Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Jonathan Kozol

Education is a tri-polar process, in which on the one end is the teacher ,on the second is the student and on the third is the curriculum. Curriculum refers to the means and materials with which students will interact for the purpose of achieving identified educational outcomes. In fact ,the curriculum is that mean which forms the basis of the educational process. If education is accepted as the teaching-learning process, then both teaching and learning take place through the curriculum.

The term ‘curriculum ’has been derived from a Latin word ‘currere’ which means race course .Thus ,the term ‘curriculum’ has the sense of competition and achievement of goal inherent in it. It is said that the curriculum consists of all the planned experiences that the school offers as part of its educational responsibility, but curriculum includes not only the planned, but also the unplanned experiences as well.

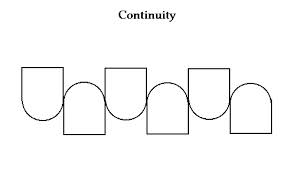

Another point of view suggests that curriculum involves organized rather than planned experiences because any event must flow of its own accord, the outcome not being certain beforehand.

Curriculum is total environment. The most comprehensive concept of curriculum is given by those who conceive it to include the total environment of the school. In fact, the curriculum has been described as “the environment in motion.” In modern times, the term is interpreted in this more liberal sense because there is no questioning the fact that the child’s education is influenced, by not only books but the playground, library, laboratory, reading room, extra-curricular programmes, the educational environment, and a host of other factors. In the school, both the educator and the educand are part of the curriculum because they are part of the environment. Actually the curriculum is only that part of the plan that directly affects students. Anything in the plan that does not reach the students constitutes an educational wish, but not a curriculum. Half a century ago Bruner (1960) wrote, “Many curricula are originally planned with a guiding idea . . . But as curricula are actually executed, as they grow and change, they often lose their original form and suffer a relapse into a certain shapelessness”

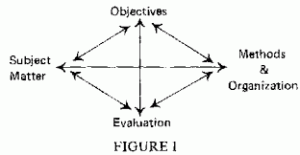

Basic Components of Curriculum:

Organised form of subject-matter,. Curriculum is the organized form of subject-matter, specially prepared to experiences and activities which provide the student with the knowledge and the skill he will require in facing the various situations i of real life. Obviously, the term ‘curriculum’ cannot be restricted to ; list of books, because it must include other activities which provide [the student with the knowledge and the skill he will require in facing [the various situations of life, meet the requirement of children. Hence, Snow curriculum includes those environment of the schools and numerous other elements not taught by books. In the words of Bent and Kronenburg , “Curriculum, in its broadest sense, includes the complete school environment, involving all the courses, activities, reading and associations furnished to the pupils in the school.”

Curriculum is comprehensive experience. In the words of Munroe, “Curriculum embodies all the experiences which are utilized by the school to attain the aims of education.” Thus, the various subjects included for study in a curriculum are not intended merely for study or rote learning but to convey experiences- of various kinds .Curriculum does not mean only the academic subject traditionally taught it the school, but it includes the totality of experiences that a pupil receives through the manifold activities that go on in the school in the classroom, library laboratory, workshop, playground and in the numerous informal contacts between teachers and pupils.

The curriculum includes all the learner’s experiences in or outside school which has been devised to help him develop mentally, physically, emotionally, socially, spiritually and morally.” it is obvious, then that, the aim of curriculum is to provide experience to the educand so that he may achieve complete development. By calling the curriculum an experience, the fact is made explicit that it includes not merely books, but all those activities and relationship which are indulged in by the educand, both inside and outside the school

Curriculum is not an end in itself, but a means to an end. Curriculum Is a means or tool. It is apparent from the foregoing definitions that because it is created – in order to achieve the aims of education. That is why, one finds that different educationists have suggested different kinds of curricula to conform to the aims and objectives ascribed to education; Explaining the concept of curriculum as a tool of education, Cunningham writes, “The curriculum is the tool in the hands of the artist (the teacher) to mould his material (the pupil) according to his ideal (objective) in his studio (the school).” Here the educator is compared to an artist and the curriculum as one of the instruments of tools used by him to develop the educand according to, and in conformity with the aims of education. It is evident that the curriculum will change with every change -in the aims of education.

