FAMILY HISTORY- AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF NETA JI SUBHAS CHANDRA BOSE

Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

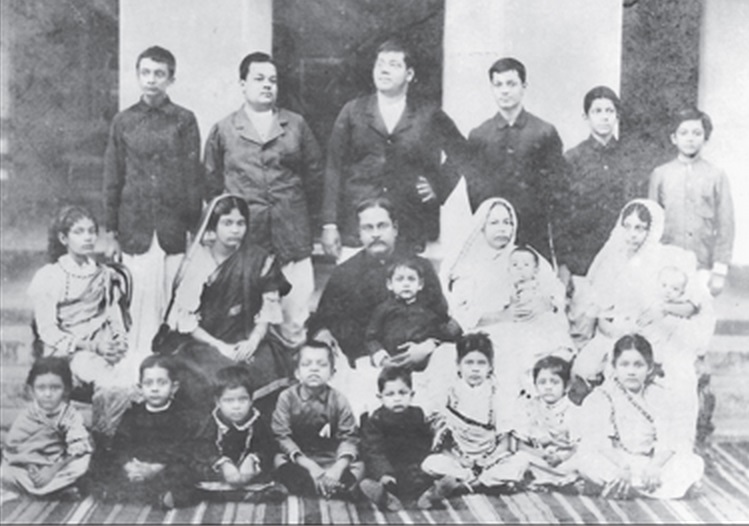

Subhash Boss standing extreme right with his large family , Cuttack, India 1905.

Subhash Boss standing extreme right with his large family , Cuttack, India 1905.

The history of our family can be traced back for about 27 generations. The Boses (The original form in Sanskrit is Basu or rather Vasu. In common parlunce in Bengali, Vasu has become Bose. ) are Kayastha ( The Kayasthas claim to be none other than Kshatriyas (i.e., warrior caste) in origin. According to popular usage, the Kayasthas are classified among the (so—called) higher castes. ) by caste. The founder of the Dakshin-Rarhi (Dakshin-Rarhi probably means ‘South-Bengal ) clan of the Boses was one Dasaratha Bose, who had two sons, Krishna and Parama. Parama went over to East Bengal and settled there, while Krishna lived in West Bengal. One of the great—great-grandsons of Dasaratha was Mukti Bose, who resided at Mahinagar, a village about 14 miles to the south of Calcutta, wl1ence the family is now known as the Boses of Mahinagar. (From Calcutta Mahinagar can be reached via Chingripota, a station on the Diamond Harbour Railway line)

Eleventh in descent from Dasaratha was Mahipati, a man of outstanding ability and intelligence. He attracted the attention of the then King of Bengal, who appointed him as Minister for Finance and War. In appreciation of his services, the King, who was Muslim by religion, conferred on him the title of ‘Subuddhi Khan As was the prevailing custom, Mahipati was also given a ‘jaigir’ (landed property) as a mark of royal favour and the village of Subuddhipur, not far from Mahinagar, was probably his jaigir. Of Mahipati’s ten sons, Ishan Khan, who was the fourth, rose to eminence and maintained his father’s position at the Royal Court. Ishan Khan had three sons, all of whom received titles from the King. ‘The second son, Gopinath Bose, possessed extraordinary ability and prowess and was appointed Finance Minister and Naval Commander by the then King, Sultan Hossain Shah (1493-1519). He was rewarded with the title of Purandar Khan and a jaigir, now known as Purandarpur, not far from his native village of Mahinagar. In Purandarpur there is a tank called “Khan Pukur” (or Khan’s Tank) which is a relic of a one-mile long tank excavated by Purandar Khan. The village of Malancha near Mahinagar has grown on the site of Purandar’s Garden.

In those days the Hooghly flowed in the vicinity of Mahinagar and it is said that Purandar used to travel by boat to and from Gaud, the then capital of Bengal. He built up a powerful navy which defended the kingdom from external attack and was its commander.

Purandar also made his mark as a social reformer. Before his time, according to the prevailing Ballali custom, the two wings of the Kayasthas Kulin (who were the elite, viz., the Boses, the Ghoses, and the Mitras) and Moulik (the Dutts, the Deys, the Roys etc.) did not, as a rule, intermarry. ( Intercaste marriage which has been going on for the last 50 years or more has considerably slackencd existing caste rules. the Purandar’s time this move was regarded as revolutionary. The outstanding position he had in social and public life enabled him to put through this measure of reform. It is said that he invited over 100,000 Kayasthas to his village to have the new code adopted by them. ‘Khan’s Pukur’ was excavated on this occasion to supply pure drinking water to this vast assembly .) Purandar laid down a new custom to the effect that only the eldest issue of a Kulin need marry into a Kulin family, while the others could marry Mouliks. This custom, which has been generally followed till the present day, saved the Kayasthas from impending disaster the fruit of excessive inbreeding. Purandar was also a man of letters. His name figures among the composers of Padabali, the devotional songs of the Vaishnavas.

