Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A. (Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D.

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

For the realist, the world is as it is, and the job of schools would Thus, the realism has brought great effect in various fields of education. The aims, the curriculum, the methods of teaching the outlook towards the child, the teachers, the discipline and the system of education all were given new blood. Realism in education dragged the education from the old traditions, idealism and the high and low tides to the real surface.

REALISM IS THE REFINEMENT OF OUR COMMON ACCEPTANCE OF THE WORLD AS BEING JUST WHAT IT APPEARS TO BE. According to it, things are essentially what they seem to be ,and, furthermore, in our knowledge they are just the same as they were before entering our consciousness, remaining unchanged by our experiencing them.

Historical Retrospect

Although some of the early pre-Christian thinkers dealt with the problems of the physical world (most notably the early Greek physicist- philosophers, Democritus and Leucippus) the first detailed realistic position is generally attributed to Aristotle. Reality, according to Aristotle was distinguishable into form and matter. Matter is the substance that all things have in common. For Aristotle these to substance were logically separable although always found together in the empirical world.

Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century:

John Amos Comenius emphasizes the primary importance of the gathering of knowledge or sense data.. Comenius felt that the human mind, like a mirror, reflected everything around it.

John Locke was a philosopher as Comenius was an educator. Locke’s greatest contribution both to philosophy and to philosophy of education was his doctrine that ideas are not innate but that all experience is the result of impressions made on the mind by external objects. The implication of this are spelled out in his concept of the tabula rasa or the mind as a blank sheet on which the outside world must leave its impressions. All ideas, according to Locke, must come from either sensation or reflection.

American Realism: The New Realists and the Critical Realists

New Realists, particularly the American school, rejected this notion, giving mind no special status and viewing it as part of nature. For them things could pass in and out of knowledge and would in no way be altered by the process. Existence, they argued, is not dependent upon experience or perception, thus mind ceases to be the central pivot of the universe.

Herbart the new rationalist, argued that all subjects are related and that Knowledge of one helps strengthen knowledge of the others. The relationships between new ideas and old ideas occurred in what Herbart called the apperceptive mass. Within the mind, new apperceptions or presentations united with older apperceptions and struggled to rise from the unconscious level of mind to the conscious.

Philosophical Rationale of Realism

Realism is interested in objects and facts. In general, realists believe in the independent existence of the experiential universe. They have a healthy respect for the “facts” of both the sciences and the social sciences.

Let us look at the old question about the falling tree on the desert island for a moment. The question is usually as follows: “If a tree falls on a desert island and there is no one there to hear it, is there any sound?” How would the idealist and the realist differ in looking at and answering this particular question? If objects exist independent of any knowledge about them, it is obvious that we have an irreconcilable dispute between the realists and the idealists. Where an idealist would say that a tree in the middle of the desert exists only if it is in some mind, or if there is knowledge of it; the realist would hold that whether or not anyone or anything is thinking about the tree, it nonetheless exists. The realist has revolted against the doctrine that things that are in the experiential universe are dependent upon a knower for their existence.

The Universe (Ontology or Metaphysics)

There is great variety in the metaphysical beliefs of realists. There is so much variety, in fact, that realists could never be grouped together if they did not have certain common ground. They believe that the universe is composed of matter in motion. It is the physical world in which we live that makes up reality. We can, on the basis of our experiences, recognize certain regularities in it about which we generalize and to which we grant the status of laws. The vast cosmos rolls on despite man. It is ordered by natural laws which control the relationships himself with it or not. It is not unlike a giant machine in which man is both participant and spectator. This machine not only involves the physical universe, it operates in the moral, social and economic sphere as well. The realist sees the immutable laws governing man’s behavior as part of the machine; they are natural law.

The realist may be a monist, believing in one substance; a dualist, believing in two; or a pluralist, believing in many. Whichever he is, he believes that all substances have a real existential status independent of the observer. He sees the world as having an orderly nature and composition which exists independent of consciousness but which man may know.

Of the several, different answers to the problem of GOD, it is likely that everyone is upheld by some member of the family of realists. Of course, there are realists who are atheistic. Those who define mind in terms of matter or physical process, and who think of the cosmos in the thoroughly naturalistic sense,ofcourse have no place for God in there metaphysics.

