Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

A nation’s prosperity and success depend upon wisdom like that of Krishna and on bravery like that of Arjuna. The one without other is incomplete and defective. Efficiency can best be secured by a combination of both. This is corollary to the Bhagawad-Gita; disinterested performance of one’s duty, without attachment to its fruit, at any cost and any risk, being its burthen. This is a message of all times to come for men in general ,but this is THE message for the descendants, successors and countrymen of Krishna and Arjuna, swayed as they are, at present, by the forces of ignorance, superstition, chicken-heartedness and false ideas of Dharma and Karma. In unswerving loyalty to this truth-at any cost and under any circumstances- lies the salvation of the present-day Indians. If ever any nation stood in need of a message like that of Krishna, it is the Indians of to-day. If ever the inheritors of Krishna’s name and glory stood in need of a sound doctrine to lead them to success and prosperity amidst adverse circumstances of the greatest awe-inspiring and fear-generating magnitude, it is now.

In the whole range of Sanskrit literature there is hardly any other book which is so popular and widely read and admired by all classes of Hindus as “The Bhagwad Gita” or the “The Lord’s Song.” The Mahabharata contains several Gitas, but it is the Bhagwad Gita alone which is meant and understood when people talk of the Gita. Of all the scared books of the Hindus (its sacredness being unquestionably admitted by all), the Gita is perhaps the only one which is so extensively read, admired and relied on, by all Hindu Sampradayas (religious sects and schools of theology), orthodox or heterodox, reformed or unreformed.

But while the Vedas are a sealed book to a vast majority, the Gita is open and intelligible to a large number. They can read it, understand it, and interpret it, every one in his own way. It is a thing which at once appeals to their intelligence as well as their emotions. It gives them plenty of scope for reflection, and spiritual exercise. It is rigid and elastic at the same time. It broadens the vision and expands the outlook without requiring a serious outrage on the affections. It is invigorating as well as chastening. It stimulates one’s energies and subdues one’s passions. It is a constant and ever recurring exhortation in favour of right action without attachment to its results. It shows the way to the balancing of the mind, assigning their proper places to the activities of the body and the yearnings of the soul. It is a most audacious as well as a most successful attempt to reconcile the different schools of religious thought that prevailed in ancient India at the time of its composition. But what makes it so universally acceptable is its attempt to answer the one great question that has troubled the human soul in all times and that is always present to the eyes of the mind under all circumstances, viz., how to reconcile the apparent contradictions of life. Here we are in this world of conflict, struggle and strife, more often surrounded by sin and sorrow than by virtue and happiness, more dejected by the pettiness and meanness encompassing us, than held up by the broadness of soul and the sympathy of heart which we only now and then experience; more depressed by the inconsistencies of life, the selfishness, the narrowness, the ugliness and the utter depravity of human nature than elevated by that much-sought-after and much-talked-of harmony that is said to prevail in the world.

The Gita or the Lord’s Song is an attempt to answer that question for all and for all times to come. Hence its universal popularity amongst and acceptability to all classes of people, irrespective of their differences in creed, caste and colour. How to show that, apparent contradictions notwithstanding, the world is still a consistent whole, how to reconcile the conflict between duty and sentiment is the burden of the Gita.

Standing on the field of battle between the two hosts of combatants ready to kill one another, Arjuna, the Pandu Prince, found himself perplexed by the idea of killing his kith and kin, those to whom he was bound by all the ties that are sacred and dear in this world, Naturally enough he felt appalled at the idea of having to kill a Guru like the celebrated Dronacharya and a grand-father like Bhishma, for the sake of either of whom he would be most willing to lay down his own life. But here he was required to kill them for the sake of obtaining a kingdom for himself and his brothers. He knew well that so long as they viz., Bhishma and Drona, were in the field, fighting for the opposite side, there could be no chance of his vanquishing his adversaries.. As a sishya (a disciple) , as a grandson, as a brother, as a friend and as a man, it was a sin for him to attempt the lives of those who stood in the opposite ranks; as a prince and as a warrior; even as a brother of Yudhishthira, husband of Draupadi, son of Kunti, it was his duty to fight for the deliverance of his nation”; to restore to his brother what was lawfully and by right . Apparently slaying was a greater sin than the neglect of other duties and hence Arjuna’s inclination to retire from the battle. But then there was Lord Krishna with him, who had come to help him in the performance of his duty as a warrior and to support him by his wisdom, as he had vowed to wield arms for no party in this family war. He saw his duty clear before him. To his knowing eyes it was only disgraceful but sinful as well (perhaps more sinful than disgraceful) for a person born and bred as a Kshattriya, to be borne down by such chicken-hearted skepticism just at the time of action, in the field of battle and in the presence of the enemy. To allow this to happen would have been nothing short of criminal on the part of a greater teacher like Krishna, because that would have been allowing fraud, dishonesty, deceit and wrongful usurpation of other people’s rights to go unpunished and unrighted. Krishna was hardly a man to let this happen, at least without an effort to save the situation. So he set to his task. How he performed it, with what logic and with what success, is the subject matter of Gita.

The doubt that troubled Arjuna is a very common one. It haunts human beings day and night, and the number of those who actually succumb to it is by no means small. It is a source of constant mental conflict in the East as well as in the West. It makes no distinction of caste and colour. It is, however, difficult to have a Krishna at your side every time this demon of doubt threatens to lead you astray. Hence the value of the eternal message conveyed for all and for all ages by the Lord’s Song called Bhagawad Gita.

