Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Se. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Jean Piaget explains his’ Theory of Intellectual Development ‘on the basis of certain basic concepts. These are generally known as:

Jean Piaget explains his’ Theory of Intellectual Development ‘on the basis of certain basic concepts. These are generally known as:

- Concept of Schemes

- Concept of Assimilation

- Concept of Accommodation

Concept of Schemes , holds that, to know an object one must act upon it, either physically or mentally. These physical or mental actions can displace objects or connect, combine, take apart and reassemble them. The activities that people perform on objets are known as SCHEMES. Schemes are not particular actions or responses; they what can be repeated and generalized in particular acts.

Concept of Assimilation, holds that the child needs the environment in order to develop his intelligence. Intellectual assimilation is similar to biological assimilation. Piaget wrote: From a biological point of view, assimilation is the integration of external elements into evolving or completed structures of an organism. In its usual connection, the assimilation of food consists of a chemical transformation that incorporates it into organism.

The evolving or completed structures are the schemes. Assimilation is the process of extracting from the environment what is needed for developing and maintaining schemes. If the schemes are stable or completed, assimilation operates as a simple digestive process in which the organs of digestion undergo relatively little change. Assimilation is not exclusively dependent upon what is available in the environment. It also depends upon the schemes already available even in the process of changing them The child’s response to the environment, therefore, is not unlimited-that is, it is not controlled only by the environment.

Thus assimilation accounts for the child’s ability to act on and understand something new in terms of already familiar( his available schemes ). If the child were limited to assimilation, he would not develop new schemes- new capacities for assimilating new objects and events.

Concept of Accommodation, Piaget considers accommodation as any change of a scheme by the elements it assimilates. The progressive modification of schemes through accommodation allows the child to develop his capabilities beyond the point of dealing with the immediate physical environment. The child can reach a stage where he can solve problems through mental calculation alone.

Concept of Equilibration-Piaget holds equilibration as the process that produces progressive equilibrium between assimilation and accommodation. It is the process of seeking mental balance. Equilibration functions as a thermostat that maintains a balance between cold and hot. In the body it functions to keep a balance between such states as activity and rest. Equibration is a dynamic, not a static function. It is a process of decent ration whereby the child moves from stages in which he is centered on his own actions and viewpoints to stages in which he can take the point of view of objects and other people. It moves development from simple to more complex schemes through the dual action of assimilation and accommodation.

Periods of Intellectual Development

The stage-by-stage nature of Piaget’s theory, with each stage linked to an age group for whom the stage is typical, strongly suggests to many people that at a particular age, children are supposed to be functioning at a particular stage. It’s important to keep in mind that Piaget’s theory is intended to talk about how an average child might be functioning at a particular age; it is not a pronouncement about how any particular individual child should be functioning. Children develop uniquely and at their own pace depending upon their temperament (the inherited component of their personalities), genetic makeup, supports available to them in their environments, and their learning experiences. Different children will show mastery of specific operations sooner than will others, or display them in some situations but not in others. Newer research also shows that context affects children’s abilities as well. Most children will display more advanced operations when in familiar or mandatory environments .They may tend to become confused and perform more poorly when confronted with novel situations.

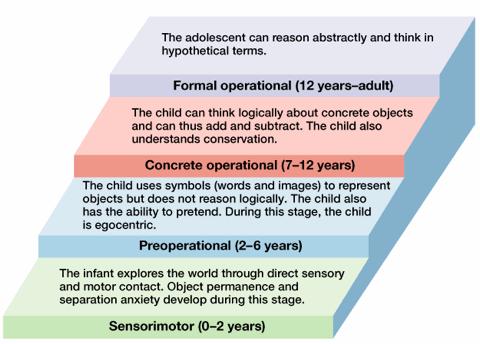

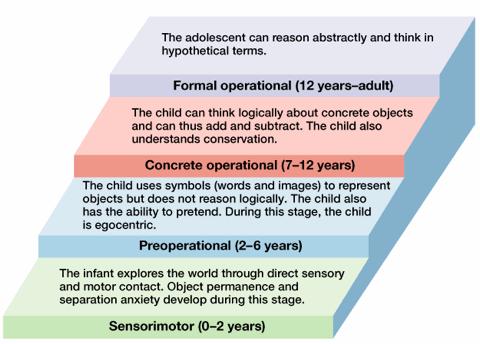

Piaget divides the intellectual development into four periods:

