Dr. V.K. Maheshwari, Former Principal

K.L.D.A.V(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Behaviourism is based on the assumption that learning occurs through interactions with the environment. Two other assumptions of this theory are that the environment shapes behavior and that taking internal mental states such as thoughts, feelings and emotions into consideration is useless in explaining behaviour.

The most basic form is associative learning, i.e., making a new association between events in the environment. There are two forms of associative learning: classical conditioning and operant conditioning. One of the best-known aspects of behavioural learning theory is classical conditioning. , Classical conditioning is a learning process that occurs through associations between an environmental stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus. In classical conditioning, the conditioned response is the learned response to the previously neutral stimulus.

Conditioning, is a behavioural process whereby a response becomes more frequent or more predictable in a given environment as a result of reinforcement, with reinforcement typically being a stimulus or reward for a desired response. Early in the 20th century, through the study of reflexes, physiologists in Russia, England, and the United States developed the procedures, observations, and definitions of conditioning. After the 1920s, psychologists turned their research to the nature and prerequisites of conditioning.

Stimulus-response (S-R) theories are central to the principles of conditioning. They are based on the assumption that human behaviour is learned. One of the early contributors to the field, American psychologist Edward L. Thorndike, postulated the Law of Effect, which stated that those behavioral responses (R) that were most closely followed by a satisfactory result were most likely to become established patterns and to reoccur in response to the same stimulus (S). This basic S-R scheme is referred to as unmediated. When an individual organism (O) affects the stimuli in any way—for example, by thinking about a response—the response is considered mediated. The S-O-R theories of behaviour are often drawn to explain social interaction between individuals or groups.

Definition of Classical conditioning:

Learning in which a stimulus initially incapable of evoking a certain response becomes able to do so by repeated pairing with another stimulus that does evoke the response.

A learning process in which an organism’s behaviour becomes dependent on the occurrence of a stimulus in its environment

A process in which a stimulus that was previously neutral, as the sound of a bell, comes to evoke a particular response, as salivation, by being repeatedly paired with another stimulus that normally evokes the response, as the taste of food

A process of changing behaviour by rewarding or punishing a subject each time an action is performed.

Process of behaviour modification by which a subject comes to associate a desired behaviour with a previously unrelated stimulus.

A process of behaviour modification by which a subject comes to respond in a desired manner to a previously neutral stimulus that has been repeatedly presented along with an unconditioned stimulus that elicits the desired response.

Basic Principles

In order to understand how more about how classical conditioning works, it is important to be familiar with the basic principles of the process.

The Unconditioned Stimulus

The unconditioned stimulus is one that unconditionally, naturally, and automatically triggers a response. In this example, the smell of the food is the unconditioned stimulus. An unconditioned stimulus (UCS) such as food, generates and instinctual reflexive, unlearned behaviour, such as salivation when eating.

The Unconditioned Response

The unconditioned response is the unlearned response that occurs naturally in response to the unconditioned stimulus. The salivation was called an unconditioned response (UCR) because it was not learned In our example, the feeling of hunger in response to the smell of food is the unconditioned response.

The Conditioned Stimulus

The conditioned stimulus is previously neutral stimulus that, after becoming associated with the unconditioned stimulus, eventually comes to trigger a conditioned response. In our earlier example, suppose that when you smelled your favorite food, you also heard the sound of a whistle. While the whistle is unrelated to the smell of the food, if the sound of the whistle was paired multiple times with the smell, the sound would eventually trigger the conditioned response. In this case, the sound of the whistle is the conditioned stimulus The bell, formerly a neutral sound to the dog, become a conditioned learned stimulus (CLS).

The Conditioned Response

The conditioned response is the learned response to the previously neutral stimulus. In our example, the conditioned response would be feeling hungry when you heard the sound of the whistle. and the salivation a conditioned response (CR).

Fundamental Experiment-

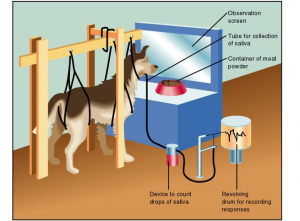

The concept of classical conditioning is studied by every entry-level psychology student, so it may be surprising to learn that the man who first noted this phenomenon was not a psychology at all. Ivan Pavlov was a noted Russian physiologist who went on to win the 1904 Nobel Prize for his work studying digestive processes. It was while studying digestion in dogs that Pavlov noted an interesting occurrence – his canine subjects would begin to salivate whenever an assistant entered the room.