The story of the Gita is so natural and human, that it directly and irresistibly appeals to the innermost core of every seeker after truth. It starts where it just catches the heart of man in the natural course of life. It anticipates the various pit-falls into which he is likely to fall in his attempt to grapple with the problem of life, and then gradually extricates him from the meshes of doubt. This latter function is performed with such skill and such mastery of human nature as to make every prototype of Arjuna feel that he is at home and ending with the Divine, winding up with a detail account of the way and means of reaching the Divine. Professing all along to deal with the deepest philosophy of life, not unoften speaking in the language of mystery, it always concluded in such a way as to make it appear an open secret. Discoursing on philosophy and science, discussing the most incomprehensible and abstruse of all the questions that ever arise before the mental vision of man, -the question of what is Life and Death- solving for you the great riddle of existence and non-existence, in short, unfolding before your eager and wondering eyes the great mystery of creation and man’s place therein, it speaks to you in tones of the most captivating music. Thus it combines splendid prose with sublime poetry and thrills the listener with the vibrations of its strings, harmonized and touched by a master hand. The fact that the Gita is a song set to music by a great mind is often ignored by those who seek its support for their own pet doctrines and dogmas. Its repetitions and apparent contradictions puzzle them and they set themselves to reconcile the same, forgetting altogether the extremely human and natural origin of the song. The book was never composed to serve as doctrinal or polemical treatise. The dialogue did not begin with a question of theology or religion or philosophy. It began with the unwillingness of Arjuna to slay his own relatives and friends.

The Mahabharata, as we have it, must very largely and repeatedly tampered with, and no one can say with confidence that the Gita has altogether escaped the meddlesome hands of these literary busy-bodies. All the same it is difficult to lay one’s hand on any particular verse or verses and assert convincingly that they are subsequent interpolations. The book, therefore, must be taken and judged as it is. Even as such, with the suspicious lurking in our minds that perhaps its original purity has been tampered with by the interested machinations and mental aberrations of some designing priest after it had left the hands of its noble author, its charms are irresistible and its beauty unsurpassed, provided it is never forgotten that it is a poem and a song first and an exposition of religious truths afterwards. It is this latter character of it which puzzles people. Some maintain that it teaches Advaitism, i.e., the existence of one entity only, viz., Brahman, whilst others hold that it teaches Dvaitavada, i.e., the co-existence of two entities, the human and the supreme soul. Surely there is enough in the text for either of these theories to be maintained with a show of reason. We are, however inclined to think that the collective weight of the whole poem favours the Dvaitavadis more than it does the Advaitavadis. Each party, of course, uses the full force of all the logic and argument they can command to explain away the verses that are quoted against them. Much ingenuity and erudition has been spent in these polemic discussions and some have been carried on with such nicety and subtlety of reasons as to perplex the ordinary reader, though they might charm the philosophical mind used to hair-splitting.

Then there is the divergence between the Sankhyas and the Yogis, the former being known as the Jnanakandis and the latter as Bhaktivadis and Karamkandis . The Sankhyas hold that the Gita establishes the superiority of jnana over all other ways of knowing an realizing the supreme soul, while the Yogis dispute it, and argue that the lord has given the foremost place to yoga and action, reducing all the different ways of approaching the Almighty to the one supreme principle of Yoga.

Then there is the divergence between the Sankhyas and the Yogis, the former being known as the Jnanakandis and the latter as Bhaktivadis and Karamkandis . The Sankhyas hold that the Gita establishes the superiority of jnana over all other ways of knowing an realizing the supreme soul, while the Yogis dispute it, and argue that the lord has given the foremost place to yoga and action, reducing all the different ways of approaching the Almighty to the one supreme principle of Yoga. If the language of the book is any guide to its subject, The message of the Bhagawad Gita surely the latter position seems to be the correct one. All the chapters of Gita end by giving a name to the principal topic expounded therein and every one of these names has the word yoga attached to it, such as the Sankhya yoga, the Karma yoga, the Sanyasa yoga and so on.

Then again there is another point on which there is an equally great difference of opinion, viz., the position of Krishna himself. The Sanatanists believe that he was an Avatar and spoke as if he and the supreme soul were identical. The Arya Samajists on the other hand dispute the doctrine of incarnation and say that Krishna never meant to claim divinity of himself, and that in very many places in Gita itself he speaks of himself as a human soul, as distinguished from the Divine and that in other places he only professes to speak in the name of God. Surely the latter position seems to be the correct one.