Knowledge and Truth (Epistemology)

. Basically, there are two different schools of epistemological thought in the realist camp. While both schools admit the existence and externality of the “real” world, each views the problem of how we can know it in a different way. The realists have been deeply concerned with the problems of epistemology. Realists pride themselves on being “hard-nosed” and not being guilty of dealing with intellectual abstractions

The first position or presentational view of knowledge holds that we know the real object as it exists. This is the positions of the New Realists. When one perceives something, it is the same thing that exists in the “real” world. Thus, mind becomes the relationship between the subject and the object. In this school of thought there can be no major problems of truth since the correspondence theory is ideally applicable. This theory states that a thing is true is as it corresponds to the real world. Since knowledge is by definition correspondence, it must be true.

These real entities and relations can be known in part by the human mind as they are in themselves. Experience shows us that all cognition is intentional or relational in character. Every concept is of something; every judgment about something.

Concept of Good (Axiology)

The realist believes in natural laws. Man can know natural law and live the good life by obeying it. All man’s experience is rooted in the regularities of the universe or this natural law. In the realm of ethics this natural law is usually referred to as the moral law. These moral laws have the same existential status as the law of gravity in the physical sciences or the economic laws which are supposed to operate in the free market. Every individual has some knowledge of the moral and natural law.

Realist believes that those qualities of our experience, which we prefer or desire, and to which we attach worth, have something about them which makes them preferable or desirable. But according to the second theory, the key to the evaluation is to be found in the interest.

Social Value- The moral good can be defined from the vantage point of society as “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.”

Religious Value

One aspect of the relation of axiology and metaphysics can be seen by looking again at what has been said about realism and belief in God,. For those who do not believe in God, experience will not be rooted in a Divine Being whom we can worship, reverence, and in whom we can place our trust. Faith and hope will not have validity as religious attitudes because they will have no real object.. But there are also realists who believe in God: and for them many traditional religious values are rooted in realty and therefore are valid.

Concept of Beauty (Aesthetics)

There is a close relation between the refinement of perception and the ability to enjoy aesthetic values. It holds that ultimate values are essentially subjective. In other words, he believes that no goal or object is bad or good in itself. Only the means for acquiring such goals or objects can be judged good or bad insofar as they enable the individual or the group to attain them.

Since the realist place so much value on the natural law and the moral law as found in the behavior or phenomena in nature, it is readily apparent that the realist will find beauty in the orderly behavior of nature. A beautiful art form reflects the logic and order of the universe. Art should attempt to reflect or comment on the order of nature. The more faithfully and art form does this, the more aesthetically pleasing it is.

Logic of Realism

It can be seen that for realism there is logic of investigation as well as a logic of reasoning. The one functions largely at the level of sense perception, the other more especially at the conceptual level. Both are important in any effective adjustment to the real world and in any adequate control of our experience.

Montague suggests still other ‘ways of knowing’ which have their contribution to make to the material of logic

(1)The accepting of authoritative statements of other people, he says ‘ must always remain the great and primary source of our information about other man’s thoughts and about the past

’(2)Intuition, of the mystical sort, ay also be a source of truth for us, but we should always be careful to put such knowledge to the test of noninituitative methods before accepting it

.(3) Particularly in the realm of practical or ethical matters, the pragmatic test, ‘how effective it is in practice’ may be a valid source of truth

(4) And even skepticism also has its value in truth-seeking; it may not yield any positive truth for us but it can save us from cockiness and smugness, and help us to be tolerant and open minded.

Bertrand Russell, who came to philosophy by way of mathematics, has always held that particular science in high repute as an instrument of truth. As is the case with many realists. He feels that traditional logic needs to be supplemented by the science of mathematics because of the inaccuracy and vagueness both of words and grammer.He thinks that if logical relations are to be stated accurately .they must be represented by mathematical symbols and equations, words are too bungle some.

Concept of Society

From the foregoing, it should now be apparent that the social position of this philosophy would closely approximate that of idealism. Since the concern of this position is with the known, and with the transmission of the known, it tends to focus on the conservation of the cultural heritage. This heritage is viewed as all those things that man has learned about natural laws and the order of the universe over untold centuries. The realist position sees society as operating in the framework of natural law. As man understands the natural law, he will understand society.