A- Sensorimotor Period

B- Preoperational Period

C- Concrete Operational Period

D- Formal operations Period

Sensorimotor Period

Sensorimotor Period

The Sensorimotor Stage is the first stage Piaget uses to define cognitive development. The first period of sensorimotor period of intellectual development is the sensorimotor period that lasts to about one and a half years of age. In the first half of this period the child’s activity is centered on his own body. In the second half, the child develops schemes of practical intelligence that enable him to deal with objects in space.

The Sensorimotor Stage is the first stage Piaget uses to define cognitive development. The first period of sensorimotor period of intellectual development is the sensorimotor period that lasts to about one and a half years of age. In the first half of this period the child’s activity is centered on his own body. In the second half, the child develops schemes of practical intelligence that enable him to deal with objects in space.

During this period, infants are busy discovering relationships between their bodies and the environment. Researchers have discovered that infants have relatively well developed sensory abilities. The child relies on seeing, touching, sucking, feeling, and using their senses to learn things about themselves and the environment. Piaget calls this the sensorimotor stage because the early manifestations of intelligence appear from sensory perceptions and motor activities.

During the early stages, infants are only aware of what is immediately in front of them. They focus on what they see, what they are doing, and physical interactions with their immediate environment.

Because they don’t yet know how things react, they’re constantly experimenting with activities such as shaking or throwing things, putting things in their mouths, and learning about the world through trial and error. The later stages include goal-oriented behavior which brings about a desired result.

At about age 7 to 9 months, infants begin to realize that an object exists even if it can no longer be seen. This important milestone — known as object permanence — is a sign that memory is developing.

After infants start crawling, standing, and walking, their increased physical mobility leads to increased cognitive development. Near the end of the sensorimotor stage, infants reach another important milestone — early language development, a sign that they are developing some symbolic abilities.

During the Sensory Motor Stage, knowledge about objects and the ways that they can be manipulated is acquired. Through the acquisition of information about self and the world, and the people in it, the baby begins to understand how one thing can cause or affect another, and begins to develop simple ideas about time and space. Infants realize that an object can be moved by a hand (concept of causality), and develop notions of displacement and events. An important discovery during the latter part of the sensorimotor stage is the concept of “object permanence”.

Object permanence is the awareness that an object continues to exist even when it is not in view. In young infants, when a toy is covered by a piece of paper, the infant immediately stops and appears to lose interest in the toy (see figure above). This child has not yet mastered the concept of object permanence. In older infants, when a toy is covered the child will actively search for the object, realizing that the object continues to exist.

After a child has mastered the concept of object permanence, the emergence of directed groping“ begins to take place. With directed groping, the child begins to perform motor experiments in order to see what will happen. During directed groping, a child will vary his movements to observe how the results will differ. The child learns to use new means to achieve an end. The child discovers he can pull objects toward himself with the aid of a stick or string, or tilt objects to get them through the bars of his playpen. The child begins to recognize cause-and-effect relationships at this stage, allowing the development of intentionally. Once a child knows what the effects of his activities will be, he can intend these effects.

Mary Ann Spencer described the six stages of sensorimotor development periods as;

Stage 1- (0-1 month ) characterized by neonatal reflexes and gross, uncoordinated body movements. Stage of complete egocentricism with no distinction between self and outer reality; no awareness of self as such.

Stage 2- ( 1-4 months) New response pattern are formed by chance from combination of primitive reflexes. The infant’s fist accidently finds its way into his mouth through a coordination of arm moving and sucking.

Stage 3-(4-8 months) New response patterns are coordinated and repeated intentionally in order to maintain interesting changes in the environment.