The disputants, however, in the eagerness of controversy and disquisition, entirely forgot that the discourse was never started the object of expounding any of these doctrines, its chief purpose being to persuade Arjuna to fight. Any one studying the book with care will see at once that throughout the eighteen discourses, the noble teacher never lost sight of his immediate object even for a moment. All that he did was use every kind of argument to convince Arjuna of the absurdity of his idea, of the unrighteousness of turning his back from the battle-field and giving way to a sentiment unworthy of a warrior, of the shamefulness of his abandoning a just cause and of the sinfulness of his being carried away by a false sentiment.In a masterly way he met all the objections of Arjuna and explained away the flaws which Arjuna found in his reasoning. But what is patent is, that in the intricacies of the logical expositions and in the labyrinth of dogma he never lets his immediate object slip out of his view. He returns to it again and again, appealing now to his sense of honour, then to his sense of duty and lastly to his reason. He goes further and quite in a human way calls his affection and regards for him into requisition. He overawes and frightens him. He claims confidence, devotion and obedience, and he succeeds. What he however maintains and expounds with all the vigour of language and earnestness of soul which he can command, is the supreme truth that, be the circumstances what they may, “Life is a mission and duty (dharma) its highest law”; that in the fulfillment of this mission and in the performance of his duty, lies the soul path to salvation or eternal bliss, that to the extent of one’s success in fulfilling this mission and in performing this duty will one ascend to the higher stage of life, which bring one nearer the goal, viz., the realization of the supreme soul and complete freedom from births or deaths, with the accompanying bliss . It is to this end that one has to make use of the Jnana, Karma, Sanyasa, Dhyana, Vijnana and different other forms of yoga enumerated therein. They are all means to an end, the immediate end being the fulfilling of the mission of one’s life leading to the ultimate one.

The mission of one’s life and its accomplishment , is also pointed out in the Gita. It is to be determined partly by the condition (including time and place) of one’s physical birth and partly by the condition of one’s real self, i.e., one’s soul. That life is a mission, is no new truth. That this mission is determined by the condition of one’s birth and soul. What particularly troubled Arjuna was whether it was not sinful to kill Drona, Bhishma, and others even when the performance of his duty (Dharma) required such slaughter? The reply of Krishna was that it was not. If in giving this answer he gave a dissertation on the immortality of the soul, providing that no one could really be killed, it was only by way of strengthening his argument. What he meant to say definitely is that one’s individual Dharma is the supreme law of his life, is the spring by which all its movements must be regulated. It is the rudder of the ship, the compass, the guiding star and the supreme determining entity. Everything else must be subordinated to it, put under its guidance and control as existing for it and for the furtherance of its end. The slaying of one’s nearest and dearest relative, not to speak of any enemy, is not sinful if one cannot perform one’s duty (Dharma ) but by slaying him. One’s dharma cannot be anything but righteous. Hence anything which is necessary to be done in the performance of Dharma cannot be sinful. A Raja commits no sin in punishing thieves, robbers, dacoits and murderers. A patriot warrior commits no sin in killing the enemies of his country in fair fight. No-body should jump to the conclusion, however, that the Gita justifies the killing of one’s adversaries or enemies at all times and on all occasions. As to the detailed rulers of the conduct in the keeping of one’s Dharma, the Gita refers us to the shastras. All that it lays down and lays down with emphasis and without the a shadow of doubt is, that-once you know your duty or your Dharma, you are not to be turned back from it by any consideration of self-interest, love or mercy. You are not required to sacrifice any of these if the performance of your duty does not call for such sacrifice. Where there is no doubt as to the righteousness of a certain course in the performance of your Dharma you are not to lightly justify the course which appears to you to be otherwise unrighteous. But if after weighing all the pros and cons and scanning it carefully in the light of your conscience and the teaching of Shastras, you conclude that you cannot do your duty without running the risk of doing what otherwise appears to you to be sinful, your path is clear, you must do the former at any risk and at any cost. No consideration of self interest, love, or mercy, no risk of calumny, pain and injury to self other should stand in the way of your duty. That is the lesson of the Gita in the nutshell. That is the burden of the song sung by Krishna on the field of Kurukshetra 5,000 years ago in order to turn his friend and disciple Arjuna away from the sinful inclination of his mistaken mind and to dispel the vapours of sentimental ignorance and false love that were encompassing him when standing face to face with his enemies, the enemies of his brother, the enemies of his king and the enemies of his country, viz., the troops of the tyrant and the usurper who had unjustly, unlawfully, by fraud, force and deceit deprived them of their just rights and established a reign of terror and sin.

This is the message of the Gita. Everything is only subsidiary to it and used as a means of elucidating and establishing this one truth. This is the pivot round which every arguments turns and this the sun round which all the planets with their satellites move. Let no one then confound what is only subsidiary with the central teaching. Of course every one of the various doctrines expounded or touched upon on the Gita has its own importance, every one of them has its own axis round which to move, everyone has its own light to shed, but the central sun of the whole system of the Gita is the truth that everyone must do his own duty, be true to his own Dharma, at any cost, at any risk and any sacrifice. It is exactly this that is meant by Sri Krishna when he says:

“Better one’s own duty (dharma) though destitute1 of merit, than the duty of another, well discharged. Better death in the discharge of one’s own duty; the of another is full of danger.” III. 35,

This couplet has nothing to do with creeds, doctrines and dogmas, although it is often cited as opposed to a change of religion and faith.It is not irreverent to say so, the argument seems to be more in the nature of a special pleading than a solemn and serious dissertation on religious doctrines.

The first chapter or the discourse describes the despondent state of Arjuna’s mind and is consequently called “Arjuna’s Vishada Yoga.” After giving a vivid description of the field battle and of what Arjuna said when with Krishna as his charioteer he was standing in the midst of two armies. The account is extremely pathetic, the more so, as the language employed is very simple and almost to a word similar to what every ordinary person in the world uses in a state of mind like what Arjuna is supposed to have been in at the time. Almost in a childlike way does Arjuna exclaim:-

“Seeing these my kinsmen, O Krishna, arrayed eager to fight, my limbs fail and my mouth is parched, my body quivers, and my hair stands on end, Gandiva slips from my hand and my skin burns all over. I am not ‘able to stand, my mind is whirling.’”

