Dr. V.K.Maheshwari M.A. (Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D.

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Mrs Sudha Rani Maheshwari, M.Sc (Zoology), B.Ed.

Former Principal. A.K.P.I.College, Roorkee, India

Human beings will be happier – not when they cure cancer or get to Mars or eliminate racial prejudice or flush Lake Erie but when they find ways to inhabit primitive communities again. That’s my utopia.

Kurt Vonnegut

The first and foremost is to define the concept of beauty. From the lay-man point of view ,beauty is the effect one feel after receiving or perceiving any stimulus, concrete or abstract. This effect can be pleasing or repulsive. We shall answer, briefly and precariously, that beauty is any quality by which an object or a form pleases a beholder. Primarily and originally the object does not please the beholder because it is beautiful, but rather he calls it beautiful because it pleases him.

Any object that satisfies desire will seem beautiful. The pleasing object may as like as not be the beholder himself; in our secret hearts no other form is quite so fair as ours, and art begins with the adornment of one’s own exquisite body. Or the pleasing object may be the desired mate; and then the aesthetic beauty-feeling sense takes on the intensity and creativeness of sex, and spreads the aura of beauty to everything that concerns the beloved one to all forms that resemble her, all colours that adorn her, please her or speak of her, all ornaments and garments that become her, all shapes and motions that recall her symmetry and grace. Or the pleasing form may be a desired male; and out of the attraction that here draws frailty to worship strength comes that sense of sublimate satisfaction in the presence of power which creates the loftiest art of all.

Finally nature herself with our cooperation may become both sublime and beautiful; not only because it simulates and suggests all the tenderness of women and all the strength of men, but because we project into it our own feelings and fortunes, our love of others and of ourselves relishing in it the scenes of our youth, enjoying its quiet solitude as an escape from the storm of life.

Actually the above point refers only about the effect of beauty, but” what” aspect of the basic question is still unanswered. Actually beauty is nothing but an equilibrium among the various inherent components in anything, may it be music. Painting, literary work , a thought in philosophy or anything in nature including biological structure or social and cultural impact factors.

Another problem area is determining the nature of beauty, is it subjective or object oriented/ objective? The supporters of subjective nature give some significant arguments like,” for the mother, her child is the most beautiful child” or “ why we feel attracted towards one person in one situation and for the same person we may feel the opposite in different situation”

The supporters of the object oriented view argue like, “The sculptures of Ajanta cave , paintings of Leonardo , classical music, or poetry of Rabindra Nath Tagore are beautiful ,if you fail to appreciate them , it is due to your ignorance . So the fault lies in you not in the object.

Both types of arguments carry weight. So it can be concluded that the nature of beauty is both subjective as well as object- centred/ objective.

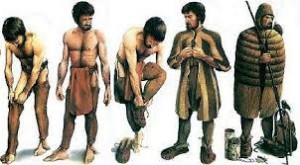

The primitive sense of beauty

Primitive man seldom thinks of selecting women because of what we should call their beauty; he thinks rather of their usefulness, and never dreams of rejecting a strong-armed bride because of her ugliness. The Red Indian chief, being asked which of his wives was loveliest, apologized for never having thought of the matter. “Their faces,” he said, with the mature wisdom of a Franklin, “might be more or less handsome, but in other respects women are all the same.” Where a sense of beauty is present in primitive man it sometimes eludes us by being so different from our own.

“All Negro races that I know,” says Reichard, “account a woman beautiful who is not constricted at the waist, and when the body from the arm-pits to the hips is the same breadth ‘like a ladder,’ says the Coast Negro.” Elephantine ears and an overhanging stomach are feminine charms to some African males; and throughout Africa it is the fat woman who is accounted loveliest.

“Most savages says Briffault, “have a preference for what we should regard as one of the most unsightly features in a woman’s form, namely, long, hanging breasts.” “It is well known,” says Darwin, “that with many Hottentot women the posterior part of the body projects in a wonderful manner . . .; and Sir Andrew Smith is certain that this peculiarity is greatly admired by the men. He once saw a woman who was considered a beauty, and she was so immensely developed behind that when seated on level ground she could not rise, and had to push herself along until she came to a slope. . . .According to Burton the Somali men are said to choose their wives by ranging them in a line, and by picking her out who projects furthest a tergo. Nothing can be more hateful to a Negro than the opposite form.” 88 In Nigeria, says Mungo Park, “corpulence and beauty seem to be terms nearly synonymous. A woman of even moderate pretensions must be one who cannot walk without a slave under each arm to support her; and a perfect beauty is a load for a camel.”If the sense of beauty is not strong in primitive society it may be because the lack of delay between sexual desire and fulfilment gives no time for that imaginative enhancement of the object.