Stage4- (8-12 months) More complex coordination of previous behavior patterns, both motor and perceptual. Baby pushes aside obstacles or uses parent’s hand as a means to a desired end.Emergence of anticipatory and intentional behavior; beginning of search for vanished articles.

Stage 5 (12-18 months) Familiar behavior patterns varied in different ways as if to observe different results. Emergence of directed grouping toward a goal, and of new means-end manipulations for reaching desired objects.

Stage6-(11/2 to 2 years ) Internalization of sensorimotor behavior patterns and beginning of symbolic representation. Invention of new means through internal experimentation rather than external trial and error.

To illustrate threes stages, consider the infant’s reactions to the presence and disappearance of objects.

In the 1st stage the infant is passive to the world of objects. The newborn infant will close his hand on anything that lightly touches it. He grasps passively, but he does not search actively for any objects. In a random effort to assimilate the object environment the new born makes impulsive movements of his limbs, but there is no attempt to direct these movements towards the grasping of particular objects. This passive release by stimulation gives way to active grouping, as we see in the infants sucking behavior. Very early in the infant’s life he learns to group with his mouth for the nipple of the breast. He assimilates the nipple to innate sucking scheme.

At the 2nd stage the world of objects is still only an extension of the infants needs and movements. As an object the nipple has no permanence or constancy. When it disappears, he made no active effort to find it. Out of sight ,out of mind. By the 2nd stage however, the infant knows when he is in the vicinity of the nipple. He is sensitive to the smooth breast skin surrounding the nipple. He is, therefore, more actively engaged in the nipple search than when he merely awaited its insertion.

At the 3rd stage there is still more progress from passive responding to active search. The infant’s behavior becomes intentional-centered or producing some result in the environment. In this stage the child begins to develop primitive notions of space, causality and time and shows the beginning of imitation. The child in short, begins to construct a basic reality.

At the 4th stage the infant’s behavior becomes even more intentional and active. This is illustrated most graphically in the child’s search for vanished objects.. The infant no longer behaves as if an object ceases to exist when it disappears from sight.

At the 5th stage there is more active experimentation by the infant. The child discovers new means for attaining various goals. When the infant does not witness an event, it lacks reality for him. Aside from attaining a somewhat better scheme for object performance, in this stage the child develops a greater interest in novelty and in the imitation of new models and gains better understanding of space time and cause effect relationships.

In the 6th stage the infant develops schemes that allow him to represent mentally objects and events. He can imagine actions as well as execute them.

The process of making new schemes out of old schemes involve both assimilation and accommodation. When the infant’s old schemes of objects as simple extensions of his motion proves to be inadequate for his growing physical potential, assimilation of new aspects of the environment results in the accommodation of the old scheme and the development of new ones. The new schemes are more inclusive and absorb the old schemes in a kind of intellectual hierarchy. This way the infant’s schemes for sucking and object permanence contain all of the schemes of earlier stage but become subordinate to the new, more general schemes that enable the child to manipulate his environment more fully.

In short the sensorimotor period begins with the infant entering its attention on its own body, a period lasting from 7 to 9 months. It is followed by a period of approximately equal length in which the child becomes aware of the independent of objects and space outside his own body.

Preoperational Period

This second period begins around 11/2 to 2 years of age and extend to the age of 7 or 8 years. During this stage, children’s thought processes are developing, although they are still considered to be far from ‘logical thought’, in the adult sense of the word. The vocabulary of a child is also expanded and developed during this stage, as they change from babies and toddlers into ‘little people’.

Piaget calls this period of representational intelligence because the child is able to represent reality as language and mental imagery. For the child, it is the period of magic during which words, pictures, emotions, fantasies and dreams all seem part of an external reality. The child is not decentered in this thinking. He sees everything from a single point of view, his own. During this period assimilation appears to overweigh accommodation. There is pleasure in activities themselves; real objects become symbolic( using wooden cubical blocks to build a tower) ; and in rule games symbols are defined by social convention.