The nervousness that had taken possession of him is beautifully shown by making him say, “And I see adverse omens, O Krishna.” This is followed by philosophical questioning of the advantages that may be supposed to accrue by a successful ending of the war to his side. Adds Arjuna:-

“Nor do I see any advantages from slaying kinsmen arrayed in battle. For I desire not victory, O Krishna, nor pleasures, what is kingdom to us? O Govinda, what enjoyment, or even life? If those for whose sake we desire kingdom, enjoyments or pleasure stand here in battle, abandoning life and riches, teachers, fathers, sons, etc. Those I do not wish to kill, though myself slain, O Madhusudana, even for the sake of the kingship of the three worlds.”

Next is advanced the argument of the sin that is involved in the killing of the relatives and kinsmen, even though these latter “with intelligence overpowered, see no guilt in the destruction of family, no crime in hostility to friends.” Their ignorance in no way palliates the sin of those “who see the evil in destruction of family.”

In conclusion comes the argument which in Arjuna’s eyes appears to be the most conclusive and unanswerable, the subversion of family (“Kula”)-dharma and corruption and perversion of the family ties which must necessarily result from war.

Having argued this Arjuna concluded that he would rather slain by the sons of Dhritarashtra “unresisting and unarmed, in the battle,” than commit such a great sin himself. Having said so, he “sank down and on the seat of the chariot, casting away his bow and arrow, his mind overborne by grief.”

The second discourse opens with a touching and characteristic remonstrance by Krishna worthy of a warrior-prince typical of his times. Says he,

“Whence, O Arjuna, hath his ignoble dejection befallen thee, which is characteristic of the Anaryas (non-Aryas) and which is heaven-closing and infamous. Yield no impotence, O Partha! It doth not befit thee. Shake off this paltry faint-heartedness. Stand up, Parantapa (conqueror of foes)”

This is pre-eminently the language of a noble Kshattriya, of a man who knew what it meant for a Kshatriya to behave on a field of battle in the way proposed by Arjuna. The whole duty of an Arya-Kshatriya was summed in this pathetic reproach. In one pithy but beautiful sentence it pictured the infamy of the idea and its dismissal consequences. Strong language, indeed, but for the position and the authority of the man who used it with a sure and certain aim.

The dart, however, failed, and Arjuna retorted in a language more full of bitterness and depth of feeling than wisdom.

“How, O Madhusudana, shall I attack Bhishma and Drona, with arrows in battle, they who are worthy of reverence, O Slayer of foes? Better in this world to eat even the beggar’s crust than to slay these gurus high-minded. Slaying these gurus, our well-wishers, I should taste of blood-be sprinkled feasts.”

Having said this in anger, Arjuna regained himself immediately and proceeded to adopt an attitude which he thought was more befitting his relationship with the great Krishna, viz., one of a suppliant for knowledge, light and guidance.

“Nor know I which for us be the better, that we conquer them or they conquer us-these, whom having slain we should not care to live, even these arrayed against us, the sons of Dhritarashtra. My heart is weighed down with the vice of faintness5; my mind is affected with attachment in the matter of Dharma. I ask thee which may be the better7 – that tell me decisively. I am thy disciple , suppliant to thee; teach me. For I see not what would drive away this anguish that withers up my senses, if I should attain monarchy on earth without a foe, or even the sovereignty of the gods.”

Having this addressed Krishna he is reported to have finished off by saying “I will not fight.” Krishna, then undertook to lecture on the true philosophy of life and death, distinguishing the permanent, eternal and indestructible soul from the unpermanent, changing and decaying body. He began by pointing out that Arjuna was grieving “for those that should not be grieved for,” because, said he,

“At no time I was not, nor thou, nor these princes of men, nor verily shall we ever cease to be hereafter. As he dweller in the body (meaning the spirit) findeth in the body childhood, youth and old age, so passeth he on to another body *** the contacts of the senses *** giving cold and heat, pleasure and pain, come and go, unpermanent ***. The unreal hath no being; the real never ceaseth to be****. These bodies of the embodied One, who is eternal, indestructible and boundless, are known as finite. Therefore FIGHT, O BHARATA!”

However, he returns to the same argument and points out that

“He who reagrdeth this (i.e., the soul) as a slayer and he who thinketh he is slain, both of them are ignorant. He slayeth not, nor is he slain. He is not born nor doth he die, nor having been, ceaseth any more to be; unborn, perpetual, eternal and ancient, he is not slain when the body is* slaughtered**. How can that man slay, O Partha! or cause to be slain, him, whom he knoweth (to be) indestructible, perpetual, unborn, undiminishing. As a man casting off worn out garments, taketh new ones, so the dweller in the body (i.e., the soul) casting off worn out bodies entereth into others that are new. Weapons cleave entereth into others that are new. Weapons cleave him not, not fire burneth him, nor waters wet him, nor wind drieth him away; uneleavable he, incombustible he and indeed neither to be wetted nor dried away; perpetual, all-pervasive, stable, immoveable, ancient, unthinkable, immutable he is called; therefore knowing him as such thou shouldst not grieve.”