In his digestive research, Pavlov and his assistants would introduce a variety of edible and non-edible items and measure the saliva production that the items produced. Salivation, he noted, is a reflexive process. It occurs automatically in response to a specific stimulus and is not under conscious control. However, Pavlov noted that the dogs would often begin salivating in the absence of food and smell. He quickly realized that this salivary response was not due to an automatic, physiological process.

. While studying the role of saliva in dogs’ digestive processes, Pavlov stumbled upon a phenomenon he labeled “psychic reflexes.” While an accidental discovery, he had the foresight to see the importance of it. Pavlov’s dogs, restrained in an experimental chamber, were presented with meat powder and they had their saliva collected via a surgically implanted tube in their saliva glands. Over time, he noticed that his dogs who begin salivation before the meat powder was even presented, whether it was by the presence of the handler or merely by a clicking noise produced by the device that distributed the meat powder.

Fascinated by this finding, Pavlov paired the meat powder with various stimuli such as the ringing of a bell. After the meat powder and bell (auditory stimulus) were presented together several times, the bell was used alone. Pavlov’s dogs, as predicted, responded by salivating to the sound of the bell (without the food). The bell began as a neutral stimulus (i.e. the bell itself did not produce the dogs’ salivation). However, by pairing the bell with the stimulus that did produce the salivation response, the bell was able to acquire the ability to trigger the salivation response. Pavlov therefore demonstrated how stimulus-response bonds (which some consider as the basic building blocks of learning) are formed. He dedicated much of the rest of his career further exploring this finding.

In technical terms, the meat powder is considered an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and the dog’s salivation is the unconditioned response (UCR). The bell is a neutral stimulus until the dog learns to associate the bell with food. Then the bell becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS) which produces the conditioned response (CR) of salivation after repeated pairings between the bell and food.

Process of Classical Conditioning

Conditioning is a form of learning in which either (1) a given stimulus (or signal) becomes increasingly effective in evoking a response or (2) a response occurs with increasing regularity in a well-specified and stable environment. The type of reinforcement used will determine the outcome. When two stimuli are presented in an appropriate time and intensity relationship, one of them will eventually induce a response resembling that of the other. The process can be described as one of stimulus substitution. This procedure is called classical (or respondent) conditioning.

Process of conditioning

The entire process of conditioning can be explained like this:

Food——————-Salivation

Bell—-Food————-Salivation

REPEAT

Bell———————Salivation

THIS ASSOCIATION IS CONDITIONING

In technical terms, the meat powder is considered an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and the dog’s salivation is the unconditioned response (UCR). The bell is a neutral stimulus until the dog learns to associate the bell with food. Then the bell becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS) which produces the conditioned response (CR) of salivation after repeated pairings between the bell and food.

UCS—————- UCR

CS—UCS————-UCR

REPEAT

CS——————UCR

THIS ASSOCIATION IS CONDITIONING

Laws of Conditioning

Classical Conditioning is based on three laws:

- If the Conditioned Stimulus ( Bell ) is given after the Unconditioned Stimulus ( Food ) ,there will be no conditioning.

- If the Conditioned Stimulus ( Bell ) is given before the Unconditioned Stimulus ( Food ) ,the conditioning will sure to take place.

- If the Conditioned Stimulus ( Bell ) and the Unconditioned Stimulus ( Food ) ,is given simultaneously, the Conditioning may or may not take place.

If observed carefully the impact of Thorndike’s Law of Effect is clearly visible on these laws.

Other concepts / Empirical Relationships in Classical Conditioning:

Acquisition

Acquisition refers to the first stages of learning when a response is established. In classical conditioning, it refers to the period of time when the stimulus comes to evoke the conditioned response.

In classical conditioning, repeated pairings of the conditioned stimulus (CS) and the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) eventually leads to acquisition. Remember, the unconditioned stimulus is one that naturally evokes the unconditioned response (UCR). After pairing the CS with the UCS repeatedly, the CS alone will come to evoke the response, which is now known as the conditioned response (CR).

A number of factors can influence how quickly acquisition occurs. First, the salience of the conditioned stimulus can play an important role. If the CS is to subtle, the learner may not notice it enough for it to become associated with the unconditioned stimulus. Stimuli that are more noticeable usually lead to faster acquisition.

Contiguity

Timing plays a critical role. If there is too much of a delay between presentation of the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus, the learner might not form an association between the two. The most effective approach is to present the CS and then quickly introduce the UCS so that there is an overlap between the two. As a rule, the greater the delay between the UCS and the CS, the longer acquisition will take

Pavlov found that the shorter the time between the stimulus and the response, the more quickly a conditioned response could be developed. Ringing the bell immediately before giving food to the dog was more effective than ringing it some longer period of time before feeding. He referred to the time between stimulus and response as contiguity of the stimulus.

