Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Hilda Taba is known worldwide as an outstanding American educator and curriculum theorist, she was born, brought up and educated in Estonia. Taba, belongs to the list of the most outstanding educators of the twentieth century.

Taba’s theoretical ideas and thinking, was the collision between German and American educational traditions that she experienced in her studies of pedagogy. For instance, the undergraduate educational preparation that she received at the University of Tartu had a strong disposition towards German didactics and educational philosophy. However, her subsequent post-graduate studies in the United States of America were strongly influenced by the ideas of progressive education, which she came to admire and which became a cornerstone of her educational thinking.

Hilda Taba’s road to excellence was in some parts due to chance, her enormous desire to succeed and the favourable conditions for educational research in the United States, and she became one of the brightest stars in the educational constellation of the 1960s. Nowadays, her work in the field of curriculum design, alongside that of Ralph W. Tyler, belongs to the classics of pedagogy. Several contemporary authors still frequently refer to Hilda Taba’s ideas and base their work in the field of curriculum theory and practice on her conceptions developed decades ago.

As far as the personality of Hilda Taba , Elizabeth H. Brady’s one of her closest colleagues during the days of intergroup education projects , wrote: ‘Taba was very energetic, enthusiastic, active, seemingly tireless; she led life at a tempo which sometimes led to misunderstandings and often wore out friends and staff. She was small in stature, perky in manners and in dress, and always intent on the next thing’.

Hilda Taba’s childhood and university studies

The future prominent educator Hilda Taba was born in Kooraste, a small village in the present Põlva county, in south-east Estonia, on 7 December 1902. She was the first of nine children of Robert Taba, a schoolmaster. Hilda was first educated at her father’s elementary school, and then at the local parish school.

In 1921, after graduating from Võru High School for Girls, she decided to become an elementary school-teacher, but she did not begin work at a primary school. Instead, she became a student of economics at the University of Tartu. Economics, however, did not appeal to Taba and a year later she applied to be transferred to the Faculty of Philosophy where she majored in history and education

After graduating from the University of Tartu in 1926, Taba had the opportunity to undertake her post-graduate studies in the United States, supported by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. Her excellent knowledge of educational subjects acquired at Tartu University made it possible for her to complete a master’s degree at Bryn Mawr College in a year. During her studies at Bryn Mawr, she started to visit progressive schools and became interested in the practice of the Dalton Plan . Surveying American educational literature, Taba discovered Fundamentals of education by Boyd. H. Bode , a then widely known author and educator in the United States. Taba was very impressed by Bode’s approach and she grew interested in the philosophy of progressive education. In particular, she enjoyed the child-centeredness and the novelty and flexibility of this educational approach.

In 1927 she applied for doctoral studies in educational philosophy at Columbia University. During the following five years of studies Taba met many American scientists of world renown, among them the psychologist E.L. Thorndike , the educator and historian P. Monroe , the sociologist G.C. Gounts, and the founder of the Winnetka Plan, C. Washburne . The principal advisor of her doctoral work became William H. Kilpatrick , one of John Dewey’s colleagues, known in the history of education as the initiator of the project method. Kilpatrick ended his foreword to Taba’s dissertation with prophetic words about its author, stating that ‘hard will be that reader to please and far advanced his previous thinking who does not leave this book feeling distinctly indebted to its very capable author’.

Hilda Taba’s scientific career

In the United States, in 1933 Taba was given a post as a German teacher, and later on she became the director of curriculum in the Dalton School, in Ohio.

Hilda Taba became involved in educational research by a lucky chance. She was hired just at the start of the Eight-Year Study in which the Dalton School was actively involved. Taba’s participation in the study brought her together with Ralph Tyler, who was the head of the field evaluation staff of the study.

In 1939, when the evaluation staff was transferred to the University of Chicago, Taba became the director of the curriculum laboratory, which she headed until 1945.

By the mid-1940s Taba had become a capable and widely recognized educational researcher. She initiated, designed and directed several research projects centered on two major topics: intergroup education (1945–51); and the reorganization and development of social studies curricula in California (1951–67). Hilda Taba also served as a consultant to many local institutions and school districts, and she took part in UNESCO seminars in Paris and Brazil.