Thus ends Krishna’s first argument, which expounds the immortality and the indestructibility of the soul in stirring poetry. The expressions used have almost to a word been borrowed from the Upanishadas, but the poetry is the author’s own. The subject dealt with is, in certain respects, a very complex one, not to be easily followed in all its various bearings and lines of thought but the meaning and purport of the writer is quiet clear. It is sufficient to know here what Krishna evidently wanted Arjuna to understand, viz., that by killing the body he was not killing the real man embodied in the body, and latter was quiet distinct in the nature and the character from the former; the body being mortal and changeable, the soul being eternal, immortal and indestructible.

The second argument is based upon the inevitableness of death. The message of the Bhagawad Gita

“Or if thou thinkest of him,” continues Krishna, “as being constantly born and constantly dying, even then O! mighty armed, thou shouldst not grieve. For certain is death for the born and certain is birth from the dead. Therefore, over the inevitable thou shouldst not grieve.”

“Beings are unmanifest in their origin, manifest in their midmost state unmanifest likewise are they in dissolution: What room (is) then for lamentation?”

The argument is wound up by pointing out that marvelous as the soul of man appears to be, it is invulnerable and not a fit subject for grief.

The third argument is based on Arjuna’s individual “Dharma”.

“Further looking to your own dharma,” says Krishna, “thou shouldst not tremble; for there is nothing more welcome to Kshattriya than righteous war . Happy the Kshattriyas, O Partha, who obtain such a fight, unsought,9 offering as an open door to heaven.”

In the next four verses he points out the consequences of not fighting, saying:-

“But if thou wilt not carry on this righteous warfare, then destroying10 or outraging thy own dharma and (with it) thy honour, thou wilt incur sin. Men will recount thy dishonour (for all times to come11), and to one highly esteemed, dishonor exceedeth death. The great warriors (or charioteers, maharathi) will think thou fledst from the battle out of fear, and thou, that wast highly thought of by them, wilt be lightly held. Many unseemly words13 will be spoken by thy enemies, slandering thy strength. What (can be) more painful than that? Slain, thou wilt obtain heaven; victorious, thou wilt enjoy the earth; therefore, stand up, O son of Kunti, resolute to fight. Not minding pleasure and pain, gain and loss, victory and defeat, grid thee for the battle; (as) thou shalt incur no sin.”

The rest of this chapter with the argument, which is based upon the philosophy of Karma (action) without attachment to its fruits.

“Thy business is with the action only,” says Krishna, “never with its fruits; so let not the fruit of action be taken be thy motive; nor be thou to inaction attached. Perform action, O Dhananjaya, dwelling in union with the Divine, renouncing attachments and balance evenly in (i.e., without being distributed by) success of failure. This equilibrium is called yoga .”

In short the principle argument relied upon in the first part of the chapter based on the unborn and undying nature of human soul was in accordance with the Philosophy of Sankhya, but with the doctrine of karma began the teaching of yoga. In expounding this, Sri Krishna seems to speak of the karmakandis .

“Who with karma (desire) as the immediate object of the soul and heaven for its goal, offers birth, as the fruit of good action and lay too much stress on the ceremonies for the attainment of pleasure and lordship. Those who cling to pleasure and lordship and whose minds are captivated by such teachings (as lead to the same) are not endowed with that determined reason which is steadily bent on contemplation (Woe to the person) who cannot claim a determinate reason, such as is one-pointed, because many-branched and endless are the inclinations of one who possesses an indeterminate Buddhi.”

In verse 49 Krishna points out the inferiority of karma (action such as mentioned in 43) to Buddhiyoga and calls upon him to take refuge in the pure Buddhi.

“as pitiable18 are they who work for fruits. The Munis united to Buddhi renounces the fruit which action yeildeth and (thus) liberated from the bonds of birth, they attain the blissful state.”

Upon this Arjuna asked the Lord to explain what is distinguishing mark of him who is stable of mind and steadfast in contemplation.

“How doth the stable-minded, O Keshava, how doth he sit and how walk?”

Slokas 55 to 72 contain the answer to this question, which is, so to say, the Lord’s exposition of “Buddhi Yoga”.

“When a man abandoneth, O Partha, all the desires of the heart and is satisfied in the self by the self, then is he called stable in mind. He, whose mind is free from anxiety and pains, indifferent amid pleasures, loosed from passion, fear and anger, he is called a Muni of stable mind. He who on every side is without attachment, whatever hap of fair and foul, who neither likes nor dislikes, of such a one the understanding is well-poised19. The objects of sense turn away when rejected by an abstemious soul but still desire of them may remain. Even desires, however, is lost when the Supreme is seen. The excited senses of even a wise man carry away his mind, (though he may be striving hard to control them). (Therefore) having restrained them all, he should sit harmonized, devote wholly to me, 20 for of him the understanding is well-poised whose senses are mastered.

. It may be that he wanted to gain mastery over Arjuna thereby, or it may be a subsequent alteration, because the verses preceding and following it have no connection with the idea, and the argument is quite complete without it. The expression while quite intelligible in some other places in the poem, seems to be quite out of place here.

