Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Se. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

“Dubito ergo cogito; cogito ergo sum.”

( I doubt, therefore I think; I think therefore I am )

Rene Descartes

French Mathematician, Philosopher and Scientist

When we speak of philosophy we use a term which may be viewed in two senses. The first of these is that of the word itself which literally means “ love of wisdom” .But to love wisdom does not necessarily make one a philosopher .Today, we think of philosophy in a more limited sense as man’s attempt to give meaning to his existence through the continued search for a comprehensive and consistent answer to basic problems .It is this second sense of the word which makes the philosopher an active person; one who seeks answers, rather than one who simply sits around engaging in idle and frivolous speculation. Nowadays, most philosophers are actively concerned with life. THEY SEEK ANSWERS TO BASIC PROBLEMS. Thus we find that philosophers are doing as well as thinking, and it is their thinking which guides their doing .What they do is rooted in the search for answers to certain types of problems and the tentative answers they have formulated.

Philosophy is a persistent attempt to gain insight into the nature of the world and of ourselves by means of systematic reflection.

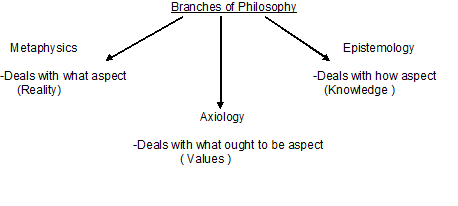

The three great problems areas of philosophy are the problems of reality, knowledge, and value-

Metaphysics: the Study of Reality

The branch of philosophy which deals with the problem of reality what is the nature of the universe in which we live? Or in the last analysis, what is real? Is termed as Metaphysics

Metaphysics: Meta means above; this is the study of the nature of things above physics.(What comes after Physics) Metaphysics covers the kinds of things most people probably think of if asked what philosophy covers e.g. those ‘big questions’, such as, is there God, why are we here, what is the ultimate nature of the universe, and so on. Another important area of metaphysics is the nature of substance, that is, what is the universe really made of,

Derived from the Greek meta ta physika (“after the things of nature”); referring to an idea, doctrine, or posited reality outside of human sense perception. In modern philosophical terminology, metaphysics refers to the studies of what cannot be reached through objective studies of material reality

Metaphysics as a disicpline was a central part of academic inquiry and scholarly education even before the age of Aristotle, who considered it “the Queen of Sciences.” Its issues were considered no less important than the other main formal subjects of physical science, medicine, mathematics, poetics and music. Since the beginning of modern philosophy during the seventeenth century, problems that were not originally considered within the bounds of metaphysics have been added to its purview, while other problems considered metaphysical for centuries are now typically subjects of their own separate regions in philosophy,.

In Western philosophy, metaphysics has become the study of the fundamental nature of all reality — what is it, why is it, and how are we can understand it. Some treat metaphysics as the study of “higher” reality or the “invisible” nature behind everything, but that isn’t true. It is, instead, the study of all of reality, visible and invisible; and what constitutes reality, natural and supernatural. Because most of the debates between atheists and theists involve disagreements over the nature of reality and the existence of anything supernatural, the debates are often disagreements over metaphysics.

In popular parlance, metaphysics has become the label for the study of things which transcend the natural world — that is, things which supposedly exist separately from nature and which have a more intrinsic reality than our natural existence. This assigns a sense to the Greek prefix meta which it did not originally have, but words do change over time. As a result, the popular sense of metaphysics has been the study of any question about reality which cannot be answered by scientific observation and experimentation. For atheists, this sense of metaphysics is usually regarded as literally empty.

Because atheists typically dismiss the existence of the supernatural, they may dismiss metaphysics as the pointless study of nothing. Because metaphysics is technically the study of all reality and thus whether there is any supernatural element to it at all, in truth metaphysics is probably the most fundamental subject which irreligious atheists should focus on. Our ability to understand what reality is what it is composed of, what “existence” means, etc., is fundamental to most of the disagreements between irreligious atheists and religious theists.

Some irreligious atheists, like logical positivists, have argued that the agenda of metaphysics is largely pointless and can’t accomplish anything. According to them, metaphysical statements cannot be either true or false — as a result, they don’t really carry any meaning and shouldn’t be given any serious consideration. There is some justification to this position, but it is unlikely to convince or impress religious theists for whom metaphysical claims constitute some of the most important parts of their lives. Thus the ability to address and critique such claims can be important.

The only thing all atheists have in common is disbelief in gods, so the only thing all atheist metaphysics will have in common is that reality doesn’t include any gods and isn’t divinely created. Despite that, most atheists in the West tend to adopt a materialistic perspective on reality. This means that they regard the nature of our reality and the universe as consisting of matter and energy. Everything is natural; nothing is supernatural. There are no supernatural beings, realms, or planes of existence. All cause and effect proceeds via natural laws.