Studies in the field of intergroup Education

Intergroup education became topical in the United States following the Second World War. Taba’s research group submitted to the American Council on Education one of many proposals aimed at the investigation of possibilities for increasing the level of tolerance between students from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The Intergroup Education Project was accepted and launched in New York City in 1945. Hilda Taba became its director. The success of the experimental project led to the establishment of the Center of Intergroup Education at the University of Chicago, which was headed by Taba (1948– 51).

Elizabeth H. Brady’s comment that one of Taba’s ‘major contributions was to recognize that social science could provide a strong foundation for education, with sociology, social pedagogy and cultural anthropology in particular illuminating issues in human relations education’.

Development of Social Studies Curricula

The second and final period of Hilda Taba’s independent scientific career began in 1951, she became a full professor of education at San Francisco State University. This was the period when her expertise in the areas of curriculum design, inter group education and development of cognitive processes won her international recognition.

Taba saw the problems connected with the social studies curriculum and the reasons for selecting a specific strategy for curriculum development in this way: The analysis of the problems required change in the curriculum and the approach to making this change was made by the county curriculum staff in co-operation with the school principals. This analysis suggested that the usual efforts—institutes, lectures, required attendance of college classes—had not over a period of years produced much curriculum improvement and did not seem promising for making changes in the structure of curriculum. Furthermore, the teachers in various districts tended to regard the county as authoritarian and it was difficult to kindle their initiative for curriculum improvement.

So, the beginning of the study was largely concerned with the identification and analysis of teachers’ problems in the field of social studies. The teachers, after they had identified mismatches in the curricula they were using with their expectations for them, were asked to develop their own teaching/learning units. As the teachers’ expertise was not sufficient for curriculum development, seminars and consultancy sessions were organized. The members of the research team primarily provided this kind of in-service training for co-operating teachers. Consequently, the research programme was aimed at the re-education of the whole staff and at producing pilot models of curriculum development and teaching.

The main purpose of the study was to provide a flexible model of curriculum renewal, based on conjoint efforts of practising teachers and educational administrators responsible for school curricula. It is important to mention that many ideas underlying Taba’s curriculum model, such as the notion of a ‘spiral’ curriculum, inductive teaching strategies for the development of concepts, generalizations and applications; organization of content on three levels—key ideas, organizational ideas and facts—and her general strategy for developing thinking through the social studies curriculum significantly influenced curriculum developers during the 1960s and early 1970s. Many general principles and ideas of curriculum design developed by Hilda Taba belong to the foundations of modern curriculum theories, and are frequently referred to by other authors.

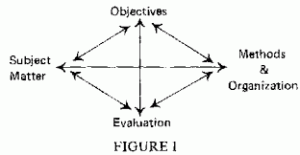

This approach allowed Hilda Taba to relate specific teaching/learning strategies to each category of objectives. In this sense, her classification of educational objectives. The selection and organization of content implements only one of the four areas of objectives—that of knowledge. The selection of content does not develop the techniques and skills for thinking, change patterns of attitudes and feelings, or produce academic and social skills. These objectives only can be achieved by the way in which the learning experiences are planned and conducted in the classroom. Achievement of three of the four categories of objectives depends on the nature of learning experiences rather than on the content .

Hilda Taba died unexpectedly on 6 July 1967, at the peak of her academic capabilities and power.

Taba’s – theoretical rationale on curriculum development

A preliminary, and incomplete, analysis of her scientific heritage suggests at least four principles that seem to govern her vision of curriculum theory and curriculum development:

Social processes, including the socialization of human beings, are not linear, and they cannot be modelled through linear planning. In other words, learning and development of personality cannot be considered as one-way processes of establishing educational aims and deriving specific objectives from an ideal of education proclaimed or imagined by some authority.

Social institutions, among them school curricula and programmes, are more likely to be effectively rearranged if, instead of the common way of administrative reorganization— from top to bottom—a well-founded and co-ordinate system of development from bottom to top can be used.