Clothing

Clothing was apparently, in its origins, a form of ornament, a sexual deterrent or charm rather than an article of use against cold or shame. The Cimbri were in the habit of tobogganing naked over the snow. When Darwin, pitying the nakedness of the Fuegians, gave one of them a red cloth as a protection against the cold, the native tore it into strips, which he and his companions then used as ornaments; as Cook had said of them, timelessly, they were “content to be naked, but ambitious to be fine.”" In like manner the ladies of the Orinoco cut into shreds the materials given them by the Jesuit Fathers for clothing; they wore the ribbons so made around their necks, but insisted that “they would be ashamed to wear clothing’” An old author describes the Brazilian natives as usually naked, and adds: “Now alreadie some doe weare apparell, but esteem it so little that they weare it rather for fashion than for honesties sake, and because they are commanded to weare it; … as is well scene by some that sometimes come abroad with certaine garments no further than the navell, without any other thing, or others only a cap on their heads, and leave the other garments at home.”" When clothing became something more than an adornment it served partly to indicate the married status of a loyal wife, partly to accentuate the form and beauty of woman. For the most part primitive women asked of clothing precisely what later women have asked not that it should quite cover their nakedness, but that it should enhance or suggest their charms. Everything changes, except woman and man.

The Cosmetic painting of the body-

Body painting is a form of art that followed us from the ancient prehistoric times when human race was born, to the modern times where artist use human body as a innovative canvas that can showcase human beauty like no art style before it. Many believe that body painting was the first form of art that was used by humans, and archaeological evidence is close to support it.

Records of various ancient and modern tribes from Africa, Europe, Asia and Australia show clear records of their body painting heritage. By using natural pigments from plants and fruits, ancient people decorated themselves with ritual paintings, tattoos, piercings, plugs and even scarring. According to many historians, body painting was the important part of the daily and spiritual lives, often showcasing their inner qualities, wishes for future, images of gods, and many natural or war themes. There, body paint was often applied for weddings, preparations for war, death or funerals, showcasing of position and rank, and rituals of adulthood. In addition to temporary body paints, many cultures used face paint or permanent tattooing that could showcase much larger details than paintings made from natural pigments.

Indeed it is highly probable that the natural male thinks of beauty in terms of himself rather than in terms of woman; art begins at home. Primitive men equalled modern men in vanity, incredible as this will seem to women. Among simple peoples, as among animals, it is the male rather than the female that puts on ornament and mutilates his body for beauty’s sake. In Australia, says Bonwick, “adornments are almost entirely monopolized by men”; so too in Melanesia, New Guinea, New Caledonia, New Britain, New Hanover, and among the North American Indians. In some tribes more time is given to the adornment of the body than to any other business of the day.

Apparently the first form of art is the artificial colouring of the body sometimes to attract women, sometimes to frighten foes. The Australian native, like the latest American belle, always carried with him a provision of white, red, and yellow paint for touching up his beauty now and then; and when the supply threatened to run out he undertook expeditions of some distance and danger to renew it. On ordinary days he contented himself with a few spots of colour on his cheeks, his shoulders and his breast; but on festive occasions he felt shamefully nude unless his entire body was painted.

In some tribes the men reserved to themselves the right to paint the body; in others the married women were forbidden to paint their necks. But women were not long in acquiring the oldest of the arts cosmetics. When Captain Cook dallied in New Zealand he noticed that his sailors, when they returned from their adventures on shore, had artificially red or yellow noses; the paint of the native Helens had stuck to them.” The Fellatah ladies of Central Africa spent several hours a day over their toilette: they made their fingers and toes purple by keeping them wrapped all night in henna leaves; they stained their teeth alternately with blue, yellow, and purple dyes; they colour their hair with indigo, and pencilled their eyelids with sulphuret of antimony.” Every Bongo lady carried in her dressing- case tweezers for pulling out eyelashes and eyebrows, lancet-shaped hair- pins, rings and bells, buttons and clasps.