This period can be devided into two stages. Pulaski described these stages as follos:

A- Preconceptual Stage (2 to 4 years) Development of perceptual constancy and representation through drawing, dreams, and symbolic play. Beginning of first overgeneralized attempts at conceptualization, in which representative of a class are not distinguished from the class itself ( e.g., all dogs are called by the name of the child,s own dog).

B- – Perceptual or Intuitive Stage (4 to 7 years). Prelogical reasoning appears. Based on perceptual appearances untempered by reversibility (e.g., Grand father wearind a new type of dress is not recognized as Grandfather). Ttial and error may lead to an intuitive discovering of correct relationships, but the child is unable to take more than one attribute into account at one time.

Characteristics of Preoperational Period

A.The preoperational stage, Piaget’s second stage, is marked by rapid growth in representational, or symbolic, mental activity.

B.Advances in Mental Representation . Language is our most flexible means of mental representation. . Piaget believed that sensorimotor activity provides the foundation for language, just as it under lies deferred imitation and make-believe play.

C. Make-Believe Play . Make-believe play increases dramatically during early childhood. Piaget believed that through pretending, young children practice and strengthen newly acquired representational schemes. . Development of Make-Believe Play. a. Over time, play becomes increasingly detached from the real-life conditions associated with it. b. Make-believe play gradually becomes less selfcentered as children realize that agents and recipients of pretend actions can be independent of themselves. c. Play also includes increasingly more complex scheme combinations. .

Sociodramatic play is the make-believe play with peers that first appears around age 2 1/2 and increases rapidly until 4 to 5 years. e. The emergence of sociodramatic play signals an awareness that make-believe play is a representational activity.

Advantages of Make-Believe. . Today, Piaget’s view of make-believe- as mere practice of representational schemes is regarded as too limited. b. In comparison to social nonpretend activities, during social pretend preschoolers’ interactions last longer, show more involvement, draw larger numbers of children into the activity, and are more cooperative. Preschoolers who spend more time at sociodramatic play are advanced in general intellectual development and seen as more socially competent by their teachers. d. In the past, creating imaginary companions, invisible characters with whom children form a special relationship, was viewed as a sign of maladjustment. Yet recent research demonstrates that children who have them display more complex pretend play, are advanced in mental representation, and are more sociable with peers.

D. Spatial Representation .Spatial understanding improves rapidly over the third year of life. With this representational capacity, children realize that a spatial symbol stands for a specific state of affairs in the real world. Insight into one type of symbol-real world relation, such as that represented by a photograph, helps preschoolers understand others, such as simple maps. Providing children with many opportunities to learn about the functions of diverse symbols, such as picture books, models, maps, and drawings, enhances spatial representation.

E. Limitations of Preoperational Thought . Piaget described preschool children in terms of what they cannot, rather than can, understand. Operations are mental representations of actions that obey logical rules. In the preoperational stage, children’s thinking is rigid, limited to one aspect of a situation at a time, and strongly influenced by the way things appear at the moment. Egocentric and Animistic Thinking. a. Egocentrism is the inability to distinguish the symbolic viewpoints of others from one’s own.

Important Features of Pre-operational stage

Pre-operational children are usually ‘ego centric’, meaning that they are only able to consider things from their own point of view, and imagine that everyone shares this view, because it is the only one possible. Egocentrism refers to the child’s inability to see a situation from another person’s point of view. According to Piaget, the egocentric child assumes that other people see, hear and feel exactly the same as the child does. Piaget wanted to find out at what age children decenter – i.e. become no longer egocentric.

In psychology, egocentrism is defined as a) the incomplete differentiation of the self and the world, including other people and b) the tendency to perceive, understand and interpret the world in terms of the self. The term derives from the Greek egô, meaning “I.” An egocentric person has no theory of mind, cannot “put himself in other people’s shoes,” and believes everyone sees what he sees (or that what he sees in some way exceeds what others see.)

It appears that this is shown mostly in younger children. They are unable to separate their own beliefs,thoughts and ideas from others. For example, if a child sees that there is candy in a box, he assumes that someone else walking into the room also knows that there is candy in that box. He reasons that “since I know it, you should too”. As stated previously this may be rooted in the limitations in the child’s theory of mind skills. However, it does not mean that children are unable to put their selves in someone else’s shoes. As far as feelings are concerned, it is shown that children exhibit empathy early on and are able to cooperate with others and be aware of their needs and wants.