“Man, musing on the objects of sense, conceiveth an attachment to these; from attachment ariseth desire; from desire anger cometh forth; from anger proceedeth delusion; from delusion confused memory; from confused memory the destruction of Reasons; from destruction of Reasons , he perishes. But the disciplined self, moving among sense-objects with sense free from attraction and repulsion, mastered by the self, goeth to peace. In that peace the extinction of all pains ariseth for him, for of him whose heart is peaceful the Reason soon attaineth equilibrium. There is no pure Reason for the non-harmonised, nor for the non-harmonised is there concentration; for him without concentration there is no peace, and for the unpeaceful how can there be happiness? Such of the roving sense as the mind yeildeth to, that hurries away the understanding, just as the gale hurries away a ship upon the waters. Therefore, O mighty-armed, whose senses are all completely restrained from the objects of sense, of him the understanding is well-poised. That which is the night of all beings, for the disciplined man is the time of walking; when other beings are waking, then is it night for the muni who seeth. He attaineth peace, into whom all desires flow as river flow into the ocean, which is filled with water but remaineth unmoved- not he who desireth desires. Whose forsaketh all desires and goeth onwards free from yearnings, selfless and without egoism-he goeth to peace. This is Brahman state, O son of Pritha. Having attained thereto none is bewildered. Who, even at the death hour, is established therein, he goeth to the Nirvana of Brahman.”

So far the argument originally started has been completed. With a view to make Arjuna throw of his dejection and fight, Shri Krishna started first by rebuking him and charging him with ‘un-Ayranly,’ unmanly and ignoble conduct. When that failed to have its desired effect, he explained the delusion that underlay the idea of Arjuna’s incurring the sin of killing Drona and Bhishma, etc., by expounding the unborn and undying nature of the soul and declaring that it was the latter that was the real man and not the body which was changeable, transient and unpermanent. Then followed the inevitableness of death for every one born and vice versa. The fourth step was to exhort him to be true to his Dharma, regardless of consequences, and the fifth was asking him to perform Karma without attachment to its fruit. The last is in fact the governing principle of Gita, which has been explained, all through, time after time, in different forms, under different heads and with different arguments. “Act in the living present with unswerving loyalty to your Dharma, doing whatever is necessary for the performance thereof, with no fear of incurring sin, provided your acts are strictly actuated by a sense of duty and are not tainted by an attachment to the senses or to the mundane fruit of your actions,” is the sum-total of Krishna’s teachings to Arjuna. “Dharma” (duty) is the supreme law of life that alone leads one to salvation and the state of supreme bliss (paramananda), which is the goal of every human soul assuming a body and subjecting itself, in the language of the uninitiated, to recurring births and deaths. Everything else and every other consideration must be subordinated to and controlled by your Dharma. All your energies and powers must be concentrated on that point. That must be center of your system. There is no going off and on. In the pilgrimage of your life you are successful in proportion as you have found out your Dharma and stood to it. The day you approach the highest rung in the ladder of your Dharma, you have crossed the ocean of life, got rid of the births and deaths and reached your heaven. Then you enjoy a state of perfect bliss. If on the other hand you betray your Dharma; if you are carried away from it by other considerations, viz., your own conceptions of virtues and vice, pleasure and pain, truth and falsehood; if you fail to stand to your duty and make it the rule of life under all circumstances, favourable or unfavourable; and if you allow yourself to be guided by wrong ideas and false sentiments, you are surely on the road that leads to destruction. By such a course you only deepen the whirlpool and enhance the fury of the storm wherein the frail bark of the life of your soul is being tossed up and down, forward and backward, without a way out, without a star in the horizon to cheer it up in the hour of its difficulty, and without a hope of its ever reaching the harbour of safety.

The all subsequent chapters are in a way only an amplification of Karmayoga. The mixing up of Buddhi yoga and Karmayoga, however, and certain other expressions about the supreme excellence of determinate reason, created some confusion in the mind of Arjuna and consequently in the two verses of the third chapter he begs for the clearing up of the doubt. Addressing Krishna he says,

“If it be thought by thee that knowledge is superior to action, O Janardana, why dost thou, O Kesava, enjoin on me this terrible action (i.e., war)? With these perplexing words thou hast only confused my understanding; tell me, therefore, with certainty the one way by which I may reach bliss.”

The lord replied, “In this world there is a two-fold path, as I said before, O sinless one: that of Yoga by knowledge of the Sankhyas: and that if Yoga by action of the Yogis. Man winneth not freedom from action by abstaining from activity, nor by mere renunciation doth he rise to perfection, nor can any one, even for instant remain really actionless; fro helplessly is every one driven to action by the energies born of nature. Who sitteth, controlling the organs of action but dwelling in his mind on the objects of senses, that bewildered man is called a hypocrite. But who controlling the senses by the mind O Arjuna, with the organs of actions without attachment, performeth yoga by action (he is worthy.”