Tattooing, scarification

Scarification is a permanent procedure meant to decorate and beautify the body.Artists used the body as their canvas and the results became socially valuable. The operation of cutting and raising scars was common, as ‘tattooing’ was not an effective way to decorate dark pigmented skins.The process of African scarification involved puncturing ‘or cutting’ patterns and motifs into the epidermis of the skin. Different tools produced different types of scars, some subtle, others profound. Scarification served as a symbol of strength, fortitude and courage in both men and women. Scars were used to enhance beauty and society’s admiration .Ash and certain organic saps might be added to a wound to make the scarring more prominent and or embellished. Climate and custom permitted negligible clothing – which intern promoted body art.

The primitives invented tattooing, scarification and clothing as more permanent adornments. The women as well as the men, in many tribes, submitted to the colouring needle, and bore without flinching even the tattooing of their lips.

In Greenland the mothers tattooed their daughters early, the sooner to get them married off.” Most often, however, tattooing itself was considered insufficiently visible or impressive, and a number of tribes on every continent produced deep scars on their flesh to make them- selves lovelier to their fellows, or more discouraging to their enemies. As Theophile Gautier put it, “having no clothes to embroider, they embroidered their skins.” Flints or mussel shells cut the flesh, and often a ball of earth was placed within the wound to enlarge the scar. The Torres Straits natives wore huge scars like epaulets; the Abcokuta cut themselves to pro- duce scars imitative of lizards, alligators or tortoises. “There is,” says Georg, “no part of the body that has not been perfected, decorated, dis figured, painted, bleached, tattooed, reformed, stretched or squeezed, out of vanity or desire for ornament.”" The Botocudos derived their name from a plug (botoque) which they inserted into the lower lip and the ears in the eighth year of life, and repeatedly replaced with a larger plug until the opening was as much as four inches in diameter. Hottentot women trained the labia mlnora to assume enoromous lengths, so producing at last the “Hottentot apron” so greatly admired by their men. Ear-rings and nose-rings were de rigueur; the natives of Gippsland believed that one who died without a nose-ring would suffer horrible torments in the next life.

It is all very barbarous, says the modern lady, as she bores her ears for rings, paints her lips and her cheeks, tweezes her eyebrows, reforms her eyelashes, powders her face, her neck and her arms, and compresses her feet. The tattooed sailor speaks with superior sympathy of the “savages” he has known; and the Continental student, horrified by primitive mutilations, sports his honorific scars.

Ornaments

From the beginning both sexes preferred ornaments to clothing. Primitive trade seldom deals in necessities; it is usually confined to articles of adornment or play.” Jewelry is one of the most ancient elements of civilization; in tombs twenty thousand years old, shells and teeth have been found strung into necklaces.” From simple beginnings such embellishments soon reached impressive proportions, and played a lofty role in life. The Galla women wore rings to the weight of six pounds, and some Dinka women carried half a hundred weight of decoration. One African belle wore cop- per rings which became hot under the sun, so that she had to employ an attendant to shade or fan her. The Queen of the Wabunias on the Congo wore a brass collar weighing twenty pounds; she had to lie down every now and then to rest. Poor women who were so unfortunate as to have only light jewellery imitated carefully the steps of those who carried great burdens of bedizenment.”

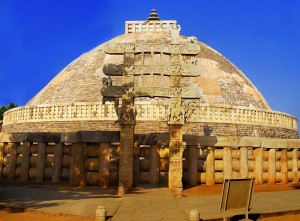

Sculpture

Sculpture is a fine arts discipline that produces artwork in three dimensional forms. Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions and one of the plastic arts. Durable sculptural processes originally used carving (the removal of material) and modelling (the addition of material, as clay), in stone, metal, ceramics, wood and other materials but, since modernism, shifts in sculptural process led to an almost complete freedom of materials and process. A wide variety of materials may be worked by removal such as carving, assembled by welding or modelling.

Sculpture has been central in religious devotion in many cultures, and until recent centuries large sculptures, too expensive for private individuals to create, were usually an expression of religion or politics.Sculpture, like painting, probably owed its origin to pottery: the potter found that he could mold not only articles of use, but imitative figures that might serve as magic amulets, and then as things of beauty in themselves. The Eskimos carved caribou antlers and walrus ivory into figurines of animals and men. Again, primitive man sought to mark his hut, or a totem-pole, or a grave with some image that would indicate the object worshiped, or the person deceased; at first he carved merely a face upon a post, then a head, then the whole post; and through this filial marking of graves sculpture became an art. So the ancient dwellers on Easter Island topped with enormous monolithic statues the vaults of their dead; scores of such statues, many of them twenty feet high, have been found there; some, now prostrate in ruins, were apparently sixty feet tall.

