The recent transition to the information age has focused attention on the processes of problem solving and decision making and their improvement). In fact the strategies used in these processes to be a primary outcome of modern education. Although there is increasing agreement regarding the prescriptive steps to be used in problem solving, there is less consensus on specific techniques to be employed at each step in the problem-solving/decision-making process.

The recent transition to the information age has focused attention on the processes of problem solving and decision making and their improvement). In fact the strategies used in these processes to be a primary outcome of modern education. Although there is increasing agreement regarding the prescriptive steps to be used in problem solving, there is less consensus on specific techniques to be employed at each step in the problem-solving/decision-making process.

Problem-Solving and Decision-Making Process

A problem is any situation where you have an opportunity to make a difference, to make things better; and problem solving is( converting an actual current situation ) into a desired future situation Whenever you are thinking creatively and critically about ways to increase the quality of life or avoid a decrease in quality you are actively involved in problem solving.

Problem solving is a process in which we perceive and resolve a gap between a present situation and a desired goal, with the path to the goal blocked by known or unknown obstacles. In general, the situation is one not previously encountered, or where at least a specific solution from past experiences is not known.

Phases in models of problem solving and decision making

1) An Input phase in which a problem is perceived and an attempt is made to understand the situation or problem;

2) A Processing phase in which alternatives are generated and evaluated and a solution is selected;

3) An Output phase which includes planning for and implementing the solution; and

4) A Review phase in which the solution is evaluated and modifications are made

Each phase of the process includes specific steps to be completed before moving to the next phase.

.Problem-Solving Techniques

It is necessary to identify specific techniques of attending to individual differences. Fortunately, a variety of problem-solving techniques have been identified to accommodate individual preferences

Techniques focus more on logic and critical thinking, especially within the context of applying the scientific approach:

A. Network analysis–a systems approach to project planning and mangement where relationships among activities, events, resources, and timelines are developed and charted. Specific examples include Program Evaluation and Review Technique and Critical Path I. Plus-Minus-Interesting (PMI)–considering the positive, negative, and interesting or thought-provoking aspects of an idea or alternative using a balance sheet grid where plus and minus refer to criteria identified in the second step of the problem-solving process J. Task analysis–the consideration of skills and knowledge required to learn or perform a specific task.

B.Thinking aloud–the process of verbalizing about a problem and its solution while a partner listens in detail for errors in thinking or understanding

C.Inductive/deductive reasoning–the systematic and logical development of rules or concepts from specific instances or the identification of cases based on a general principle or proposition using the generalization and

D. Challenging assumptions–the direct confrontation of ideas, opinions, or attitudes that have previously been taken for granted

ECategorizing/classifying–the process of identifying and selecting rules to group objects, events, ideas, people, etc

F. Analysis–the identification of the components of a situation and consideration of the relationships among the parts

G. Backwards planning–a goal selection process where mid-range and short-term conditions necessary to obtain the goal are identified this technique is related to the more general technique of means-ends analysis

H.. Evaluating/judging–comparison to a standard and making a qualitative or quantitative judgment of value or worth

Techniques focused on creative, lateral, or divergent thinking

A. Synthesizing–combining parts or elements into a new and original pattern J. Taking another’s perspective–deliberately taking another person’s point of view

B. Relaxation–systematically relaxing all muscles while repeating a personally meaningful focus word or phrase a specific example of the more general technique called “suspenders” by Wonder and Donovan (1984);

C. Imaging/visualization–producing mental pictures of the total problem or specific parts of the problem

D. Brainstorming–attempting to spontaneously generate as many ideas on a subject as possible; ideas are not critiqued during the brainstorming process; participants are encouraged to form new ideas from ideas already stated

E. Values clarification–using techniques such as role-playing, simulations, self-analysis exercises, and structured controversy to gain a greater understanding of attitudes and beliefs that individuals hold important

F. Outcome psychodrama–enacting a scenario of alternatives or solutions through role playing

G. Outrageous provocation–making a statement that is known to be absolutely incorrect (e.g., the brain is made of charcoal) and then considering it; used as a bridge to a new idea also called “insideouts”

H. Values clarification–using techniques such as role-playing, simulations, self-analysis exercises, and structured controversy to gain a greater understanding of attitudes and beliefs that individuals hold important

I. Overload–considering a large number of facts and details until the logic part of the brain becomes overwhelmed and begins looking for patterns (Wonder & Donovan, 1984); can also be generated by immersion in aesthetic experiences (Brookfield, 1987), sensitivity training (Lakin, 1972), or similar experiences;

J. Random word technique–selecting a word randomly from the dictionary and juxtaposing it with problem statement, then brainstorming about possible relationships

K. Incubation--putting aside the problem and doing something else to allow the mind to unconsciously consider the problem

.Integrating Techniques into the Problem-Solving Process

The problem-solving techniques discussed above are most powerful when combined to activate both the logical/rational and intuitive/creative parts of the brain. The following narrative will provide an example of how these techniques can be used at specific points in the problem-solving process to address important individual differences. The techniques will be presented within the context of a group problem-solving situation but are equally applicable to an individual situation. The terms in parentheses refer to personality dimensions to which the technique would appeal.