Questions Asked in Metaphysics:

What is out there?

What is reality?

Does Free Will exist?

Is there such a process as cause and effect?

Do abstract concepts (like numbers) really exist?

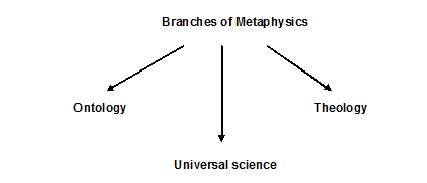

Branches of Metaphysics:

Aristotle’s book on metaphysics was divided into three sections: ontology, theology, and universal science. Because of this, these are the three traditional branches of metaphysical inquiry.

Ontology is the branch of philosophy which deals with the study of the nature of reality: what is it, how many “realities” are there, what are its properties, etc. The word is derived from the Greek terms on, which means “reality” and logos, which means “study of.” Atheists generally believe that there is a single reality which is material and natural in nature.

It is the theory of reality, the inquiry into what is real as opposed to what is appearance, either conceived as that which the methods of science presuppose, or that with which the methods of science are concerned; the inquiry into the first principles of nature; the study of the most fundamental generalizations as to what exists, and the

meaning of existence as such. and the questions relating,

Space-time or Nature as identical with existence. to explain reality in terms of matter or physical energy. (e.g., naturalism and physical realism).

Explanation regarding Spirit or God as identical with existence. To explain Existence in terms of Mind or Spirit, or to be dependent upon Mind or Spirit. (Especially true of idealism.)

To evaluate Existence as a category and its validity. As held by those, especially the pragmatists, who insist that everything is flux or change and there is nothing which fits into the category of existence in any ultimate sense

Theology, of course, is the study of gods — does a god exist, what a god is, what a god wants, etc. Every religion has its own theology because its study of gods, if it includes any gods, will proceed from specific doctrines and traditions which vary from one religion to the next. Since atheists don’t accept the existence of any gods, they don’t accept that theology is the study of anything real. At most, it might be the study of what people think is real and atheist involvement in theology proceeds more from the perspective of a critical outsider rather than an involved member.

search for “first principles” — things like the origin of the universe, fundamental laws of logic and reasoning, etc. For theists, the answer to this is almost always “god” and, moreover, they tend to argue that there can be no other possible answer. Some even go far as to argue that the existence of things like logic and the universe constitute evidence of the existence of their god

Universal science- The branch of “universal science” is a bit harder to understand,. Originally, the idea of Universal Science came from Plato’s system of idealism, formulated using the teachings of Socrates. it - moves beyond the compartmentalization of standard science, and seeks to provide a bigger picture, even a complete picture, of the cosmos and all it’s component realities. As such Unified Science tends towards grand theories of metaphysics, and estoteric world- views. It would however be simplistic and incorrect to call theories of universal science ” esoteric” and conventional science ” exoteric”. Rather universal paradigms of science are more strongly intuitive based, and in many cases are science-inspired systems of metaphysics.

Theories of Metaphysics-

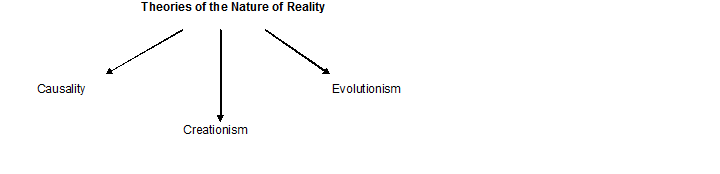

Theories of the nature of reality-( Cosmology )

Theories of the nature of the cosmos and explanations of its origin and development. It deals with the origin and structure of the universe. It accepts the principles of science and attempts to find the principles of existence, in whatever form they may take.

Some considerations in cosmology are

a . Causality. The nature of cause and effect relationship, the nature of time and the nature of space..

b Evolutionism .universe evolved by itself.

c .Creationism. The universe came to be as the result of the working of a creative cause or Personality.

Theories of nature of man as one important aspect of Reality.

The problem of essential nature of the self. There are no particular terms but there are divergent answers which can be identified with general viewpoints.

- The self is a soul, a spiritual being. A principle of idealism and spiritual realism.

2. The self is essentially the same as the body. A principle of naturalism and physical realism

3. The self is a social-vocal phenomenon. A principle held especially by experimentalists

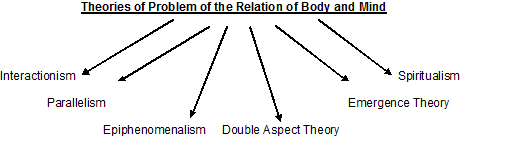

Theories of Problem of the Relation of Body and Mind

- Interactionism. Mind and body are 2 different kind of reality, each of which can affect the other.