“The curriculum may be defined as the totality of subject ‘matter, activities, and experience which constitute a pupil’s school life.” Curriculum includes all activities Elaborating the same concept further, H.H. Horne says, “The curriculum is that which the pupil is (aught. It involves more than the acts of learning and quiet study, it involves occupations, production, achievements, exercise, activity. “Pragmatists, too, have included the entire range of the educand’s activities in the curriculum because according to them, the child learns by doing. In the light of the various definitions of curriculum given it is possible to arrive at a definition of the term which includes all the points mentioned in these definitions. Briefly, then, curriculum is the means of achieving the goals of education . It includes all those . experience activities and environments which the educand receives during his educational career. Such a definition of curriculum comprehends the edueand’s entire life, a contention borne out by all modern educationists who believe that .the child learns not only inside the school, but also outside it, on the playground, at home, in society, in fact, every where. That is why, there is nowadays so much insistence on the participation of the parents in the child’s education and on not restricting the environment of the curriculum to the school environment but taking it means every possible kind of environment encountered by the child. Besides, it includes all those activities which the child does, irrespective of the time and place of these activities. It also includes the entire range of experiences that the child has in the school, at home, in the world at large. Considering from his liberal standpoint, one finds that is preparing the curriculum one has much wider background than would otherwise be possible.

The Purpose of Curriculum

The purpose of the curriculum is to prepare the student to thrive within the society as it is—and that includes the capacity for positive change and growth .Clarifying the purpose of curriculum, it has been pointed out in the report of the Secondary Education Commission( 1952-53 India) that, “The starting point for curricular reconstruction must, therefore, be the device to bridge the gulf between the school subjects and to enrich the varied activities that make up the warp and woof of life.” Hence, the curricular should be so designed that it strains the educand to face the situations of real life, a curriculum can be said to have the following major purposes

Synthesis of subjects and life. The aim of the curriculum is to arrange and provide those subjects For an edueand’s study which will enable the educand to destroy any gulf between school life and life outside the school. The opinion of the Secondary Education Commission has already been quoted.

Harmony between individual and activity. In a democracy, such social qualities as social skills, cooperation, the desire to be of service, sympathy, etc., are very significant because without them, no society can continue to exist. On the other hand, development of the individual’s own character and personality arc also very important. Hence, the curriculum must create an environment and provide those books which enable the individual to achieve his own development at the same time as he learns these social qualities.

Development of democratic values. In all democratic countries, the curriculum of education must aim to develop the democratic values of equality, liberty and fraternity, so that the educands may. develop into fine democratic citizens. But the development should not only aim at national benefit. The curriculum must also aim to introducing a spirit of internationalism in the cducand.

Satisfaction of the educand’s need. In defining curriculum, many educationists have insisted that it must be designed to satisfy the needs and requirements of the educand. It is seen that one finds a great variety of interests, skills, abilities, attitudes, aptitudes,’ etc., among educands. A curriculum, should be so designed as satisfy the general and specific requirements of the educands.

Realization of values. One aim of education is development of character, -and what is required for this is to create in the educand a faith in the various desirable values. Hence, one of the objectives of education is to create in the educand a definite realization of the prevailing system of values.

Development of knowledge .and Addition to knowledge In its most common connotation, the term curriculum is taken to mean development of knowledge or acquisition of facts and very frequently, this is the aspect kept in mind while designing a curriculum. But it must be remembered that it is not the only objective, although it is the most fundamental objective of a curriculum.

. In the contemporary educational patterns that curriculum is believed to the suitable which can create a harmony between the various branches of knowledge so that the educand’s attitude should be comprehensive and complete, not one sided.

Creation of a useful environment. Another objective of curriculum is to create an environment suitable to the educand. Primarily the environment must assist the educand in achieving the maximum possible development of his facilities, abilities and capabilities.

Principles of Curriculum Construction

Different educationists have expressed their own views about the fundamental principles of curriculum construction, the difference being created by their different philosophies of education. Briefly, the main principles of curriculum construction are the following:

Principle of utility. T.P. Nunn, the educationist, believes that the principles of utility is the most important principle underlying the formation of a curriculum. He writes, “While the plain man generally likes his children to pick up some scraps of useless learning for purely decorative purpose, he requires, on the whole, that they shall be taught what will be useful to them in later life, and he is inclined to give ‘useful’ a rather strict interpretation.” As a general rule, parents are in favour of including all those subjects in the curriculum which are likely to prove useful for their child in his life, and by means of which he can be fade a responsible member of society.

Principle of Training in the proper patterns of conduct. According to Crow and Crow, the main principle underlying the construction of a curriculum is that, through education the educand should be able to adopt the patterns of behavior proper to different circumstances. Man is a social animal who has to constantly adapt himself to the social environment. Therefore, education must aim at developing all these qualities in the educand which will facilitate this adaptation to the social milieu. The child is by nature self-centered, but education must tech him to attend the needs and requirements of others besides him. One criterion of an educated individual is that he should be able to adapt himself to different situations with which he is comforted. In his context, the term conduct must be understood in its widest sense. Only then can this principle of curriculum construction be properly understood. “All our activities in social, economic, family and cultural environment constitute behavior or conduct, and it is the function of education of teach us how he behaves in different situation.”