The Input Phase

The goal of the Input phase is to gain a clearer understanding of the problem or situation.

The first step is to identify the problem(s) and state it(them) clearly and concisely. Identifying the problem means describing as precisely as possible the gap between one’s perception of present circumstances and what one would like to happen. Problem identification is vital to communicate to one’s self and others the focus of the problem-solving/decision-making process. Arnold (1978) identified four types of gaps:

1) something is wrong and needs to be corrected;

2) something is threatening and needs to be prevented;

3) something is inviting and needs to be accepted; and

4) something is missing and needs to be provided.

Tunnel vision (stating the problem too narrowly) represents the major difficulty in problem identification as it leads to artificially restricting the search for alternatives.

Brainstorming is an excellent technique to begin the problem-solving process. Individually, participants quickly write possible solutions (introversion, perception), share these alternatives as a group in a non-judgmental fashion, and continue to brainstorm (extraversion, perception). Participants then classify, categorize, and prioritize problems, forming a hierarchy of the most important to the least important (intuition, thinking).

The second step of the Input phase is to state the criteria that will be used to evaluate possible alternatives to the problem as well as the effectiveness of selected solutions.

During this step it is important to state any identified boundaries of acceptable alternatives, important values or feelings to be considered, or results that should be avoided. In addition, criteria should be categorized as either essential for a successful solution or merely desired.

Brainstorming can also be used during this second step. Participants quickly write possible criteria for use in evaluating alternatives (introversion, perception). These factors generally fall into the following categories:

1) important personal values, attitudes, and feelings to be considered (sensing, feeling);

2) important values, attitudes, and feelings to be considered in context of the work group, organization, community, society, etc. (extraversion, intuition, feeling);

3) practical factors that relate to how an alternative should work (sensing, thinking); and

4) factors that logically flow from the statement of the problem, relevant facts, or how the solution should fit into the larger context (intuition, thinking).

Values clarification techniques can be very useful in generating criteria related to values, feelings, and attitudes. Role-playing and simulations are especially appreciated by those generally take a more practical approach to problem solving. Self-analysis exercises and structured controversy are more likely to appeal to those who focus on principles and abstractions. In addition, the use of both deductive and inductive reasoning can be important in generating criteria. For example, logically generating criteria from the problem statement would use deductive reasoning, whereas combining several different values or feelings to form criteria would use inductive reasoning.

After criteria are generated they are then shared in a non-judgmental manner using procedures suggested in values clarification strategies, Important criteria are placed into different categories, and a preliminary selection is made. Selected criteria are then evaluated in terms of their reasonableness given the problem statement).

The third step is to gather information or facts relevant to solving the problem or making a decision. This step is critical for understanding the initial conditions and for further clarification of the perceived gap. Most researchers believe that the quality of facts is more important than the quantity. In fact, noted that collecting too much information can actually confuse the situation rather than clarify it.

The brainstorming technique could again be used in this step. As done previously, participants quickly write those facts they believe to be important These facts are classified and categorized, and relationships and meaningfulness are established .The techniques of imaging and overload can be used to establish patterns and relationships among the facts. The facts are analyzed in terms of the problem statement and criteria, and non-pertinent facts are eliminated). The remaining facts and associated patterns are then prioritized and additional facts collected as necessary (thinking, perceiving).

The Processing Phase

In the Processing phase the task is to develop, evaluate, and select alternatives and solutions that can solve the problem. The first step in this phase is to develop alternatives or possible solutions. Most researchers focus on the need to create alternatives over the entire range of acceptable options as identified in the previous phase .This generation should be free, open, and unconcerned about feasibility.

Here, brainstorming is a technique that can be used first. Participants quickly write alternatives using the rules of brainstorming then share the results in a non-judgmental fashion and develop additional alternatives A number of the techniques mentioned above such as challenging assumptions, imaging, outcome psychodrama, outrageous provocation, the random word technique, and taking another’s perspective can be used at this point to generate more creative alternatives. Those alternatives obviously unworthy of further consideration are eliminated It is possible to categorize or classify alternatives and consider them as a group, If the person or group is dissatisfied with the quantity or quality of the alternatives under consideration, a brief use of the progressive relaxation technique may be beneficial as well as the application of another, previously unused, creative technique. If dissatisfaction still remains, putting aside the problem (incubation) may be helpful.