- Parallelism. Mind and body are two different kinds of reality which do not and cannot affect each other. But in some unknown way, every mental event is paralleled by a corresponding physical event.

- Epiphenomenalism. Mind is merely a function of the brain, an overtone accompanying bodily activity. It is an onlooker at events, never influencing them.

- Double Aspect Theory. Mind and body are two aspects of a fundamental reality whose nature is unknown.

- Emergence Theory. Mind is something new which has been produced by Nature in the evolutionary process, neither identical with body, parallel to it, nor wholly dependent upon it.

- Spiritualism (A definition common to most idealists and spiritual realists.) Mind is more fundamental than body. The relation of body and mind is better described as body depending upon mind, as compared to the common-sense description according to which mind depends upon body.

Theories of problem of freedom

- Determinism. Man is not free. All of his actions are determined by forces greater than he is

- Free Will. Man has the power of choice and is capable of genuine initiative

- There is a third alternative proposed especially by the experimentalists, for which there is no name. Man is neither free nor determined; but he can and does delay some of his responses long enough to reconstruct a total response, not completely automatic but not free, which does give a new direction to subsequent activity.

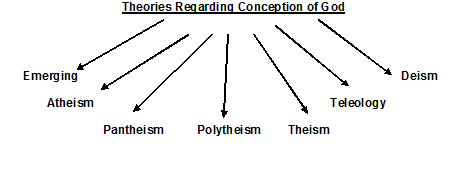

Theories Regarding Conception of God

1. Atheism. There is no ultimate reality in or behind the cosmos which is Person or Spirit.

2. Deism. God exists quite apart from, and is disinterested in, the physical universe and human beings. But He created both and is the Author of all natural and moral law.

3. Pantheism. All is God and God is all. The cosmos and God are identical.

4. The conception of God as emerging, for which there is no common name. God is evolving with the cosmos; He is the end toward which it is moving, instead of the beginning from which it came.

5. Polytheism. Spiritual reality is plural rather than a unity. There is more than one God.

6. Theism. Ultimate reality is a personal God who is more than the cosmos but within whom and through the cosmos exists.

7. Teleology. Considerations as to whether or not there is purpose in the universe.

Philosophies holding that the world is what it is because of chance, accident, or blind mechanism are no teleological.

Philosophies holding that there has been purpose in the universe from its beginning, and /or purpose can be discerned in history, are teleological philosophies.

It may be that a special case must be made of the experimentalists again on this particular question, as they do not find purpose inherent in the cosmos but by purposeful activity seek to impose purpose upon it.

Theoretical Considerations relating to the constancy, or lack of it, in reality.

Absolutism. Fundamental reality is constant, unchanging, fixed, and dependable

Relativism. Reality is a changing thing. So called realities are always relative to something or other.

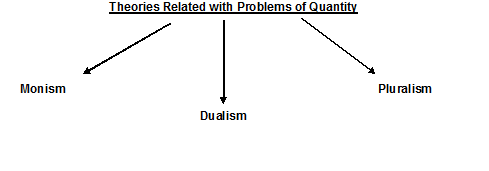

Theories Related with Problems of quantity. Consideration of the number of ultimate realities, apart from qualitative aspects.

Monism. Reality is unified. It is one. It is mind, or matter, or energy, or will but only one of these.

Dualism. Reality is two. Usually these realities are antithetical, as spirit and matter, good and evil. Commonly, the antithesis is weighted, so that one of the two is considered more important and more enduring than the other.

Pluralism. Reality is many. minds, things, materials, energies, laws, processes, etc., all may be considered equally real and to some degree independent of each other.

References

Brameld, Theodore, Philosophies of Education in Cultural Perspective. New York: Dryden Press, 1956.

Butler, J.Donald, Four Philosophies and Their Practice in Education and Religion. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1957

Cotter, A.C. ABC of Scholastic Philosophy. Weston, Massachusetts: Weston College Press, 1949

Maritain, Jacques,” Thomist views on Education,” Modern Philosophies of Education. National Society for the Study of Education, Fifty-Fourth yearbook, Part I. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955.

Weber, Christian O., Basic Philosophies of Education. New York : Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1960. This book, especially in chapters 11-14,

Broudy, Harry S., Building a Philosophy of Education. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1961..

Frank Thilly, “A History of philosophy”, Central Publishing House, Allahabad.

Rusk, R.R., “Philosophical Basis of Education” p-68, footnote, London, University of London Press, 1956.

Acknowledgement

Shubhi, for being the scribe of this aricle.