The development of new curricula and programmes is more effective if it is based on the principles of democratic guidance and on the well-founded distribution of work. The emphasis is on the partnership based on competence, and not on administration.

The renovation of curricula and programmes is not a short-term effort but a long process, lasting for years.

The principle of considering social processes as non-linear is the most important one, and it probably governs all of Hilda Taba’s educational work. Applying the principle to curriculum design, this means that it is unreal and impossible to set up rigid general goals of education from which more specified objectives would be derived for a concrete plan. The general goals are also subject to modification in order to become adapted to the real circumstances, whereby they are dependent more or less on the content and character of the educational step planned.

The second principle of the efficiency of the bottom-up approach suggests the most convenient way to help individuals and human social organizations to accept and to adapt to new situations and ideas. The expected changes in the individual or social consciousness will take place only if individuals or groups, under pressure to introduce these changes, conserve or acquire the ability to learn. So, the changes and learning underlying it take place more easily, and meet less opposition if they are not imposed by the central institutions but are initiated in the periphery, and gradually spread all over the structure.

The third and fourth principles underline the necessity for the democratic guidance of curriculum development and the long-term nature of this process, and are essentially derived from the first two principles.

Hilda Taba Model of Curriculum Development

Curriculum is the heart of schooling. The difficulty, however, is that not everyone agrees what curriculum is or what is involved in curriculum development. One way of developing a curriculum plan is through modeling. Models are essentially patterns that serve as guidelines to action. Unfortunately, the term model as used in the education profession often lacks precision. A model may, propose a solution to a piece of a problem, attempt to solve to a specific problem, create or replicate a pattern on a grander scale. Models can be found for almost every form of educational activity.

Curriculum models are just as instructional designs. They bring competency in educational process and teaching-learning. They are the best ways to proceed in formulating theories of teaching training; instruction should begin with what is known about leaning and instruction. Teaching models are the basis of teaching theories. The curriculum models are very useful for teachers for planning and agenizing educational process. They can use models in the traction of curriculum preparing an outline for guiding students’ activity and developing instructional procedure for realizing objectives. Curriculum models are very close to models of teaching.

Hilda Taba the Curriculum theorist, curriculum reformer, and teacher educator, contributed to the theoretical and pedagogical foundations of concept development and critical thinking in social studies curriculum and helped to lay the foundations of education for diverse student populations.

Hilda Taba more focused on a model of how to develop the curriculum as a process improvement and curriculum improvement. Hilda Taba believed that the curriculum should be designed by the teachers rather than handed down by higher authority. Further, she felt that teachers should begin the process by creating specific teaching-learning units for their students in their schools rather than by engaging initially in creating a general curriculum design. Hilda Taba advocated an inductive approach to curriculum development. In the inductive approach, curriculum workers start with the specifics and build up to a general design as opposed to the more traditional deductive approach of starting with the general design and working down to the specifics,

Hilda Taba developed Inductive Teaching Model which backbone to social studies curriculum.

Focus. Its main focus is to develop the mental abilities and lay emphasis upon concept formation. It involves cognitive tasks in concept formation.

Syntax. The teaching is organized in nine phases. The first three phases are concerned with the concept formation involving enumeration, grouping and labeling categories. The second three phases are related to the interpretation of data by identifying relationship, explaining relationship and drawing inferences. The last three .phases arc concerned with an application of principles by hypothesizing, explaining and verifying the hypothesis.

Social System. In the all nine phases, the classroom climate is conducive to learning and cooperative. A good deal of freedom should be given for pupil-activities. The teacher is usually the controller and initiator of information. Teaching activities arc arranged in a logical sequence in advance.

Support System. The teacher should help the students in dealing with the more complex data and information. He should encourage them in processing the data, basically designed to develop thinking capacity. A particular mental and cognitive task requires specific strategy to improve thinking.