“Perform thou right action, for action is superior to inaction, and inactive, even the maintenance of thy body would not be possible. The world is bound by action, unless performed for the sake of sacrifice ; for that sake, free from attachment, O son of Kunti, perform thou action. Having in ancient times emanated mankind together with sacrifice, the Lord of emanation said: ‘By this shall ye propagate; be this to you the giver of desires; with this nourish ye the gods, may the gods nourish you; thus nourishing one another, ye shall reap the supremest good. For, nourished by sacrifice, the gods shall bestow on you the enjoyments you desire.’ A thief verily is he who enjoyeth what is given by Them without returning Them aught. The righteous, who eat the remains of the sacrifice, are freed from all sins; but the impious, who dress food for their own sakes, they verily eat sin. Food from creatures become; from rain is the production of food; rain proceedeth from sacrifice; sacrifice ariseth out of action; know thou that from Veda action groweth, and Veda from the Imperishable cometh. Therefore Brahman, the all-permeating, is ever present in sacrifice. He, who the earth doth not follow the wheel thus revolving, sinful of life and rejoicing in the senses, he, O son of Pritha, liveth in vain.” ( verses 3-16, ch. III)

Verses 10-14 explain which is meant by yajna, which is translated by the word sacrifice, though it hardly gives the whole or correct idea of yajna. In verses 12 and 13 rather strong language is used in denouncing those selfish people who act with the sole purpose of self-enjoyment, without any idea of Dharma or Karma. But this is only by the by. Verses 14 and 15 reproduce the idea which is very common in ancient Aryan literature, tracing the hand of god in every righteous action enjoined by the Vedas; while verse 16th emphatically lays down the consequences of neglecting them. Verses 17th and 18th are again puzzling and conclude in the language of riddles but the 19th is very clear and concludes the reasoning in the verses 3 to 16. “Therefore, without attachment, constantly perform action which is duty, for by performing action without attachment, man verify reacheth the supreme.” With verse 20 begins another link in the chain of Krishna’s persuasive armoury. Citing the example of Raja Janak (a highly respected name in Hindu theological literature), he tells Arjuna that having an eye to the protection of the masses also, he should perform action. He explains what he means, in verses 21 to 26:-

“Whatsoever a great man doeth, that other men also do; the standard he sitteth up, by that the people go. Here is nothing in the three worlds, O Partha, that should be done by me, nor anything unattained that might be attained; yet I mingle in action. For if I mingled not ever in action unwearied, men all around would follow my path, O son of Pritha. These worlds would fall into ruin, if I did not perform action; I should be the author of confusion of castes, and should destroy these creatures. As the ignorant act from attachment to action, O Bharata, so should the wise act without attachment, desiring the maintenance of mankind. Let no wise man unsettle the mind of ignorant people attached to action; by acting in harmony with me let him render all action attractive.”

In verse 27 another argument is advanced, viz., that “all actions are wrought by the energies of nature only; the self-deluded by egoism thinketh: ‘I am the doer.’” Verses 28 an d29 repeat the non-attachment to the fruits of action is the sign of perfect knowledge, the professor of which is exhorted not to unsettle the minds of those whose knowledge is imperfect. In conclusion the lord calls upon Arjuna to surrender all actions to Him in all sincerity to heart and to engage in battle, giving up all hope and attachment and cured of mental fever. Verses 31 and 32 are an attempt to inspire faith in His teaching.

“Who abide ever is this teaching of mine, full of faith and free from caviling, verily they are released from actions. But those who carp at my teaching and act not thereon, senseless, deluded in all knowledge, know thou them to be given over to destruction.”

Verse 35 gives the finishing touch by once more alluding to Arjuna’s own Dharma (duty) as a Kshattriya (warrior) and by holding up the danger-signal against the temptation of attempting to assume the duties (Dharma) of a different class. “Better death in the discharge of one’s own duty; the duty of another is full of danger.” Thus ends the masterly argument of Krishna. What follow are replies to question put by Arjuna, elucidating the different points that had indirectly and collaterally arisen in the course of the above argument. These replies involved learned expositions of several knotty points of doctrinal philosophy, but, in reality they are neither material to nor important for, the main purpose of the dialogue. But there are plenty of indications all through, that the latter is never dropped. Chapter III concludes with an explanation of the origin of sin in answer to Arjuna’s query, viz., “dragged on by what does a man commit sin, reluctantly, indeed, as it were by force constrained?” In chapter IV is discussed the philosophy of births and deaths, with a sermon on the nature, essence and kinds of sacrifices. The chapter, however, winds up with an exhortation to fight, in the last verse, which runs thus:-

“Therefore with the sword of wisdom of the self , cleaving asunder this ignorance-born doubt, dwelling in thy heart, be established in Yoga. Stand up, O Bharata.”

Chapter V begins with a question by Arjuna as to which of the two, “Renunciation of activities’ ‘Yoga’, is the better and more approved path. In the very next verse Lord gives a decisive opinion in favour of ‘Yoga by action’ in preference of ‘Renunciation of activities’.’ The rest of the discourse is a detailed discussion of “Sannyasa Yoga” followed by an equally masterly exposition of ‘Yoga by meditation’ in the VIth Chapter.Chapter VII to XVI both inclusive contain the poetry of the book. From the doctrinal point of view, the subject is practically the same but the language and the sentiments constitute sublime poetry and divine music. To the language of philosophy and that of science, in explaining the mystery of life and death, are added the charm of expression and the freedom of flight on the wings of the imagination. Riddles are explained away by riddles. The solutions are as perplexing as the problems. All reserve is set aside and the most complex and difficult of questions are met with the greatest boldness and in a tone of absolute confidence and unswerving faith in self. It, is as if, talking of serious matters in the language of disquisition, the writer suddenly remembers that he is composing music and writing poetry and not a book on polemics. Seemingly forgetful of the actual object in view, he transports himself to the vastness of the limitless space and lets his imagination go free. Absorbed in the beauty of his own expanded soul he sees nothing but beauty and harmony in this universe, nay, even beyond and out of it.