The next step is to evaluate the generated alternatives vis-a-vis the stated criteria. Advantages, disadvantages, and interesting aspects for each alternative are written individually then shared and discussed as a group. After discarding alternatives that are clearly outside the bounds of the previously stated criteria, both advantages and disadvantages should be considered in more detail. An analysis of relationships among alternatives should be completed and consideration should be given to the relative importance of advantages and disadvantages. Only those alternatives the majority considers relevant and correct are considered further.

The third step of the processing phase is to develop a solution that will successfully solve the problem. For relatively simple problems, one alternative may be obviously superior. However, in complex situations several alternatives may likely be combined to form a more effective solution A major advantage of this process is that if previous steps have been done well then choosing a solution is less complicated.

Before leaving this phase it is important to diagnose possible problems with the solution and implications of these problems. When developing a solution it is important to consider the worst that can happen if the solution is implemented

The Output Phase

During this phase a plan is developed and the solution actually implemented. The plan must be sufficiently detailed to allow for successful implementation, and methods of evaluation must be considered and developed. When developing a plan, the major phases of implementation are first considered ,and then steps necessary for each phase are generated. It is often helpful to construct a timeline and make a diagram of the most important steps in the implementation using a technique such as network analysis. Backwards planning and task analysis are also useful techniques at this point. The plan is then implemented as carefully and as completely as possible.

The Review Phase

The next step, should be an ongoing process. Some determination as to completeness of implementation needs to be considered prior to evaluating effectiveness. This step is often omitted and is one reason why the problem-solving/decision-making process sometimes fails: However, if the solution is not implemented then evaluation of effectiveness is not likely to be valid.

The second step of this phase is evaluating the effectiveness of the solution. It is particularly important to evaluate outcomes in light of the problem statement generated at the beginning of the process. Affective, cognitive, and psycho-motor outcomes should be considered, especially if they have been identified as important criteria. The solution should be judged as to its efficiency, its impact on the people involved and the extent to which it is valued by the participants .

The final step in the process is modifying the solution in ways suggested by the evaluation process. Issues identified in terms of both efficiency and effectiveness of implementation should be addressed.

INSTRUCTIONAL PROCEDURE FOR PROBLEM- SOLVING IN EDUCATION

Like any other systematic analysis the process of development of problem solving too can be analyzed in the following manner.

|

What ought to be aspect |

|

How aspect |

|

Why aspect |

|

What aspect |

What aspect deals with the nature of the problem.

Why aspect deals with reasoning based on the necessity and advantage of acquiring any specific solution i.e. the importance and justification of finding solution of the problem..

How aspect is related with the methodology of acqusition of any particular solution.

What ought to be aspect is related with the evaluation of the final output for the purpose of feedback.

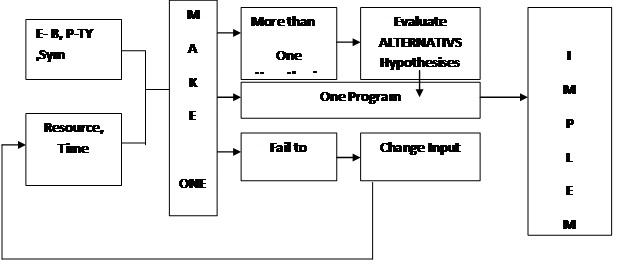

The following analytical presentation can provide birds’ eye view of the entire procedure-

HERE-

E-B= Entering Behavior, P-Ty=Personality Type. Sym= Symptoms of problem

On the basis of the above procedure the following steps are suggested-

Step-1- Analyze the Problem -

Our first teaching function is to do a task analysis of the Problem one plan to solve.

Step-2- Assesses the entering behavior of the students-

- The second teaching function is to determine the adequacy of the student’s preparation for solving the problem

- Step-3- Arrange for training in the component units, ability- This step has two purposes: It provides the student with the opportunity to learn missing links or component of problems or to develop the prerequisite abilities and to provide the student with the opportunity to learn the the inherent factors. So well that he can focus his attention on the new aspects of the complex task he is learning.

- Step-4- Describe and demonstrate the probable final solution to the student- This step makes the actual teaching of the overall task. Here the student usually listens to instructions observe demonstrations, tries out different components of solution available and then somehow starts solving the problem..