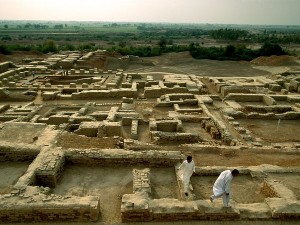

Pottery

For archaeologists, anthropologists and historians the study of pottery can help to provide an insight into past cultures. The study of pottery may also allow inferences to be drawn about a culture’s daily life, religion, social relationships, attitudes towards neighbours, attitudes to their own world and even the way the culture understood the universe.

The first source of art, then, is akin to the display of colors and plumage on the male animal in mating time; it lies in the desire to adorn and beautify the body. And just as self-love and mate-love, overflowing, pour out their surplus of affection upon nature, so the impulse to beautify passes from the personal to the external world. The soul seeks to express its feeling in objective ways, through color and form; art really begins when men undertake to beautify things. Perhaps its first external medium was pottery. The potter’s wheel, like writing and the state, belongs to the historic civilizations; but even without it primitive men or rather women lifted this ancient industry to an art, and achieved merely with clay, water and deft fingers an astonishing symmetry of form; witness the pottery fashioned by the Baronga of South Africa, or by the Pueblo Indians.

When the potter applied colour designs to the surface of the vessel he had formed, he was creating the art of painting. In primitive hands painting is not yet an independent art; it exists as an adjunct to pottery and statuary. Nature men made colours out of clay, and the Andamanese made oil colours by mixing ochre with oils or fats. Such colours were used to ornament weapons, implements, vases, clothing, and buildings. Many hunting tribes of Africa and Oceania painted upon the walls of their caves or upon neighbouring rocks vivid representations of the animals that they sought in the chase.

The Dance

Primitive dance was done mostly for worship. The people worshiped elements of nature or some gods. Another reason why they danced was to keep themselves warm. They didn’t have heated homes, of course and it was pretty cold then as it is now. Another characteristic of primitive dance was that they imitated their daily activities, like fishing or hunting. Their entire life evolved around these activities so of course that would show in the dances they did. The dances were also wild like another person said in here. They had jerky and animal like movements. They also imitated the sounds and movements made by animals and birds. The primitive dance was not done for social interaction and it was performed by men alone. They had a leader who would give the calls. The leader was called a shaman and he was respected by everyone in the tribe.

Even in early days, and probably long before he thought of carving objects or building tombs, man found pleasure in rhythm, and began to develop the crying and warbling, the prancing and preening, of the animal into song and dance. Perhaps, like the animal, he sang before he learned to talk,” and danced as early as he sang. Indeed no art so characterized or expressed primitive man as the dance. He developed it from primordial simplicity to a complexity unrivalled in civilization, and varied it into a thousand forms. The great festivals of the tribes were celebrated chiefly with communal and in-

dividual dancing; great wars were opened with martial steps and chants; the great ceremonies of religion were a mingling of song, drama and dance. What seems to us now to be forms of play were probably serious matters to early men; they danced not merely to express themselves, but to offer suggestions to nature or the gods; for example, the periodic incitation to abundant reproduction was accomplished chiefly through the hypnotism of the dance.

Spencer derived the dance from the ritual of welcoming a victorious chief home from the wars; Freud derived it from the natural expression of sensual desire, and the group technique of erotic stimulation; if one should assert, with similar narrowness, that the dance was born of sacred rites and mummeries, and then merge the three theories into one, there might result as definite a conception of the origin of the dance as can be attained by us today.

Music

Prehistoric music, sometimes called primitive music, covers the first cultural periods of the human species particularly the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras, from its birth to the Ancient Music era that started around 2000-3000 BC, generally considered to coincide with the first appearance of written materials. These eras cover the birth of human cultures comprising chants and instrumental music.

The music probably started with vocal sound experimentation and playing (basic voice playing ie. primitive singing, shouting, crying, murmuring…) that were then structured and used for children’s lullabies, rituals, funerals, celebrations and other kinds of ceremonies. The first wind instruments and percussion instruments appeared during the Paleolithic eras. Some of them were discovered and have been reconstructed. They consist of: bone flutes, ivory flutes, wooden and bamboo flutes; bone whistles like whistling phalanx; bone or wooden rhombus, also named bullroarer, a weighted aerofoil consisting of a rectangular thin slat of bone or wood attached to a cord that is rotated vigorously above self; primitive string instruments like musical bows; primitive percussion instruments like wooden or bone scraper artefacts used with a wooden stick or small bone, seeds, shells, primitive drums with recipients, and other kind of wooden or bone tools hit or knocked over different stones, shells, bones, horns or wood pieces.