Jean Piaget claimed that young children are egocentric. This does not mean that they are selfish, but that they do not have the mental ability to understand that other people may have different opinions and beliefs from themselves. Piaget did a test to investigate egocentrism called the mountains study. He put children in front of a simple plaster mountain range and then asked them to pick from four pictures the view that he, Piaget, would see. Younger children picked the picture of the view they themselves saw.

Gradually during this stage, a certain amount of ‘decentering’ occurs. This is when someone stops believing that they are the centre of the world, and they are more able to imagine that something or someone else could be the centre of attention.

According to Piaget, egocentrism of the young child leads them to believe that everyone thinks as they do, and that the whole world shares their feelings and desires. This sense of oneness with the world leads to the child’s assumptions of magic omnipotence. Not only is the world created for them, they can control it. This leads to the child believing that nature is alive, and controllable. This is a concept of egocentrism known as”animism”, the most characteristic of egocentric thought.

‘Animism’ is also a characteristic of the Pre-operational stage. This is when a person has the belief that everything that exists has some kind of consciousness. Another key feature which children display during this stage is animism. Animism is the belief that inanimate objects (such as toys and teddy bears) have human feelings and intentions.

. A reason for this characteristic of the stage, is that the Pre-operational child often assumes that everyone and everything is like them. Therefore since the child can feel pain, and has emotions, so must everything else.

Closely related to animism is artificialism, or the idea that natural phenomena are created by human beings. Such as the sun is created by a man with a match. “Realism” is the child’s notion that their own perspective is objective and absolute. The child thinks from one perspective and regards this reality as absolute. Names, for example, are real to the child. The child can’t realize that names are only verbal labels, or conceive the idea that they could have been given a different name.

During the pre-operational period, the child begins to develop the use of symbols (but can not manipulate them), and the child is able to use language and words to represent things not visible. Also, the pre-operational child begins to master conservation problems.

By the age of four children are developing a more complete understanding of concepts and tend to have stopped reasoning tranductively (Lefrancois, 1995). However their thought is dominated more by perception than logic. This is clearly illustrated by conservation experiments. In such an experiment a pre-operational child may be shown two balls of clay, that the child acknowledges are equal in size, one of which is then squashed. The child is now asked if both lots of clay are equal. A child at this stage will say they are no longer equal.

Although the child is still unable to think in a truly logical fashion, they may begin to treat objects as part of a group. The pre-operational child may have difficulty with classification. This is because, to a pre-operational child, the division of a parent class into subclasses destroys the parent group (Lefrancois, 1995). For example, a child has a pile of toy vehicles which are then split into trucks and cars. Next the child is asked ‘Tell me, are there more trucks than vehicles, or less, or the same number?’ the child will almost always say there are more trucks than vehicles!

Another aspect of the Pre-operational stage in a child, is that of ‘symbolism’. This is when something is allowed to stand for or symbolise something else. ‘Moral realism’ is a fourth aspect of this stage, this is the belief that the child’s way of thinking about the difference between right and wrong, is shared by everyone else around them. One aspect of a situation, at one time, is all that they are able to focus on, and it is beyond them to consider that anything else could be possible. Due to this aspect of the stage, children begin to respect and insist on obedience of rules at all times, and they are not able to take anything such as motives into account.

During this stage, young children are able to think about things symbolically. Their language use becomes more mature. They also develop memory and imagination, which allows them to understand the difference between past and future, and engage in make-believe.

But their thinking is based on intuition and still not completely logical. They cannot yet grasp more complex concepts such as cause and effect, time, and comparison.

Concrete Operations Stage

The Concrete Operations Stage, was Piaget’s third stage of cognitive development in children. The concrete operational stage includes those who are approximately in-between ages 7 to 11 years old.

