateness of ornament which is probably unsurpassed by any similar example to be found anywhere else.

In these Jain temples, and their contemporaries, we see the transition from the circular form of the Buddhist shrine to the tower style of medieval India. The nave, or pillar-enclosed interior, of the assembly hall is taken outdoors, and made into a mandapam or porch; behind this is the cell; and above the cell rises, in successively receding levels, the carved and complicated tower. It was on this plan that the Hindu temples of the north were built. The most impressive of these is the group at Bhuvaneshwara, in the province of Orissa; and the finest of the group is the Rajarani Temple erected to Vishnu in the eleventh century A.D. It is a gigantic tower formed of juxtaposed semi- circular pillars covered with statuary and surmounted by receding layers of stone, the whole inward-curving tower ending in a great circular crown and a spire. Nearby is the Lingaraja Temple, larger than the Rajarani, but not so beautiful; nevertheless every inch of the surface has felt the sculptor’s chisel, so that the cost of the carving has been reckoned at three times the cost of the structure. The Hindu expressed his piety not merely by the imposing grandeur of his temples, but by their patiently worked detail; nothing was too good for the god.

The Nelliyappar temple chronicle, Thirukovil Varalaaru, says the nadaththai ezhuppum kal thoongal — stone pillars that produce music — were set in place in the 7th century during the reign of Pandyan king Nindraseer Nedumaran. Archaeologists date the temple before 7th century and say it was built by successive rulers of the Pandyan dynasty that ruled over the southern parts of Tamil Nadu from Madurai. Tirunelveli, about 150 km south of Madurai, served as their subsidiary capital

Shiva is the Destroyer and Lord of Rhythm in the Hindu trinity. But here he is Lord Nellaiyappar, the Protector of Paddy, as the name of the town itself testifies — nel meaning paddy and veli meaning fence in Tamil. Prefixed to nelveli is tiru, which signifies something special — like the exceptional role of the Lord of Rhythm or the unique musical stone pillars in the temple.In the Nellaiyappar temple, gentle taps on the cluster of columns hewn out of a single piece of rock can produce the keynotes of Indian classical music. “Hardly anybody knows the intricacies of how these were constructed to resonate a certain frequency. The more aesthetically inclined with some musical knowledge can bring out the rudiments of some rare ragas from these pillars.”

In Shiva’s temple, stone pillars make music – an architectural rarity Each huge musical pillar carved from one piece of rock comprises a cluster of smaller columns and stands testimony to a unique understanding of the “physics and mathematics of sound.” Well-known music researcher and scholar Prof. Sambamurthy Shastry, the “marvellous musical stone pillars” are “without a parallel” in any other part of the country. “What is unique about the musical stone pillars in the Tiruelveli Nellaiyappar temple is the fact you have a cluster as large as 48 musical pillars carved from one piece of stone, a delight to both the ears and the eyes,” The pillars at the Nellaiyappar temple are a combination of the Shruti and Laya types.

It would be dull to list, without specific description and photographic representation, the other masterpieces of Hindu building in the north. And yet no record of Indian civilization could leave unnoticed the temples of Surya at Kanarak and Mudhera, the tower of Jagannath Puri, the lovely gateway at Vadnagar, the massive temples of Sas-Bahu and Teli-ka-Mandir at Gwalior, the palace of Rajah Man Sing, also at Gwalior, and the Tower of Victory at Chitor. Standing out from the mass are the Shivaite temples at Khajuraho, while in the same city the dome of the porch of the Khanwar Math Temple shows again the masculine strength of Indian architecture, and the richness and patience of Indian carving. Even in its ruins the Temple of Shiva at Elephanta, with its massive fluted columns, its “mushroom” capitals, its un- surpassed reliefs, and its powerful statuary, suggests to us an age of national vigour and artistic skill of which hardly the memory lives today.

We shall never be able to do justice to Indian art, for ignorance and fanaticism have destroyed its greatest achievements, and have half ruined the rest. At Elephanta the Portuguese certified their piety by smashing statuary and bas-reliefs in unrestrained barbarity; and almost everywhere in the north the Moslems brought to the ground those triumphs of Indian architecture, of the fifth and sixth centuries, which tradition ranks as far superior to the later works that arouse our wonder and admiration today. The Moslems decapitated statues, and tore them limb from limb; they appropriated for their mosques, and in great measure imitated, the graceful pillars of the Jain temples. Time and fanaticism joined in the destruction, for the orthodox Hindus abandoned and neglected temples that had been profaned by the touch of alien hands.