Realism: in Education

From this very general philosophical position, the Realist would tend to view the Learner as a sense mechanism, the Teacher as a demonstrator, the Curriculum as the subject matter of the physical world (emphasizing mathematics, science, etc.), the Teaching Method as mastering facts and information, and the Social Policy of the school as transmitting the settled knowledge of Western civilization. The realist would favor a school dominated by subjects of the here-and-now world, such as math and science. Students would be taught factual information for mastery. The teacher would impart knowledge of this reality to students or display such reality for observation and study. Classrooms would be highly ordered and disciplined, like nature, and the students would be passive participants in the study of things. Changes in school would be perceived as a natural evolution toward a perfection of order.

For the realist, the world is as it is, and the job of schools would be to teach students about the world. Goodness, for the realist, would be found in the laws of nature and the order of the physical world. Truth would be the simple correspondences of observation. The Realist believes in a world of Things or Beings (metaphysics) and in truth as an Observable Fact. Furthermore, ethics is the law of nature or Natural Law and aesthetics is the reflection of Nature.

Aims of Education:

Realists do not believe in general and common aims of education. According to them aims are specific to each individual and his perspectives. And each one has different perspectives. The aim of education should be to teach truth rather than beauty, to understand the present practical life. The purpose of education, according to social realists, is to prepare the practical man of the world.

The science realists expressed that the education should be conducted on universal basis. Greater stress should be laid upon the observation of nature and the education of science.Neo-realists aim at developing all round development of the objects with the development of their organs.

The realist’s primary educational aim is to teach those things and values which will lead to the good life. But for the realist, the good life is equated with one which is in tune with the overarching order of natural law. Thus, the primary aim of education becomes to teach the child the natural and moral law, or at least as much of it as we know, so that his generation may lead the right kind life; one in tune with the laws to the universe. There are, of course, more specific aims which will lead to the goals already stated. For example, realists set the school aside as a special place for the accumulation and preservation of knowledge.

Realists just as other philosophers have expressed the aims of education in various forms. According to John Wild the aim of education is fourfold to discern the truth about things as they really are and to extend and integrate such truth as is known to gain such practical knowledge of life in general and of professional functions in particular as can be theoretically grounded and justified and finally to transmit this in a coherent and convincing way both to young and to old throughout the huEducation should guide the student in discovering and knowing the world around him as this is contained in the school subjects.

Russell follows the same line of reasoning in his discussion of educational objectives. He too would not object to the school’s assisting the child to become a healthy happy and well-adjusted individual. But he insists that the prime goal of all school activities should be the development of intelligence. The well-educated person is one whose mind knows they would as it is. Intelligence is that human function which enables one to acquire knowledge. The school should do all in its power to develop intelligence.

Concept of Student:

Realism in education recognizes the importance of the child. The child is a real unit which has real existence. He has some feelings, some desires and some powers. All these cannot be overlooked. These powers of the child shall have to be given due regarding at the time of planning education. Child can reach near reality through learning by reason. Child has to be given as much freedom as possible. The child is to be enabled to proceed on the basis of facts; The child can learn only when he follows the laws of learning.”

Broudy describes the pupil by elaborating four principles which, according to him, comprise the essence of the human self. These are the appetitive principle the principle of self-determination the principle of self-realization and the principle of self-integration.

The appetitive principle, mentioned first, has to do with the physiological base of personality. Our appetites disclose the need of our tissues to maintain and reproduce themselves. Physiological life, and therefore the life of personality, cannot go on unless these necessary tissue needs are supplied. In order for us to do anything about our tissue needs, except on an animal level, we must be aware of them; and in being aware of them, we realize that pleasure and pain are central.