From the dance, we may believe, came instrumental music and the drama. The making of such music appears to arise out of a desire to mark and accentuate with sound the rhythm of the dance, and to intensify with shrill or rhythmic notes the excitement necessary to patriotism or procreation. The instruments were limited in range and accomplishment, but almost endless in variety: native ingenuity exhausted itself in fashioning horns, trumpets, gongs, tamtams, clappers, rattles, castanets, flutes and drums from horns, skins, shells, ivory, brass, copper, bamboo and wood; and it ornamented them with elaborate carving and colouring. The taut string of the bow became the origin of a hundred instruments from the primitive lyre to the Stradivarius violin and the modern pianoforte. Professional singers, like professional dancers, arose among the tribes; and vague scales, predominantly minor in tone, were developed.”

With music, song and dance combined, the “savage” created for us the drama and the opera. For the primitive dance was frequently devoted to mimicry; it imitated, most simply, the movements of animals and men, and passed to the mimetic performance of actions and events. So some Australian tribes staged a sexual dance around a pit ornamented with shrubbery to represent the vulva, and, after ecstatic and erotic gestures and prancing, cast their spears symbolically into the pit. The northwestern tribes of the same island played a drama of death and resurrection differing only in simplicity from the medieval mystery and modern Passion plays: the dancers slowly sank to the ground, hid their heads under the boughs they carried, and simulated death; then, at a sign from their leader, they rose abruptly in a wild triumphal chant and dance announcing the resurrection of the soul. In like manner a thousand forms of pantomime described events significant to the history of the tribe, or actions important in the individual life. When rhythm disappeared from these performances the dance passed into the drama, and one of the greatest of art-forms was born.

Art is the creation of beauty; it is the expression of thought or feeling in a form that seems beautiful or sublime, and therefore arouses in us some reverberation of that primordial delight which woman gives to man, or man to woman. The thought may be any capture of life’s significance, the feeling may be any arousal or release of life’s tensions. The form may satisfy us through rhythm, which falls in pleasantly with the alternations of our breath, the pulsation of our blood, and the majestic oscillations of winter and summer, ebb and flow, night and day; or the form may please us through symmetry, which is a static rhythm, standing for strength and recalling to us the ordered proportions of plants and animals, of women and men; or it may please us through colour, which brightens the spirit or intensifies life; or finally the form may please us through veracity because its lucid and transparent imitation of nature or reality catches some mortal loveliness of plant or animal, or some transient meaning of circumstance, and holds it still for our lingering enjoyment or leisurely under- standing. From these many sources come those noble superfluities of life song and dance, music and drama, pottery and painting, sculpture and architecture, literature and philosophy. For what is philosophy but an art one more attempt to give “significant form” to the chaos of experience?

REFERENCE:

BRIFFAULT, ROBERT: The Mothers. 3V. New York, 1927

GEORG, EUGEN: The Adventure of Mankind. New York, 1931

GROSSE, ERNST: Beginnings of Art. New York, 1897.

GROSSE, ERNST: Beginnings of Art. New York, 1897.

LOWIE, R. H.: Primitive Religion. New York, 1924.

LOWIE,R. H.: Are We Civilized? New York, 1929.

LUBBOCK, SIR JOHN: The Origin of Civilization. London, 1912.

MASON, O. T.: Origins of Invention. New York, 1899.

MASON, W. A.: History of the Art of Writing. New York, 1920.

MULLER-LYER,F.: Evolution of Modern Marriage. New York, 1930.

MULLER-LYER,F.: History of Social Development. New York, 1921.

MULLKR-LYER,F.: The Family. New York, 1931.

PI JOAN, JOS.: History of Art. 3V. New York, 1927

PRATT, W. S.: The History of Music. New York, 1927.

RATZEL, F.: History of Mankind. 2v. London, 1896.

RENARD, G.: Life and Work in Prehistoric Times. New York, 1929.

SPENCER, HERBERT: Principles of Sociology. 3V. New York, 1910.

SUMNER, W. G. and KELLER, A. G.: Science of Society. 3V. New Haven, 1928.

SUMNER, W. G.: Folkways. Boston, 1906.