Classroom Application. Taba designed his model to create inductive thinking among learners. It helps to organize social studies curriculum so that cognitive process may be facilitated. The learning experiences are the basis of information to arrange the content in an effective sequence. The first three phases arc useful in dealing with elementary classes, while the last three phases are useful for higher classes especially for science and language curriculum.

Evaluation. Hilda Taba has developed teaching model as well as curriculum model. His curriculum model is based on the evaluation concept.That In designing the outline of the curriculum, evaluation plays significant role.

Hilda Taba’s four steps of curriculum construction:

1. Identification of objectives.

2. Evidence for teaching-learning operation.

3. Evidences of factors affecting learning.

4. Evidences of pupil behavior pertaining objectives

Step1. The curriculum is a evaluated in the light of educational objectives identified for preparing learning experiences. These objectives include-cognitive, affective, psycho-motor creativity and perceptions, The evidences are collected for the identification of the objectives

Comprehensive Evaluation Curriculum Models [Hilda Taba]

Step 2. Appropriate teaching method, teaching technique and audio-visual aids are used for generating appropriate learning situations, so that desirable objectives can be achieved. Evidences are collected for the learning experiences.

Step 3. The evidences are collected for teaching-learning operations such as motivation reinforcement which help in learning of the student. This influences the learning exercise. Audio-visual aids makes learning experiences interesting. The students do not memorize the content.

Step 4. The utility of the curriculum is evaluated on the basis of changes of behavior .’These are evidences for realizing the education objectives. The examination system is objectives-centred. It is both qualitative and quantitative. An attempt is made to assess the total change of behavior.

Stages of Curriculum Development

Stage 1. Deciding the kinds of evaluation data needed.

Stage 2. Selecting or constructing the needed instruments and procedure.

Stage 3. Analysing and interpreting the data to develop the hypothesis regarding needed change.

Stage 4. Converting hypothesis into action.

Hilda Taba curriculum model is based on the evaluation approach of B.S.Bloom designed for examination reform. Evidences collected in different stages are used to diagnose the weaknesses of T curriculum. These evidences are further used for formulating hypothesis. The structure of the curriculum is mollified on the basis ol verification of the hypothesis. Thus, an empirical approach is used for the curriculum development. The hypothesis indicate the type of modification needed in curriculum development.

The above steps and stages are used in sequences. This model of curriculum is highly empirical. The modification is done on the basis of evidences.

In short Taba advocated for a flexible model of curriculum renewal based on joint efforts of practicing teachers, educational administrators and researchers. Her curriculum model covers many of the critical topics, from aims and goals of education, the selection of the content, the process of organizing learning and school development, and evaluation at different levels. Several general principles and ideas of curriculum design developed by Hilda Taba belong to the foundations of modern curriculum theories.

Probably the most characteristic feature of Hilda Taba’s educational thinking was the ability to see the forest for the trees, pointing to her capability to discriminate between the essential and the non-essential or the important and the unimportant. She was never misled by the outside lustre of an idea even when facing the most advanced educational innovations of the day, and she always scrutinized them for their educational purpose or value.

REFERANCES

Blenkin, G. M. et al (1992) Change and the Curriculu,, London: Paul Chapman.

Bobbitt, F. (1918) The Curriculum, Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Bobbitt, F. (1928) How to Make a Curriculum, Boston: Houghton MifflinCornbleth, C. (1990) Curriculum in Context, Basingstoke: Falmer Press.

Curzon, L. B. (1985) Teaching in Further Education. An outline of principles and practice 3e, London: Cassell.

Dewey, J. (1902) The Child and the Curriculum, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1938) Experience and Education, New York: Macmillan.

Jeffs, T. J. and Smith, M. K. (1999) Informal Education. Conversation, democracy and learning, Ticknall: Education Now.

Kelly, A. V. (1983; 1999) The Curriculum. Theory and practice 4e, London: Paul Chapman.

Stenhouse, L. (1975) An introduction to Curriculum Research and Development, London: Heineman.

Taba, H. (1962) Curriculum Development: Theory and practice, New York: Harcourt Brace and World.

Tyler, R. W. (1949) Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.