Stimulus Generalization

In conditioning, stimulus generalization is the tendency for the conditioned stimulus to evoke similar responses after the response has been conditioned. For example, if a child has been conditioned to fear a stuffed white rabbit, it will exhibit fear of objects similar to the conditioned stimulus such as a white toy rat.

Stimulus generalization can occur in both classical conditioning and operant conditioning. However, a subject can be taught to discriminate between similar stimuli and to only respond to a specific stimulus

Discrimination

In classical conditioning, discrimination is the ability to differentiate between a conditioned stimulus and other stimuli that have not been paired with an unconditioned stimulus.

For example, if a bell tone were the conditioned stimulus, discrimination would involve being able to tell the difference between the bell tone and other similar sounds.

Extinction

In psychology, extinction refers to the gradual weakening of a conditioned response that results in the behavior decreasing or disappearing.

In classical conditioning, this happens when a conditioned stimulus is no longer paired with an unconditioned stimulus.

Spontaneous Recovery

In classical conditioning, the reappearance of the conditioned response after a rest period or period of lessened response. If the conditioned stimulus and unconditioned stimulus are no longer associated, extinction will occur very rapidly after a spontaneous recovery.

For example, in Ivan Pavlov’s classic experiment, dogs were conditioned to salivate to the sound of a tone. Pavlov also noted that no longer pairing the tone with the presentation of food led to extinction of the salivation response. However, after a two hour rest period, the salivation response suddenly reappeared when the tone was presented.

Spontaneous recovery demonstrates that extinction is not the same thing as unlearning. While the response might disappear, that does not meant that it has been forgotten or eliminated.

Pavlov’s Position on problems of Education.-

Pavlov discussed on six typical problems:

- Capacity. The capacity to form conditioned reflexes is in part a matter of the type of nervous system; hence, there are some congenital differences in learning ability.

- Practice. In general, conditioned reflexes are strengthened with repetition under reinforcement, but care always has to be taken to avoid the accumulation of inhibition, for inhibition may appear even within repeated reinforcement.

- Motivation. In the usual reflexes, in which salivation is reinforced by food, the animal has to be hungry; drive is particularly important in the case of instrumental responses. Because of the “signalling” function of conditioned stimuli, it is presumed that some sort of drive reduction is usually involved; more contiguous stimulation does not appear to be the basis for learning although there is some lack of clarity on this point.

- Understanding .Subjective terms are to be avoided, so that Pavlov finds no use for terms such as understanding or insight. Yet his conception of reflex activity is so broad that he does not hesitate to say, “When a connection or association, is formed, this without doubt represents the knowledge of the matter, knowledge of definite relations existing in the external world, but when you make use of them the next time, this is what is called insight. In other words it means utilization of knowledge, utilization of the acquired connection”. This is the characteristic association’s view of understanding: the utilisation of past experience through some kind of transfer. The problem of novelty is not raised.

- Transfer. Transfer is best considered to be the result of generalization whereby one stimulus serves to evoke the conditioned reflex learned to another. Particularly in the language system, words substitute readily one for another, and thus permit wide generalization.

- Forgetting. Pavlov did not deal systematically with the retention or forgetting of conditioned reflexes overtime, partly because the same animals were used over and over again, there conditioned reflexes were greatly over learned, and forgetting was not laboratory problem. The decline of conditioned reflexes through experimental extinction, or other form of inhibition, was always recognised, and he always spoke of conditioned reflexes as temporary. I t is important to distinguish between extinction and forgetting, however, for there is spontaneous recovery following extinction and a weakened conditional reflex is therefore not a forgotten one.

Education Implication of Classical Conditioning:

Emphasis on behaviour: Students should be active respondents to learning, and in the learning process. They should be given an opportunity to actually behave or demonstrate learning. Secondly students should be assessed by observing behaviour, we can never assume that students are learning unless we can observe that behaviour is changing.

Drill and practice: the repetition of stimulus response habits can strengthen those habits. For example, some believe that the best way to improve reading is to have students read more and more. “Practice is important; Students should encounter academic subject matter in a positive climate and associate it with positive emotions; To break a bad habit, a learner must replace one S-R connection with another one (Exhaustion Method, Threshold Method, Incompatibility Method); and, Assessing learning involves looking for behaviour changes

Breaking habits: in order to break habits, that teacher needs to lead an individual to make a new response to this same old stimulus.