Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A. (Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D.

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Mrs Sudha Rani Maheshwari, M.Sc (Zoology), B.Ed.

Former Principal. A.K.P.I.College, Roorkee, India

In the days when historians supposed that history had begun with Greece, Europe gladly believed that India had been a hotbed of barbarism until the “Aryan” cousins of the European peoples had migrated from the shores of the Caspian to bring the arts and sciences to a savage and benighted peninsula. Recent researches have marred this comforting picture as future researches will change the perspective of these pages. In India, as elsewhere, the beginnings of civilization are buried in the earth, and not all the spades of archaeology will ever quite exhume them. Remains of an Old Stone Age fill many cases in the museums of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay; and Neolithic objects have been found in nearly every state. These, however, were cultures, not yet a civilization.

In 1924 the world of scholarship was again aroused by news from India: Sir John Marshall announced that his Indian aides, R. D. Banerji in particular, had discovered at Mohenjo-daro, on the western bank of the lower Indus, remains of what seemed to be an older civilization than any yet known to historians. There, and at Harappa, a few hundred miles to the north, four or five superimposed cities were excavated, with hundreds of solidly-built brick houses and shops, ranged along wide streets as well as narrow lanes, and rising in many cases to several stories. Let Sir John estimate the age of these remains:

These discoveries establish the existence in Sind (the northernmost province of the Bombay Presidency) and the Punjab, during the fourth and third millennium B.C., of a highly developed city life; and the presence, in many of the houses, of wells and bathrooms as well as an elaborate drainage-system, betoken a social condition of the citizens at least equal to that found in Sumer, and superior to that prevailing in contemporary Babylonia and Egypt. . . . Even at Ur the houses are by no means equal in point of construction to those of Mohenjo-Daro.

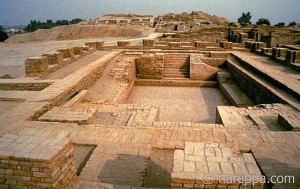

The ruins of the huge city of Mohenjo-Daro – built entirely of unbaked brick in the 3rd millennium B.C. – lie in the Indus valley. The acropolis, set on high embankments, the ramparts, and the lower town, which is laid out according to strict rules, provide evidence of an early system of town planning.

Mohenjo-Daro is the most ancient and best-preserved urban ruin on the Indian subcontinent, dating back to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, and exercised a considerable influence on the subsequent development of urbanization on the Indian peninsula.

The archaeological site is located on the right bank of the Indus River, 400 km from Karachi, in Pakistan’s Sind Province. It flourished for about 800 years during the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. Centre of the Indus Civilization, one of the largest in the Old World, this 5,000-year-old city is the earliest manifestation of urbanization in South Asia. Its urban planning surpasses that of many other sites of the oriental civilizations that were to follow.

Of massive proportions, Mohenjo-Daro comprises two sectors: a stupa mound that rises in the western sector and, to the east, the lower city ruins spread out along the banks of the Indus. The acropolis, set on high embankments, the ramparts, and the lower town, which is laid out according to strict rules, provide evidence of an early system of town planning.

The stupa mound, built on a massive platform of mud brick, is composed of the ruins of several major structures – Great Bath, Great Granary, College Square and Pillared Hall – as well as a number of private homes. The extensive lower city is a complex of private and public houses, wells, shops and commercial buildings. These buildings are laid out along streets intersecting each other at right angles, in a highly orderly form of city planning that also incorporated important systems of sanitation and drainage.

Of this vast urban ruin of Mohenjo-Daro, only about one-third has been reveal by excavation since 1922. The foundations of the site are threatened by saline action due to a rise of the water table of the Indus River. This was the subject of a UNESCO international campaign in the 1970s, which partially mitigated the attack on the prehistoric mud-brick buildings.

Among the finds at these sites were household utensils and toilet out- fits; pottery painted and plain, hand-turned and turned on the wheel; terracotta’s, dice and chess-men; coins older than any previously known; over a thousand seals, most of them engraved, and inscribed in an un- known pictographic script; faience work of excellent quality; stone carving superior to that of the Sumerians; copper weapons and implements, and a copper model of a two-wheeled cart (one of our oldest examples of a wheeled vehicle) ; gold and silver bangles, ear-ornaments, necklaces, and other jewellery “so well finished and so highly polished,” says Marshall, “that they might have come out of a Bond Street jeweller’s of today rather than from a prehistoric house of 5,000 years ago.”

Strange to say, the lowest strata of these remains showed a more developed art than the upper layers as if even the most ancient deposits were from a civilization already hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years old. Some of the implements were of stone, some of copper, some of bronze, suggesting that this Indus culture had arisen in a Chalcolithic Age i.e., in a transition from stone to bronze as the material of tools.” The indications are that Mohenjo-Daro was at its height when Cheops built the first great pyramid; that it had commercial, religious and artistic connections with Sumeria and Babylonia; and that it survived over three thousand years, until the third century before Christ, These connections are suggested by similar seals found at Mohenjo-Daro and in Sumeria (especially at Kish), and by the appearance of the Naga, or hooded serpent, among the early Mesopotamian seals. u In 1932 Dr. Henri Frankfort unearthed, in the ruins of a Babylonian-Elamite village at the modern Tell-Asmar (near Baghdad), pottery seals and beads which in his judgment (Sir John Marshall concurring) were imported from Mohenjo-Daro ca. 2000 B.C.”

Macdone.U believes that this amazing civilization was derived from Sumeria;” Hall believes that the Sumerians derived their culture from India;” Woolley derives both the Sumerians and the early Hindus from some common parent stock and culture in or near Baluchistan. Investigators have been struck by the fact that similar seals found both in Babylonia and in India belong to the earliest (“pre-Sumerian”) phase of the Mesopotamian culture, but to the latest phase of the Indus civilization which suggests the priority of India. Guide inclines to this conclusion: “By the end of the fourth millennium B.C. the material culture of Abydos, Ur, or Mohenjo-Daro would stand comparison with that of Periclean Athens or of any medieval town. . . . Judging by the domestic architecture, the seal-cutting, and the grace of the pottery, the Indus civilization was ahead of the Babylonian at the beginning of the third millennium (ca. 3000 B.C.). But that was a late phase of the Indian culture; it may have enjoyed no less lead in earlier times. Were then the innovations and discoveries that characterize proto-Sumcrian civilization not native developments on Babylonian soil, but the results of Indian inspiration? If so, had the Sumerians themselves come from the Indus, or at least from regions in its immediate sphere of influence?” These fascinating questions cannot yet be answered; but they serve to remind us that a history of civilization, because of our human ignorance, begins at what was probably a late point in the actual development of culture.

We cannot tell yet whether, as Marshall believes, Mohenjo-Daro represents the oldest of all civilizations known. But the exhuming of prehistoric India has just begun; only in our time has archaeology turned from Egypt across Mesopotamia to India. When the soil of India has been turned up like that of Egypt we shall probably find there a civilization older than that which flowered out of the mud of the Nile. Excavations near Chitaldrug, in Mysore, revealed six levels of buried cultures, rising from Stone Age implements and geometrically adorned pottery apparently as old as 4000 B.C., to remains as late as 1200 A.D.”

REFERANCES

CHILDE, V. GORDON: The Most Ancient East. London, 1928.

MARSHALL, SIR JOHN: Prehistoric Civilization of the Indus. Illustrated Lon- don News, Jan. 7, 1928.

MUTHU, D. G: The Antiquity of Hindu Medicine and Civilization. London

WILL DURANT: Our Oriental Heritage. Simon and Schuster. New York 1954

WOOLLEY, C. LEONARD: The Sumerians. Oxford, 1928