Evidence is afforded by several Bengali poems, like Kavirama’s ‘Ray1nangal’, that as late as 200 years ago, the Hooghly (called in Bengali Ganga) flowed by Mahinagar and the neighbouring villages. (Even now, all tanks in the former bed of the ‘Ganga’ are also called ‘Ganga’ by courtesy, e.g., Bose’s Ganga, meaning thereby Bose’s tank.) The shifting of the river-bed struck a death blow at the health and prosperity of these villages. Disturbance of the drainage of the countryside was followed by epidemics, which in turn forced a large section of the population to migrate to other places. One branch of the Bose family the direct descendants of Purandar Khan-moved to the adjoining village of Kodalia.

After a period of comparative silence, this neighbourhood, containing the villages of Kodalia, Chingripota, Harinavi, Malancha, Rajpur, etc. leapt into activity once again. During the early decades of the nineteenth century there was a remarkable cultural upheaval which continued till the end of the century when once again the countryside was devastated by epidemics malaria carrying off the palm this time. Today one has only to walk through these desolated villages and observe huge mansions overgrown with wild creepers standing in a dilapidated condition, in order to realise the degree of prosperity and culture which the neighbourhood must have enjoyed in the not distant past. The scholars who appeared here about a century ago were mostly men learned in the ancient lore of India, but they were not obscurantists by any means. Some of these Pundits were preceptors of the Brahmo Samaj, then a revolutionary body from the spcio-cultural point of view, while others were editors of secular journals printed in Bengali which were playing an important part in creating a new Bengali literature and in influencing contemporary public affairs.

Pundit Ananda Chandra Vedantavagecsh was the editor of Tattwabodhini Patrika, an influential journal of those days and also a preceptor of the Brahmo Samaj. Pundit Dwarakanath Vidyabhusan was the editor of Som Praksh, probably the first weekly journal to be printed in the Bengali language. One of his nephews was Pundit Shivanath Shastri, one of the outstanding personalities of the Brahmo Samaj. Bharat Chandra Shiromani was one of the authorities in Hindu Law, especially in the Bengal school of Hindu Law called ‘Dayabhag’. Among the artists could be named Kalikumar Chakravarti, a distinguished painter, and among musicians, Aghor Chakravarti and Kaliprasanna Bose. During the last few decades the locality has played an important part in the nationalist movement. Influential Congressmen like Harikumar Chakravarti and Satkari Bannerji (who died in the Deoli Detention Camp in 1936) hail from this quarter, and no less a man than Comrade M. N. Roy, of international fame, was born there.

To come back to our story, the Boses who migrated to Kodalia must have been living there for at least ten generations, for their genealogical tree is available} My father was the thirteenth in descent from Purandar Khan and twenty sixth from Dasaratha Bose. My grandfather Haranath had four sons, Jadunath, Kedarnath, Devendranath, and Janakinath my father.

Though by tradition our family was Shakta, ( The Hindus of Bengal were, broadly speaking, divided into two schools or sects, Shakta and Vaishnava. Shaktas preierred to worship God as Power or Energy in the form of Mother. The Vaishnavas wor¬shipped God as Love in the form of father and protector. The difference became manifest at the time of initiation, the ‘mantra’ or ‘holy word’ which a Shakta received from his ‘guru’, or preceptor, being different from what a Vaishnava received from his guru. It was customary for a family to follow a particular tradition for generations, though there was nothing to prevent a change from one sect to the other permanently.) Haranath was a pious and devoted Vaishnava. The Vaishnavas being generally more non—violent in temperament, Haranath stopped the practice of goat-sacrifice at the annual Durga Pooja (worship of God as Divine Energy in the form of mother) which used to be celebrated with great pomp every year Durga Poojah being the most important festival of the Hindus of Bengal. This innovation has been honoured till the present day, though another branch of the Bose family living in the same village still adheres to goat-sacrifice at the annual Poojah.