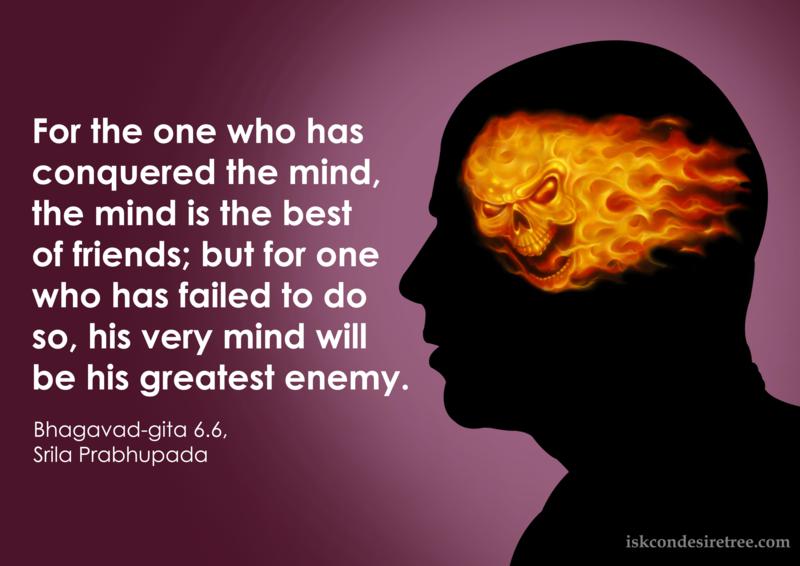

The self has continuity formal structure antecedents in the past and a yearning toward the future. Our experience has some continuity throughout changing events and places and in order to explain this we must recognize that the self is a common factor in all of these experiences even though there are gaps in consciousness such as when we are asleep or under anesthesia. The self has form as well as continuity. As for determinism rationality requires that we recognize the validity and dependability; of cause-and-effect relations but we do not need to hold to determinism with the meaning that all of our experience is the result of physical forces. Our power to symbolize is one element of our experience that does not bear out the truth of this kind of determinism.

The third principle of selfhood, self-realization supplements freedom as such with value concerns. Freedom does not carry built-in guarantees that it will be turned to good ends. In order to be freedom it must be free to make us miserable. The how of choosing, as well as the what which is chosen is a necessary ingredient of the good life.

The child is to be understood a creature of the real world there is no sense in making him a God. He has to be trained to become a man only. To the realist, the student is a functioning organism which, through sensory experience, can perceive the natural order of the world. The pupil, as viewed by many realists, is not free but is subject to natural laws. It is not at all uncommon to find realists advocating a behavioristic psychology. The pupil must come to recognize and respond to the coercive order of nature in those cases where he cannot control his experiences, while learning to control his experiences where such control is possible. At its most extreme, the pupil is viewed as a machine which can be programmed in a manner similar to the programming of a computer.

Concept of Teacher

From this very general philosophical position, the Realist would tend to view the Learner as a sense mechanism, the Teacher as a demonstrator, the Curriculum as the subject matter of the physical world (emphasizing mathematics, science, etc.), the Teaching Method as mastering facts and information, and the Social Policy of the school as transmitting the settled knowledge of Western civilization. The realist would favor a school dominated by subjects of the here-and-now world, such as math and science. Students would be taught factual information for mastery. The teacher would impart knowledge of this reality to students or display such reality for observation and study. Classrooms would be highly ordered and disciplined, like nature, and the students would be passive participants in the study of things. Changes in school would be perceived as a natural evolution toward a perfection of order.

For the realist, the world is as it is, and the job of schools would Thus, the realism has brought great effect in various fields of education. The aims, the curriculum, the methods of teaching the outlook towards the child, the teachers, the discipline and the system of education all were given new blood. Realism in education dragged the education from the old traditions, idealism and the high and low tides to the real surface.

The teacher, for the realist, is simply a guide. The real world exists, and the teacher is responsible for introducing the student to it. To do this he uses lectures, demonstrations, and sensory experiences, The teacher does not do this in a random or haphazard way; he must not only introduce the student to nature, but show him the regularities, the “rhythm” of nature so that he may come to understand natural law. Both the teacher and the student are spectators, but while the student looks at the world through innocent eyes, the teacher must explain it to him, as well as he is able, from his vantage point of increased sophistication. For this reason, the teacher’s own biases and personality should be as muted as possible. In order to give the student as much accurate information as quickly and effectively as possible, the realist may advocate the use of teaching machines to remove the teacher’s bias from factual presentation. The whole concept to teaching machines is compatible with the picture or reality as a mechanistic universe in which man is simply one of the cogs in the machine.