At this time, elementary-age and preadolescent children demonstrate logical, concrete reasoning. Children’s thinking becomes less egocentric and they are increasingly aware of external events. They begin to realize that one’s own thoughts and feelings are unique and may not be shared by others or may not even be part of reality. Children also develop operational thinking — the ability to perform reversible mental actions.

During this stage, however, most children still can’t tackle a problem with several variables in a systematic way. During this stage children are able to reason logically as long as the reasoning can be applied to concrete and specific examples. In this stage they are also able to observe and understand the idea of conservation. During this stage, children begin to reason logically, and organize thoughts coherently. However, they can only think about actual physical objects, and cannot handle abstract reasoning. They have difficulty understanding abstract or hypothetical concepts.

For example, if a specific amount of water is poured into a tall, skinny glass and then poured into a short, wide glass, concrete operational thinkers are able to understand that the volume of the water did not change. Overall, logical reasoning is present in this stage, but cannot be utilized unless applied to concrete examples

During this stage, the thought process becomes more rational, mature and ‘adult like’, or more ‘operational’, Although this process most often continues well into the teenage years. The process is divided by Piaget into two stages, the Concrete Operations, and the Formal Operations stage, which is normally undergone by adolescents.

In the Concrete Operational stage, the child has the ability to develop logical thought about an object, if they are able to manipulate it. By comparison, however, in the Formal Operations stage, the thoughts are able to be manipulated and the presence of the object is not necessary for the thought to take place.

A mental operation, in the Piagetian way of thinking, is the ability to accurately imagine the consequences of something happening without it actually needing to happen. During a mental operation, children imagine “what if” scenarios which involve the imaginal transformation of mental representations of things they have experienced in the world; people, places and things. The ability to perform mental arithmetic is a good example of an operation. These sorts of operations are “concrete” because they are based on actual people, places and things that children have observed in the environment. Children’s mental representations remain concretely linked to things they have seen and touched throughout the middle childhood period. Because their representations are limited to the tangible, touchable and concrete, their appreciation of the consequences of events is similarly limited, local and concrete in scope. At this age, children can easily tell you that if the fence breaks open, that the dog will be able to get out. However, they cannot easily think about more abstract things like what it will really mean for the family if a parent loses her job. In the Piagetian theory, it is not until children enter adolescence that they become capable of more abstract “formal” operations involving representations of things that are intangible and abstract (without any tight link back to a tangible person, place or thing), such as “liberty”, “freedom” or “divinity”.

Belief in animism and ego centric thought tends to decline during the Concrete Operational stage, although, remnants of this way of thinking are often found in adults

Piaget described multiple operations that children begin to master in middle childhood, including conservation, decent ration, reversibility, hierarchical classification, seriation, and spatial reasoning. These are technical terms, all of which will be described below in greater detail. Obviously, children do not learn the names of these various operations or proudly point out to their parents that they’ve mastered these skills. Children just start doing these things without having realized what they’ve accomplished. However, these new skills are often noticeable by outside observers familiar with children’s progress. In their own subtle way, children’s mastery of these operations is a tremendous accomplishment, easily as impressive a feat as any physical accomplishment children might learn.

This stage is also characterized by a loss of egocentric thinking. During this stage, the child has the ability to master most types of conservation experiments, and begins to understand reversibility. Conservation is the realization that quantity or amount does not change when nothing has been added or taken away from an object or a collection of objects, despite changes in form or spatial arrangement. The concrete operational stage is also characterized by the child’s ability to coordinate two dimensions of an object simultaneously, arrange structures in sequence, and transpose differences between items in a series. The child is capable of concrete problem-solving. Categorical labels such as “number” or “animal” are now available to the child.

Let’s now explore the various concrete operations children start to master during this middle childhood stage of their development:

Conservation

Conservation involves the ability to understand when the amount of something remains constant across two or more situations despite the appearance of that thing changing across those situations. The idea of conservation can be applied to any form of measurement, including number, mass, length, area, volume, etc. Piaget’s famous example of conservation was performed using liquids poured into different shaped containers. Though the volume of liquid remains constant across the two containers, each container has a very different visual appearance, with one being tall and thin, while another was short and wide. Using this setup, Piaget was able to show that middle childhood-aged children were able to appreciate that the total amount of liquid was unchanged despite being poured into differently shaped containers. Younger children were characteristically fooled by the appearance of the containers and tended to conclude that wider, shorter containers held less water than taller, thinner containers.