- Step-5- Provide for the three basic learning conditions- In teaching systematic solution, it is advisable to combine the three learning conditions- contiguity, practice and feedback into a single step because they usually provide them concurrently rather than sequentially.

Advantages

The advantages of the process can be considered in three major categories: and individual. General ,and organizational,

Individual. One of the primary advantage to individuals in using this process is that the strengths and weaknesses of the individual can be identified and used or compensated for when making a decision. Everyone has strong and weak points that result from preferences in how a problem is viewed or considered. Careful selection and application of techniques reviewed increase the likelihood that individuals will enhance their strengths and attend to issues they would otherwise omit or attend to less well.

When participating in the problem-solving process in a group, two additional advantages occur. First, individuals can learn to value alternative viewpoints or preferences by considering differences in others as strengths rather than as “wrong” or of less value. However, all preferences and a variety of techniques must be used if the best solutions are to be developed and implemented.

Additionally, the development of an individual’s decision-making powers can be enhanced by advancing through the process with others in a group situation. have demonstrated that verbalizing one’s thinking process while someone else listens and critiques that process / technique is one of the most valuable ways to improve problem solving and decision making. When individuals are active and participate in a group-based, problem-solving process, it can lead to the development of the temprament required to make better independent decisions.

General. One of the primary advantage is that the process provides for the generation of both objective and subjective criteria used to select and evaluate alternatives. That is, reason and logic are balanced by creativity and divergence throughout the process It is demonstrated that when individuals used both types of techniques they were more successful in their problem solving.. Additionally, the process has a built-in step to consider what could go wrong if particular solutions are selected

A second general advantage. of using this process is that it is an effective way of managing change. Because rapid and unpredictable change is the norm today, it is important that sufficient resources be available to manage it. In addition, the process can be used by individuals and organizations to solve a wide variety of problems. Since there is continuous diversity in the types of problems to be solved, it is important to have a flexible, process to resolve them.. While it may be impossible to have a single process that is applicable to all problems or decisions by all individuals, it is important to have a flexible, process that individuals believe fits with their unique styles and that can be used to capitalize on strengths and support weaknesses.

Work group or organization. One of the primary advantage of using this process is that it allows individuals within the group to understand the problem thoroughly before considering alternatives. Too often, problem-solving discussions focus on the debate of preselected alternatives. At the outset of the discussion .participants select positions as to which alternative is better. The result is a separation into camps of winners and losers. Use of this process takes energy normally spent on arguing for a specific solution and use that energy into a collective search for an acceptable solution.

A related advantage is that a thorough discussion prior to considering alternatives can actually make problem solving less complicated and successful results more likely to be achieved. Quite often group discussion is not about solutions, but about assumptions of facts, criteria, and important values that remain unstated throughout the deliberation. By clearly stating these before alternatives/solutions are discussed, the actual selection of alternatives is often easier. Frequently a lack of careful analysis by groups attempting to solve a problem leads to selecting a solution on some criteria other than “does it solve the problem.” Sometimes a situation of “group think” occurs where one alternative is presented, and everyone simply agrees that it is best without critical analysis. This can lead the organization to make decisions based on power relationships (the boss likes this one), on affiliations (Mr X is my friend, so I’ll support him), or on some basis other than achievement of goals.

Finally, use of a problem-solving process enhances the development of unity within the work group or organization. If everyone is using the same process of problem solving, then unity or consensus is much easier to achieve. Unified action generally produces better results than no unified action. If the selected solution is incorrect, then problems can be identified quickly and corrections can be made. On the other hand, if all participants are not working toward a common goal or if some members are actually trying to work against group goals, then energy that should be focused on solving the problem is dissipated; the proper solution may not be identified for some time,.

References

Beinstock, E. (1984). Creative problem solving (Cassette Recording). Stamford, CT: Waldentapes.

Bloom, B., Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: Longmans Green.

Bransford, J., & Stein, B. (1984). The IDEAL problem solver. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Brookfield, S. (1987). Challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

de Bono, E. (1976). Teaching thinking. London: Temple Smith.

Hopper, R., & Kirschenbaum, D. (1985). Social problem solving and social competence in preadolescents: Is inconsistency the hobgoblin of little minds? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 9, 685-701.

Kirschenbaum, H. (1977). Advanced value clarification. La Jolla, CA: University Associates.

.Newell, A., & Simon, H. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nickerson, R., Perkins, D., & Smith, E. (1985). The teaching of thinking. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

.Rubenstein, M. (1986). Tools for thinking and problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

.Stice, J. (Ed.). (1987). Developing critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Whimbey, A., & Lochhead, J. (1982). Problem solving and comprehension (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Franklin Institute Press.