A teacher should be such that he himself be educated and well versed with the customs of belief and rights and duties of people, and the trends of all ages and places. He must have full mastery of the knowledge of present life. He must guide the student towards the hard realities of life. He is neither pessimist, nor optimist. He must be able to expose children to the problems of life and the world around.

The Curriculum:

According to humanistic realism, classical literature should be studied but not for studying its form and style but for its content and ideas it contained.

Sense-realism- attached more importance to the study of natural sciences and contemporary social life. Study of languages is not so significant as the study of natural sciences and contemporary life.

Neo-realism- gives stress on the subject physics and on humanistic feelings, physics and psychology, sociology, economics, Ethics, Politics, history, Geography, agriculture varied arts, languages and so on, are the main subjects to be studied according to the Neo-realists

Subject matter is the matter of the physical universe- the Real World- taught in such a way as to show the orderliness underlying the universe. The laws of nature, the realist believes, are most readily understood through the subjects of nature, namely the sciences in all their many branches. As we study nature and gather data, we can see the underlying order of the universe. The highest form of this order is found in mathematics. Mathematics is a precise, abstract, symbolic system for describing the laws of the universe. Even in the social sciences we find the realist’s conception of the universe shaping the subject matter, for they deal with the mechanical and natural forces which bear on human behaviour. The realist views the curriculum as reducible to knowledge position espoused by E.L. Thorndike that whatever exists must exist in some amount and therefore be measurable.

John Wild, while differing slightly from the foregoing analysis, describes the ordering of the curriculum in such a way as to indicate his philosophical orientation toward realism.

There is certainly a basic core of knowledge that every human person ought to know in order to live a genuinely human life…..First of all the student should learn to use the basic instruments of knowledge, especially his own language. In order to understand it more clearly and objectively, he should gain some knowledge of at least one foreign language as well. In addition, he should be taught the essentials of humane logic and elementary mathematics. Then he should become acquainted with the methods of physics, chemistry and biology and the basic facts so far revealed by these science. In the third place he should study history and the sciences of man. Then he should gain some familiarity with the great classics of his own and of world literature and art.

Finally in the later stages of this basic training, he should be introduced to philosophy and to those basic problems which arise from the attempt to integrate knowledge and practice.

Wild goes on to point out the orderly nature of the universe and indicate that it is possible to find certain “solidly grounded” moral principles, and that these, along with the core of subject matter “based on the nature of our human world, should be given to everyone.”

The Instructional Methodology:

The method of the realists involves teaching for the mastery of facts in order to develop an understanding of natural law. This can be done by teaching both the materials and their application. In fact, real knowledge comes only when the organism can organize the data of experience. The realist prefers to use inductive logic, going from the particular facts of sensory experience to the more general laws deducible from these data. These general laws are seen as universal natural law.

When only one response is repeated for one stimulus, it conditioned by that stimulus. Now wherever that situation comes, response will be the same; this is the fact.

For Herbart, education was applied psychology. The five-step method he developed was as follows:

Preparation: An attempt is made to have the student recall earlier materials to which the new knowledge might be related. The purpose of the lesson is explained and an attempt to interest the learner is made.

Presentation: The new facts and materials are set forth and explained.

Association: A definite attempt is made to show similarities and differences and to draw comparisons between the new materials and those already learned and absorbed into the apperceptive mass.

Generalization: The drawing of inferences from the materials and an attempt to find a general rule, principal, or law.

Application: In general this meant the working of academic exercises and problems based on both the new information and the relevant related information in the appreciative mass.

“(There are and can be only two ways for investigation and discovery of truth. One flies from senses and particulars, to the most general axioms and from these principles and infallible truth determines and discovers intermediate axioms….the other constructs axioms from the senses and particulars by ascending continually and gradually, so as to teach most general axioms last of all.)” – Bacon.

In their method, the realist depends on motivation the student. But this is not difficult since many realists view the interests of the learner as fundamental urges toward an understanding of natural law rooted in our common sense. The understanding of natural law comes through the organizing of data through insight. The realist in their method approves anything which involves learning through sensory experience whether it be direct or indirect. Not only are field trips considered valuable, but the realist advocates the use of films, filmstrips, records, television, radio, and any other audiovisual aids which might serve in the place of direct sensory experience when such experience is not readily available. This does not mean that the realist denies the validity of symbolic knowledge. Rather it implies that the symbol has no special existential status but is viewed simply as a means of communicating about, or representing, the real world.