We may guess at the lost grandeur of north Indian architecture by the powerful edifices that still survive in the south, where Moslem rule entered only in minor degree, and after some habituation to India had softened Mohammedan hatred of Hindu ways. Further, the great age of temple architecture in the south came in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, after Akbar had tamed the Moslems and taught them some appreciation of Indian art. Consequently the south is rich in temples, usually superior to those that remain standing in the north, and more massive and impressive; Fergusson counted some thirty “Dravidian” or southern temples any one of which, in his estimate, must have cost as much as an English cathedral. The south adapted the styles of the north by prefacing the mandapann or porch with a gopuram or gate, and supporting the porch with a lavish multiplicity of pillars. It played fondly with a hundred symbols, from the swastika emblem of the sun and the wheel of life, through a very menagerie of sacred animals. The snake, through its moulting, symbolized reincarnation; the bull was the enviable paragon of procreative power; the linga, or phallus, represented the generative excellence of Shiva, and often determined the form of the temple itself.

Three elements composed the structural plan of these southern temples: the gateway, the pillared porch, and the tower (vimand), which contained the main assembly hall or cell. With occasional exceptions like the palace of Tirumala Nayyak at Madura, all this south Indian architecture was ecclesiastical. Men did not bother to build magnificently for themselves, but gave their art to the priests and the gods; no circumstance could better show how spontaneously theocratic was the real government of India. Of the many buildings raised by the Chalukyan kings and their people, nothing remains but temples. Only a Hindu pietist rich in words could describe the lovely symmetry of the shrine at Ittagi, in Hyderabad; or the temple at Somnathpur in Mysore, in which gigantic masses of stone are carved with the delicacy of lace; or the Hoyshaleshwara Temple at Halebid, also in Mysore “one of the buildings,” says Fergusson, “on which the advocate of Hindu architecture would desire to take his stand.” Here, he adds, “the artistic combination of horizontal with vertical lines, and the play of outline and of light and shade, far surpass anything in Gothic art. The effects are just what the medieval architects were often aiming at, but which they never attained so perfectly as was done at Halebid.”

Halebidu was the 12th century capital of the Hoysalas. The Hoysaleswara temple was built during this time by Ketamala and attributed to Vishnuvardhana, the Hoysala ruler. It enshrines Hoysaleswara and Shantaleswara, named after the temple builder Vishnuvardhana Hoysala and his wife, Queen Shantala.

Then it was sacked by the armies of Malik Kafur in the early 14th century, after which it fell into a state of disrepair and neglect.

The temple complex comprises two Hindu temples, the Hoysaleshawara and Kedareshwara temples and two Jain basadi. In front of these temples there is a big lake. The town gets its name from the lake, Dwara samudhra which means entrance from ocean[The two Nandi statues which are on the side of the Hoysaleshwara temple are monolithic. Soap stone or Chloritic Schist was used for the construction of these temples. However a number of sculptures in the temple are destroyed by invaders. So the temple is incomplete. Halebid means old abode. There is an archeological museum in the temple complex.

The Hoysaleswara temple, dating back to the 1121 C.E., is astounding for its wealth of sculptural details. The walls of the temple are covered with an endless variety of depictions from Hindu mythology, animals, birds and Shilabalikas or dancing figures. Yet no two sculptures of the temple are the same. This magnificent temple guarded by a Nandi Bull was never completed, despite 86 years of labour. The Jain basadi nearby are equally rich in sculptural detail.

If we marvel at the laborious piety that could carve eighteen hundred feet of frieze in the Halebid temple, and could portray in them two thousand elephants each different from all the rest,” what shall we say of the patience and courage that could undertake to cut a complete temple out of the solid rock? But this was a common achievement of the Hindu artisans. At Mamallapuram, on the east coast near Madras, they carved several rathas or pagodas, of which the fairest is the Dharma-raja-ratha, or monastery for the highest discipline. At Elura, a place of religious pilgrimage in Hyderabad, Buddhists, Jains and orthodox Hindus vied in excavating out of the mountain rock great monolithic temples of which the supreme example is the Hindu shrine of Kailasha named after Shiva’s mythological paradise in the Himalayas. Here the tireless builders cut a hundred feet down into the stone to isolate the block 250 by 160 feet that was to be the temple; then they carved, the walls into powerful pillars, statues and bas-reliefs; then they chiseled out the interior, and lavished there the most amazing art: let the bold fresco of “The Lovers” serve as a specimen. Finally, their architectural passion still unspent, they carved a series of chapels and monasteries deep into the rock on three sides of the quarry. Some Hindus consider the Kailasha Temple equal to any achievement in the history of art.