Logic:

Piaget determined that children in the concrete operational stage were fairly good at the use of inductive logic. Inductive logic involves going from a specific experience to a general principle. On the other hand, children at this age have difficulty using deductive logic, which involves using a general principle to determine the outcome of a specific event.

Reversibility:

A second new ability gained in the concrete operational stage is reversibility. This refers to the ability to mentally trace backwards, and is of enormous help to the child in both their problem solving and the knowledge they have of their own problem solving. For the former this is because they can see that in a conservation task, for example, the change made could be reversed to regain the original properties. With respect to knowledge of their own problem solving, they become able to retrace their mental steps, allowing an entirely new level of reflection.

Once children have learnt to conserve, they learn about ‘reversibility’. This means that they learn that if things are changed, they will still be the same as they used to be. For example, they learn that if they spread out the pile of blocks, there are still as many there as before, even though it looks different!

One of the most important developments in this stage is an understanding of reversibility, or awareness that actions can be reversed. An example of this is being able to reverse the order of relationships between mental categories. For example, a child might be able to recognize that his or her dog is a Labrador, that a Labrador is a dog, and that a dog is an animal.

A large portion of the defining characteristics of the stage can be understood in terms of the child overcoming the limits of stage two, known as the pre-operational stage. The pre-operational child has a number of cognitive barriers which are subsequently broken down, and it is important to note that overcoming these obstacles is not due to gradual improvement in abilities the child already possesses. Rather the changes are genuine qualitative shifts, corresponding to new abilities being acquired.

Perceptual domination

A second limitation which is overcome in the concrete operational stage is the perceptual domination of one aspect of a situation. Before the stage begins, the child’s perception of any situation or problem will be dominated by one aspect; this is best illustrated by the failure of pre-operational children to pass Piaget’s conservation tasks

These shifts in the child’s thinking lead to a number of new abilities which are also major, positively defined characteristics of the concrete operational stage. The most frequently cited ability is conservation. Now that children are no longer perceptually dominated by one aspect of a situation, they can track changes much more easily and recognize that some properties of an object will persevere through change. Conservation is always gained in the same order, firstly with respect to number, followed secondly by weight, and thirdly by volume.

Concrete operational children also gain the ability to structure objects hierarchically, known as classification. This includes the notion of class inclusion, e.g. understanding an object being part of a subset included within a parent set, and is shown on Piaget’s inclusion task, asking children to identify, out of a number of brown and white wooden beads, whether there were more brown beads or wooden beads

seriation

seriation is another new ability gained during this stage, and refers to the child’s ability to order objects with respect to a common property. A simple example of this would be placing a number of sticks in order of height. An important new ability which develops from the interplay of both seriation and classification is that of numeration. Whilst pre-operational children are obviously capable of counting, it is only during the concrete operational stage that they become able to apply mathematical operators, thanks to their abilities to order things in terms of number (seriation) and to split numbers into sets and subsets (classification), enabling more complex multiplication, division and so on.

Finally, and also following the development of seriation, is transitive inference. This is the name given to children’s ability to compare two objects via an intermediate object. So for instance, one stick could be deemed to be longer than another by both being individually compared to another (third) stick.

Flavell summarized three limitation of the period of concrete operations:

(1) The operations are oriented toward concrete things and events in the immediate present, so movement toward the nonpresent, or potential, is limited. The child during this period acts as if his primary task were to organize and order what is immediately present; the real does not become a special case of the possible.

(2) The child has to relinquish the various physical attributes (such as mass, weight, volume) of objects and events one by one. If, for example, he understands that there is as much clay in object A as in object B (mass0, despite the difference in shape, the child will still need considerable time to understand that the weight and the volume of the clay also remain the same.