Considered from the point of view of the original object of the dialogue, it is a most daring and successful effort to over-awe Arjuna as well as to inspire him with confidence and faith in the wisdom of Krishna and in his to elicit implicit obedience to his will. It is an appeal to fear, love, respect, and admiration all combined, and wound up with the supreme authority of the Shastras. The concluding verses of the XVIth chapter lay down that“he who, having cast aside the ordinances of the shastras, following the promptings of desire, attaineth not to perfection, nor happiness, nor the highest goal. Therefore, let the Shastras be thy authority in determining what ought not to be done. Knowing what hath been declared by the ordinances of the Shastras, thou oughtest to work in this world.”

The reason for reference to the authority of the Shastras as regards the Duty of Arjuna is clear enough.

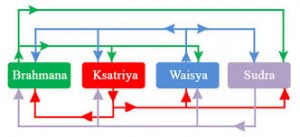

In chapter XVII is explained, in reply to a question to Arjuna, the condition of a man who sacrifices with faith but casting aside the ordinance of the Shastras. This leads to a discourse on sacrifices, followed by a disquisition on the essence of ‘Renunciation’ and ‘Relinquishment’ in chapter XVIII. In this last discourse, is practically recapitulated the substance of the whole teaching of Gita in a rather simple form, with special reference to the action of the three Gunas (energies), Sattva, Rajas and Tamas, because there is not an entity, according to Krishna, either on this earth or in heaven among the Gods that is free21 from these three qualities born of matter. Then is described the distribution of duties according to the qualities born of their own natures amongst the four principal castes, viz., Brahmans, Kshattriyas, Vaishyas and Sudras , every one reaching perfection by his being intent on his karma .

The next verse points out that a man winneth perfection by worshipping Him from whom all beings emanate and by whom everything is pervaded, in his own duty ; from which it only naturally follows that;

“one’s own duty is better though destitute of merits that the well-executed duty of another22; he who doeth the karma laid down by his nature incurreth no sin.”

Stress is again laid upon the same idea by saying that “nature-born karma, though defective, ought not to be abandoned (as) all undertakings indeed are clouded by defects as fire by smoke.” Through the masterly ingenuity with which repeated appeals are being made to Arjuna in the name of his Kshattriya Dharma. The language used is very guarded. A distinction is made in the different verses between Dharma and Karma,23 which is not very clear. The words, “destitute of merit” and “defective” are evidently used in a comparative sense to denote the superior merit and eventual excellence of the Brahman’s Dharma and Karma as compared with those of a Kshattriya. All the same the latter is clearly and unambiguously enjoined not to neglect his own. Not only does he incur no sin by performing his own duty but that is only way for him to wash off his previous sins, and improve his nature in order to gain the next step; verses 49 to 53 pointing out the way ‘ to be fit to become a Brahman.’ Even a Brahman, however, is not free from the obligation to perform karma, though over and above that, he must take refuge in the Lord, as it by His that he attaineth the eternal indestructible abode. Speaking on behalf of the Lord, in the first person singular, Krishna takes particular care not to let Arjuna elude obedience to his wishes. He says:-

“Renouncing mentally all works in Me, intent on Me, resorting to the Yoga of discrimination , have thy thought ever on Me. Thinking of Me thou shalt overcome all obstacles by my grace: but if from egoism thou shalt not listen, thou shalt be destroyed utterly. Entrenched in egoism thou thinkest, ‘I will not fight’; to no purpose thy determination; nature will constrain thee. O son of Kunti, bound by thine own Karma, born of thine own nature, that which from delusion thou not to do, even that helplessly thou shalt perform. Ishwara dwelleth in the hearts of all beings, O Arjuna, by His Maya causing all beings to revolve, as though mounted on a potter’s wheel. Flee unto Him for shelter with all thy being, O Bharata; by His grace thou shalt obtain supreme peace, the ever-lasting dwelling place.”

It will be ridiculous to take very word literally, as, in that case the analogy of the potter’s wheel will destroy all freedom of action on the part of man, which is far from Krishna’s mind. The net of logic, philosophy, reason and faith which Krishna so skillfully and so ingeniously wove round Arjuna’s heart and brain, could not fail to have its effects. Arjuna’s doubts were completely annihilated and having been entirely subdued he gave in. Says Arjuna at last,

“Destroyed is my delusion. I have gained knowledge through Thy grace, O Achyuta. I am firm, my doubts have fled away. I will do according o Thy word.”

So did Krishna triumph, and verily “Where ever is Krishna, Yoga’s Lord, and wherever is Partha, the Archer assured are there prosperity, victory and happiness.

In short let us invoke his aid by acting up to his message and we are sure all our doubts will be dispelled, our unmanliness gone and the road to success and glory gained but surely. It will a shame if the countrymen of Krishna let any false ideas of Yoga prevail amongst them or let any false doctrines of renunciation and relinquishment enfeeble their arms.

REFERANCES

LAJPAT RAI: THE BHAGAWAD GITA. THE INDIAN PRESS ALLAHABAD . 1908