Such a structure, however, was a tour de force, like the Pyramids, and must have cost the sweat and blood of many men. Either the guilds or the masters never tired, for they scattered through every province of southern India gigantic shrines so numerous that the bewildered student or traveller loses their individual quality in the sum of their number and their power.

Here, says Meadows Taylor, “the carving on some of the pillars, and of the lintels and architraves of the doors, is quite beyond description. No chased work in silver or gold could possibly be finer. By what tools this very hard, tough stone could have been wrought and polished as it is, is not at all intelligible at the present day.”

At Pattadakal Queen Lokamahadevi, one of the wives of the Chalukyan King Vikramaditya II, dedicated to Shiva the Virupaksha Temple, which ranks high among the great fanes of India. At Tan j ore, south of Madras, the Chola King Rajaraja the Great, after conquering all southern India and Ceylon, shared his spoils with Shiva by raising to him a stately temple designed to represent the generative symbol of the god. Near Trichinopoly, west of Tanjore, the devotees of Vishnu erected on a lofty hill the Shri Rangam Temple, whose distinctive feature was a many-pillared mandapam in the form of a “Hall of a Thousand Columns,” each column a single block of granite, elaborately carved; the Hindu artisans were yet at work completing the temple when they were scattered, and their labours ended, by the bullets of Frenchmen and Englishmen fighting for the possession of India. 108 Nearby, at Madura, the brothers Muttu and Tirumala Nayyak erected to Shiva a spacious shrine with another Hall of a Thousand Columns, a Sacred Tank, and ten gopurams or gateways, of which four rise to a great height and are carved into a wilderness of statuary. These structures form together one of the most impressive sights in India; we may judge from such fragmentary survivals the rich and spacious architecture of the Vijayanagar kings. Finally, at Rameshvaram, amid the archipelago of isles that pave “Adam’s Bridge” from India to Ceylon, the Brahmans of the south reared through five centuries a temple whose perimeter was graced with the most imposing of all corridors or porticoes four thousand feet of double colonnades, exquisitely carved, and designed to give cool shade, and inspiring vistas of sun and sea, to the millions of pilgrims who to this day find their way from distant cities to lay their hopes and grieves upon the knees of the gods.

References

COOMARASAVAMY, ANANDAK.: History of Indian and Indonesian Art. New York, 1927.

CANDEE, HELEN: Angkor the Magnificent. New York, 1924

CHIROL, SIR VALENTINE: India. London, 1926.

GANGOLY, O. C.: Indian Architecture. Calcutta, n.d.

GANGOLY, O. C.: Art of Java. Calcutta, n.d.

HAVELL, E. B.: Ancient and Medieval Architecture of India. London, 1915.

HAVELL, E. B.: Ideals of Indian Art. New York, 1920.

HAVELL, E. B.: History of Aryan Rule in India. Harrap, London, n.d.

FRAZER, R. W.: Literary History of India. London, 1920.

FISCHER, OTTO: Die Kunst Indiens, Chinas und Japans. Berlin, 1928.

FERGUSON, J. G: Outlines of Chinese Art. University of Chicago, 1919.

FRGUSSON, JAS.: History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, 2V. London, 1910.

FERGUSSON, JAS.: History of Architecture in All Countries. 2V. London, 1874.

LORENZ, D. E.: The ‘Round the World Traveler. New York, 1927.

LOTI, PIERRE: India. London, 1929.

MACDONELL, A. A.: History of Sanskrit Literature. New York, 1900.

MACDONELL, A. A.: India’s Past. Oxford, 1927.

MUKERJI, D. G.: A Son of Mother India Answers. New York, 1928.

MUKERJI, D. G.: Visit India with Me. New York, 1929.

SMITH, G. ELLIOT: Human History. New York, 1929.

SMITH, W. ROBERTSON: The Religion of the Semites. New York, 1889.

SMITH,V. A.: Asoka. Oxford, 1920.

WILL DURANT: Our Oriental Heritage. Simon and Schuster. New York 1954