Principle of Synthesis of play and work. Of the various modern techniques of education, some try to educate through work and others through play. But a great majority of educationists agree that the curriculum should aim at achieving a balance between play and work. In other words, the work given to the educand should be performed in such a manner that the child may believe it to be play. There is a difference between work and play. That is why, parents want to engage the child in work instead of allowing him to play all the time, but the child is naturally inclined to spend his time in playing. Keeping this in view, T.P. Nunn has written, “The school should be thought* of not as a knowledge-monger’s shop, but a place where the young a-e disciplined in certain forms of activity. All subjects should be laugh; in the ‘play way’ care being taken that the ‘way’ leads continuously from the irresponsible frolic of childhood to the disciplined labors of manhood.”

Principle of Synthesis of all activities of life. In framing a curriculum, attention should be paid to the inclusion, in it, of all1 the various activities of life, such as contemplation, learning, acquisition of various kinds of skill, etc. In the individual and social sphere of life, every individual has to perform a great variety of activities, and this success in life is determined by the success of all these activities. ‘Hence, the curriculum should not neglect any form of activity related to any aspect of life. A curriculum constructed on this basis will be both comprehensive and closely related to life. In other words, it should include all the activities that educand is likely to require in later life.

Principle of individual differences. Modern educational psychology has brought to light, and stressed the significance of individual differences that exist between one individual and another. It has been discovered that people differ in respect of theft mental processes, interests, aptitudes, attitudes, abilities, skills, etc., and these differences are innate. All modern education is paid centric that is, it is centered on the ‘child. Psychologists insist that the curriculum should be so designed as to provide an opportunity for complete and comprehensive development to widely differing individuals. One of the basic qualities of such a curriculum is flexibility; for it must be flexible, in order to accommodate, educands of low, verge or high intelligence and ability, and to provide each one a chance to develop all his the greatest possible extent.

Principle of Constant development. Another basis for curriculum construction is the principle o a dynamic curriculum, based on the realization that no curriculum can prove adequate for all times and in all Places. For this reason, the should be flexible and changeable. This is all the more true in the modern context when new discoveries in the various branches of science are taking place everyday. Hance, it becomes necessary to reshape the curriculum fairly, frequently in order to incorporate the latest development.

Principle of Creative training. Another important principle of curriculum construction is that of creative training. Raymont has correctly stated that a curricuhm appropriate for the needs of today and the future must definitely have a positive bias towards creative subjects. And, one of the aim of education is to develop the creative faculty of the educand. All that is finest in human culture is the creation of man’s creative abilities. Children differ from other in respect of this ability. Hence, in franking a curriculum, attention must be paid to the fact that it should encourage each educand to develop his creative ability as far as is possible.

Principle of Variety. Variety is another important principle of curriculum construction. The innate complexity make it necessary that the .curriculum should be valid, because no one kind of curriculum can develop all to facilities of an individual. Hence, at every level the curriculum rust have variety, it will, on the one hand, provide an opportunity development of the different faculties of the educand, while on the other, it will retain his interest in education.

Principle of Education for leisure. One of the objective ascribed to education is training fr leisure, because it is believed that education is not merely for employment or work. Hence, it is desirable that the curriculum should also include a training in those activities which will make the individual’s leisure more pleasurable. A great variety of social, artistic and sporting activities can be included in this kind of training., Brides, educands should be encouraged to foster some of the other besides, so that they can put their leisure to constructive and pleasant use.

Principle of Related to community life. Curriculum can also be based on the principle that school and community life must be intimately related to each there. One cannot forget that the school is only a miniature form of immunity. Hence, the school curriculum should include all those activate which are performed by members of larger community outside the’ boundaries of the school. This will help in evolving social qualities for the individual, in developing the social aspect of his personal band finally, in helping his final adaptation to the social environs & into which he must ultimately go.

Principle of Evolution of democratic values. The construction of a curriculum in a democratic society is conditioned by the need to develop democratic qualities in the individual. The curriculum should be, so dogged that it develops a democratic feeling and creates a positive £h in democratic values. The progrmmes devise in the college qualities the educand so that he may be able to participate usefully and successfully in democratic life. In all the democratic societies of the wool this is the chief consideration in shaping the curricula for primary, secondary and higher education.