(3) Each of the groupings which the child develops in this period remains an isolated organization and does not form and integrated system of thought. All three of these limitations are removed in the period of formal operations.

Formal Operation period

The formal operational stage is the fourth and final stage of cognitive development in Piaget’s theory. This stage, which follows the Concrete Operational stage, commences at around 11 or 12 years of age (puberty) and continues into adulthood. In this stage, individuals move beyond concrete experiences and begin to think abstractly, reason logically, and draw conclusions from the information available as well as apply all these processes to hypothetical situations.

During the period from 11 to 15, the adolescent acquires the adult capacity for abstract thought. In the previous period the child is only beginning to extend his thought from the actual to the potential. Adolescents who reach this fourth stage of intellectual development are able to logically use symbols related to abstract concepts, such as algebra and science. They can think about multiple variables in systematic ways, formulate hypotheses, and consider possibilities. They also can ponder abstract relationships and concepts such as justice.

Although Piaget believed in lifelong intellectual development, he insisted that the formal operational stage is the final stage of cognitive development, and that continued intellectual development in adults depends on the accumulation of knowledge

Characteristics of Formal Operation Period

These characteristics explain ‘ adolescent’s taste for theorizing and criticizing.’

A-Possible versus the real-

No longer exclusively preoccupied with the sober business of trying to stabilize and organize just what comes directly to the senses, the adolescent has, through this new orientation, the potentiality og imagining all that might be there- both the very obvious and the very subtle- and thereby of much better insuring the finding of all that is there. The adolescent, therefore, theorizes about and criticizes the present operation of the world because he conceives of many possible ways in which it could operate and many alternative ways in which it could be better.

B-The Hypothetical-deductive-

To discover the real among the possible requires that the possible be cast as hypotheses, which may be confirmed or rejected. They use hypothetical-deductive reasoning, which means that they develop hypotheses or best guesses and systematically deduce, or conclude, which is the best path to follow in solving the problem. However, Suppes (1982) found that deductive reasoning can be present before Piaget suggests formal operations begin When faced with a problem, adolescents come up with a general theory of all possible factors that might affect the outcome and deduce from it specific hypotheses that might occur. They then systematically treat these hypotheses to see which ones do in fact occur in the real world. Thus, adolescent problem solving begins with possibility and proceeds to reality.

C- Propositional thinking-

The adolescent does not consider only raw data but also sentences which contain these data, he takes the results, and puts them in sentence form ,and begins to find relationships among the sentences. . Adolescents can focus on verbal assertions and evaluate their logical validity without making reference to real-world circumstances. In contrast, concrete operational children can evaluate the logic of statements by considering them against concrete evidence only.

D- Ability to reason contrary to fact

Another characteristic of the individual is their ability to reason contrary to fact. That is, if they are given a statement and asked to use it as the basis of an argument they are capable of accomplishing the task. For example, they can deal with the statement “what would happen if snow were black

In the period of formal operation the adolescent engages in his first scientific reasoning. He is capable of planning truly scientific investigations and he can vary the factors in all possible combinations and in an orderly fashion. infect, he appears to be capable of discovering the basic laws of physics with the help of simple apparatuses.. Unlike the younger child, who lives in the world of the possible and the hypothetical- the world of future. Since he is capable of reflective thought, he can consider his future and the future of the society in which he lives. He develops a special ego-centricism, in which he combines an extravagant belief in thought with sweeping disregard for the practicality of the designs and the reforms he proposes.

Those who are in this stage are roughly 11 to 15 years old and are advancing from logical reasoning with concrete examples to abstract examples. The need for concrete examples is no longer necessary because abstract thinking can be used instead. In this stage adolescents are also able to view themselves in the future and can picture the ideal life they would like to pursue. Some theorists believe the formal operational stage can be divided into two sub-categories: early formal operational and late formal operation thought. Early formal operational thoughts may be just fantasies, but as adolescents advance to late formal operational thought the life experiences they have encountered changes those fantasy thoughts to realistic thoughts.

This brief description concludes our consideration of the periods of intellectual development as identified by Piaget’s and his associates.