Haranath’s four sons migrated to different places in search of a career. The eldest Jadunath who worked in the Imperial Secretariat had to spend a good portion of his time in Simla. The second, Kedarnath, moved to Calcutta. The third, Devendranath, who joined the educational service of the Government and rose to the rank of Principal, had to move about from place to place and after retirement settled down in Calcutta. My father was born on the 28th May, 1860 and my mother in 1869 After passing the Matriculation (then called Entrance) Examination from the Albert School, Calcutta, he studied for some time at the St. Xavier’s College and the General Assembly’s Institution (now called Scottish Church College). He then went to Cuttack and graduated from the Ravenshaw College. He returned to Calcutta to take his law degree and during this period came into close contact with the prominent personalities of the Brahmo Samaj, Brahmanand Keshav Chandra Sen, his brother Krishna Vihari Sen, and Umesh Chandra Dutt, Principal of the City College. He worked for a time as Lecturer in the Albert College, of which Krishna Vihari Sen was the Rector. In 1885 he went to Cuttack and joined the bar. The year 1901 saw him as the first non-official elected Chairman of the Cuttack Municipality. By 1905 he became Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor. In 1912 he became a member of the Bengal Legislative Council and received the title of Rai Bahadur. In 1917, following some differences with the District Magistrate, he resigned the post of Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor and thirteen years later, in 1930, he gave up the title of Rai Bahadur as a protest against the repressive policy of the Government.

Besides being connected with public bodies like the Municipality and District Board, he took an active part in educational and social institutions like the Victoria School and Cuttack Union Club. He had extensive charities, and poor students came in for a regular share of them. Though the major portion of his charities went to Orissa, he did not forget his ancestral village, where he founded a charitable dispensary and library, named after l1is mother and father respectively. He was a regular visitor at the annual session of the Indian National Congress but he did not actively participate in politics, though he was a consistent supporter of Swadeshi (home-industries) After the commencement of the Noncooperation Movement in 1921, he interested himself in the constructive activities of the Congress, Khadi (Khadi or Khaddar is hand-spun and hand-woven cloth) and national education. He was all along of a religious bent of mind and received initiation twice, his first guru being a Shakta and the second a Vaishnava. For years he was the President of the local Theosophical Lodge. He had always a soft spot for the poorest of the poor and before his death he made provisions for his old servants and other dependants.

As mentioned in the first chapter, my mother belonged to the family of the Dutts of Hatkhola, a northern quarter of Calcutta. In the early days of British rule, the Dutts(The original Sanskrit form of this word is “Datta” or “Dutta”. “Dutt” is an anglicised abbreviation of this word.) were one of those families in Calcutta who attained a great deal of prominence by virtue of their wealth and their ability to adapt themselves to the new political order. As a consequence, they played a role among the neo-aristocracy of the day. My mother’s grandfather, Kashi Nath Dutt, broke away from the family and moved to Baranagore, a small town about six miles to the north of Calcutta, built a palatial house for himself and settled down there. He was a very well-educated man, a voracious reader and a friend of the students. He held a high administrative post in the firm of Messrs Jardine, Skinner & Co., a British firm doing business in Calcutta. Both my mother’s father, Ganganarayan Dutt, and grandfather had a reputation for being wise in selecting their sons-in-law. They were thereby able to make alliances with the leading families among the Calcutta aristocracy of the day. One of Kashi Nath Dutt’s sons-in-law was Sir Romesh Chandra Mitter, ( This is the same as Mitra. Sir Romesh had three sons-the late Manmatha Nath, Sir Benode, and Sir Pravas Mitter. The late Sir B. C. Mitter was Advocate-General of Bengal and later on, member of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Sir Pravas Mitter was member of the Executive Council of the Governor of Bengal.) who was the first Indian to be acting Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court. Another was Rai Bahadur Hari Vallabh Bose who had migrated to Cuttack before my father and as a lawyer had won a unique position for himself throughout the whole of Orissa.

It is said of my maternal grandfather, Ganganarayan Dutt, that before he agreed to give my mother in marriage to my father, he put the latter through an examination and satisfied himself as to his intellectual ability. My mother was the eldest daughter. Her younger sisters were married successively to (the late) Barada Ch. Mitra, C.S., District and Sessions Judge, Mr Upendra Nath Bose of Benares City, (the late) Chandra Nath Ghose, Subordinate Judge and (the late) Dr J. N. Bose, younger brother of the late Rai Bahadur Chuni Lal Bose of Calcutta.

From the point of view of eugenics it is interesting to note that, on my father’s side, large families were the exception and not the rule. On my mother’s side, the contrary seems to have been the ease .` Thus my maternal grandfather had nine sons and six daughters . Among his children, the daughters generally had large families—including my mother but not the sons. My parents had eight sons and six daughters,“ of whom nine, seven sons and two daughters are still living.

Among my sisters and brothers, some—but not the majority have as many as eight or nine children, but it is not possible to say that the sisters are more prolific than the brothers or vice versa. It would be interesting to know if in a particular family the prolific strain adheres to one sex more than to the other. Perhaps eugenists could answer the question.

REFERANCE-

N E T A J I’ S – LIFE and WRITINGS – PART ONE- AN INDIAN PILGRIM OR AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SUBHAS CHANDRA BOSE

Calcutta 23rd January 1948