A teacher should always keep in mind-

- Education should proceed from simple to complex and from concrete to abstract.

- Students to be taught to analyze rather than to construct.

- Vernacular to be the medium of instruction.

- Individual’s experience and spirit of inquiry is more important than authority.

- No unintelligent cramming. More emphasis on questioning and understanding.

- Re-capitulation is necessary to make the knowledge permanent.

- One subject should be taught at one time.

- No pressure or coercion be brought upon the child.

- The uniformity should be the basic principle in all things.

- Things should be introduced first and then the words.

- The entire knowledge should be gained after experience.

- There should be a co-relation between utility in daily life and education.

- The simple rules should be defined.

- To find out the interest of the child and to teach accordingly.

Concept of Discipline:

Discipline is adjustment the individual in the educational program. Such preoccupation with the individual flouts the reality to objectivity. It is necessary in order to enable the child to adjust himself to his environment and concentrate on his work. Bringing out change in the real world is impossible. The student himself is a part of this world. He has to admit this fact and adjust himself to the world.

A disciplined student is one who does not withdraw from the cruelties, tyrannies, hardships and shortcomings pervading the world. Realism has vehemently opposed withdrawal from life. One has to adjust oneself to this material world.

The student must be disciplined until he has learned to make the proper responses. Wild says of the student that it is. His duty…. to learn those arduous operations by which here and there it may be revealed to him as it really is. One tiny grain of truth is worth more than volumes of opinion.

The School:

John Amos Comenius in his great didactic describes the unique function of the school in a manner which will symbolize modern realism. He said that man is not made a man only by his biological birth. If he is to be made a man. Human culture must give direction and form to his basic potentialities. This necessity of the school for the making of man was made vivid for Comenius by reports which had come to him of children who had been reared from infancy by animals. The recognition of this by Comenius caused him to consider the education of men by men just as essential to man birth, as a human creature, as is procreation. He therefore defined education as formation and went so far as to call the school ‘a true forging place of man’

Evaluation of Realism in Education:

In educational theory and practice, the scientific realists might be criticized for the following reasons:

Realism treats metaphysics as meaningless. The realists make no provision for the world of supernature and takes an agonistic view towards it. Most of the propositions of traditional metaphysics are relegated to the realm of irrelevancy.

There is no role for functions as creative reason in realism. One reason for this flows from the monoistic assumption that the known and the knower are of the same nature. There is no role for such functions as creative reason- in the sense that reason can form abstractions from sense data.

The epistemology of the realists is inadequate. In realism only empirical knowledge is recognized as valid with in their system. The passive aspects of the knowing process are overemphasised by realists.

There is too much emphasis on the individual in realism .Some of them place too much emphasis on of the complexity and interdependence of modern society.

Stress on content much more than the methods: The scientific realists with the exception or Russell stress content much more than the methods of acquiring knowledge. This emphasis often leads to rote memorization one of the major weaknesses of the traditional school. Thus lip service may be paid to the goals of developing critical thinking understanding and other complex intellectual functions but little is done by the student to attain these goals.

In realism there is little attention for developing an educational theory. Most of the philosophical realists of this school pay little or no attention to developing an educational theory consistent with their basic philosophical beliefs as Dewey, broody, Adler, And Martian have done.

There is too much emphasis on sense experience in realism .The realist does not accept the existence of transcendental ( not based on experience or reason ) being. How could be know the non-existence of that which does not exist? Has non-existence got no existence ? Void ness and non-existence also are the parts of existence. Here the realist is dumb completely.

The realist recognizes the origin of knowledge from the datum achieved by senses and asserts that only objects are main and it is through their contact that knowledge is acquired. Then how does our illusion arise ? How does knowledge become fallacious? Where does the external object go in dream ? The realist is unable to answer these questions satisfactorily.

The curriculum proposed by most realist is one-sided. Today the effect of realism has given rise to the wave of science. It is right, but there should be no indifference towards art and literature. The realist supports this negligence The curriculum proposed by most scientific realists is one-sided since empirical knowledge holds a position superior to that of the humanistic studies. This neglect is evident in the absence of a well defined theory of age and art education.

There is no place to imagination ,pure thoughts and sentimentsin realism. Realism admits real feelings and needs of life on the one hand, gives no place to imagination and sentiment, on the other. What a contradiction? Are imaginations, emotions and sentiments not real needs of human life? Is emotionless life not almost dead life? Can life be lead on the basis of facts only?

The realist claims to be objective. Objectivity in knowledge is nothing but the partnership of personal knowledge. Knowledge is always subjective.”

Realism recognizes only the real existence of the material world. This recognition remains not objected to unless he says that only material world really exists. The question arises- Is there no power behind this material world? Does it have its own existence? What is the limit of the universe? The realist does give reply to these questions but these replies are not found to be satisfactory. The real existence of material world may be admitted but how can the existence come to an end in the world itself.

Realism enthuses disappointment in students and teachers. No progress can be made by having faith in the facts of daily life and shattering faith in ideals. Life is but full of miseries and struggles. Sorrow is more predominant than joy in the world. A person becomes disappointed by this feeling. That is why realists often appear to be skeptics, Pessimists and objectionists,

Realism encourages formalism. The Herbartian movement in the United States reached its peak in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Because of its formalism it allowed a teacher to substitute technique for knowledge a long distance. It became a popular technique to impart to future teachers in normal schools and in other institutes for teacher preparation. Its very formalism was also its greatest weakness since it allowed a teacher slavishly to develop a lesson with allowed the rigid teacher to teach rigidly. Herbart himself would probably have shuddered at the misuse of what he conceived of as creative method for teaching children.

Both the New Realists and the Critical Realists failed to provide a satisfactory answer to the problem of error. The New Realist position is the weaker of the two since direct cognition does not permit error and the rationale employed by Wild, that “Error is the creation of the erring subject” is most unsatisfactory if the mind is viewed purely as relational with no contents of its own with which to create error. The Critical Realists have solved the problem of error, but in doing so through the use of an intermediary or vehicle of knowledge; they have created a whole new host of problems in terms of defining and explaining the nature of the vehicle. Whether it is of the substance of mind, matter, or some neutral substance is unclear and varies with the particular philosopher one is reading. Both positions, despite their differences, create problems for the educator. The New Realist position with regard to error is manufacture unable, and the

There is danger of encouraging elitism. Finally, the same criticism of absolutes applies to the realists as applied to the idealists. There is the constant danger that there will arise a class of persons who be the ones with the responsibility of identifying and arbitrating questions concreting absolutes. These may be priests in an idealist society or scientist in a realist society, but whatever they are, they become an external source of authority in an area in which people should be speculating and the danger of an inquisition is always inherent in such a social structure. Whenever we allow any person or group of persons to tell us what is Truth and what is not Truth, and permit them the authority to force this point of view on us, we are in danger of losing the very essence of the truly democratic society.

Realism depends on cause- effect relationships. The next criticism deals directly with the philosophical underpinnings of the realist position. Almost all the laws of nature that the realists stress are dependent upon cause- effect relationships. Most philosophers and scientists are chary of such absolutes. They prefer to deal in the realm of probability. Past activity is no guarantee of future activity. Because the sun rises in the East every day is no guarantee that it will rise there tomorrow, although the probability is ridiculously high. Thus, to teach moral absolutes and natural laws is a highly questionable procedure.

Realism fails to deal with social change. Like the idealists, the realists are basically conservative in education. Rather than concern themselves with social change and educational progress they are most concerned with preserving and adding to the body of organized truth they feel has been accumulated. In a period when there was little social change occurring this type of philosophy may have been adequate. But in an increasingly automated society operating on an ever-expanding industrial base, many educators feel that education must be a creative endeavour, constantly looking for new solutions to problems. This role appears to be incompatible with the realist’s fundamental conception of the role of education in the society.

In short realism rejects or disregards the supernatural, and likewise denies duality in man’s nature or any distinction of cognitive powers into sensory and intellectual. Realists hold that man can know reality, and that he does so through inductive experience.