“Microteaching is defined as a system of controlled practice that makes it possible to concentrate on specified teaching behavior and to practice teaching under controlled conditions.”

- D.W. Allen & A.W. Eve (1968)

The modern age is leading towards the concept that the teachers are not born , but they can be made .The responsibility of producing competent teachers goes to the training institutions .Educational technology has played the key role in this job. Now the teacher’s behavior can be modified. In order to modify teacher’s behavior the technique can be effectively used.

.Getting in front of students is a trying experience for a budding teacher. One may earnestly try to prepare him or herself: read books about teaching methods, attend lectures and take courses on communication skill. Yet, in theory everything seems much simpler than in practice. The complexity of a teaching situation can be overwhelming. To deal effectively with it, teachers must not only have a good knowledge of the subject in hand, but also some communication skills such as ability to observe, supervise, lead a discussion and pose questions. Furthermore, a teacher should be aware of how students perceive him or her. This perception is sometimes quite different from the teacher’s self-image. It is difficult to self assess one’s own abilities and we benefit from colleagues’ feed back to recognize our strength and identify areas for possible improvement.

Evaluation of teaching by students is becoming a common practice, and a constructive feedback could be an effective way to improve one’s rating as a teacher. Even the experienced educators may sometimes reflect about strengths and weaknesses of their teaching style

What is microteaching

Microteaching is a scaled-down, simulated teaching encounter designed for the training of both pre-service or in-service teachers. Its purpose is to provide teachers with the opportunity for the safe practice of an enlarged cluster of teaching skills while learning how to develop simple, single-concept lessons in any teaching subject. Microteaching helps teachers improve both content and methods of teaching and develop specific teaching skills such as questioning, the use of examples and simple artifacts to make lessons more interesting, effective reinforcement techniques, and introducing and closing lessons effectively. Immediate, focused feedback and encouragement, combined with the opportunity to practice the suggested improvements in the same training session, are the foundations of the microteaching protocol.

The history of microteaching goes back to the early and mid 1960′s, when Dwight Allen and his colleagues from the Stanford University developed a training program aimed to improve verbal and nonverbal aspects of teacher’s speech and general performance. The Stanford model consisted of a three-step (teach, review and reflect, re-teach) approach using actual students as an authentic audience. The model was first applied to teaching science, but later it was introduced to language teaching. A very similar model called Instructional Skills Workshop (ISW) was developed in Canada during the early 1970′s as a training support program for college and institute faculty. Both models were designed to enhance teaching and promote open collegial discussion about teaching performance.

In the last few years, microteaching as a professional development tool is increasingly spreading in the field of teacher education.

Importance of Micro-teaching Program in teacher education program

Microteaching is an excellent way to build up skills and confidence, to experience a range of lecturing/tutoring styles and to learn and practice giving constructive feedback. Microteaching gives instructors an opportunity to safely put themselves “under the microscope” of a small group audience, but also to observe and comment on other people’s performances. As a tool for teacher preparation, microteaching trains teaching behaviors and skills in small group settings aided by video-recordings. In a protected environment of friends and colleagues, teachers can try out a short piece of what they usually do with their students, and receive a well-intended collegial feedback. A microteaching session is a chance to adopt new teaching and learning strategies and, through assuming the student role, to get an insight into students’ needs and expectations. It is a good time to learn from others and enrich one’s own repertoire of teaching methods.

Microteaching is an organized method of practice teaching which involves a small group of preceptors/instructors who observe each other teach, provide feedback and discuss with one another the strengths of their presentations and potential areas for improvement

Microteaching is so called since it is analogous to putting the teacher under a microscope so to say while he is teaching so that all faults in teaching methodology are brought into perspective for the observers to give a constructive feedback. It eliminates some of the complexities of learning to teach in the classroom situation such as the pressure of length of the lecture, the scope and content of the matter to be conveyed, the need to teach for a relatively long duration of time (usually an hour) and the need to face large numbers of students, some of whom are hostile temperamentally.

Microteaching also provides skilled supervision with an opportunity to get a constructive feedback. To go back to the analogy of the swimmer, while classroom teaching is like learning to swim at the deeper end of the pool, microteaching is an opportunity to practice at the shallower and less risky side.

Micro teaching makes the teacher education program ,more purposeful ,goal oriented and helps to decide common objectives for the program. It provides individualized training with more realistic evidence to students. Which enables them to develop competency in using specific teaching skills in view of their unique needs.

It provides a democratic type of behavior among faculty members and student-teachers.

It provides a facility of supervision which is not critical on threatening type, but is of a helpful and suggestive type ,which equip them for transition to school teaching. It is a system of controlled practice that makes it possible to concentrate on specific teaching behavior and to practice teaching under controlled conditions.

This way Micro teaching is a teacher education technique which allows teachers to apply clearly defined teaching skills to carefully prepared lessons in planned series to five to ten minutes encounters with a small group of real students ,often with an opportunity to observe the result on video-tape.

ASSUMPTIONS OF MICRO TEACHING

- Micro teaching can reduce the complexities of education. It simplifies the study of inter-action between the teacher and the students

- It can develop teaching skills. It provides an opportunity of integration of theory and practice. Specific skills can be developed

- It is completely an individualized training programme. It is a successful technique for individual training . It facilitates continuity in the training of the teachers

- It is real teaching. Micro-teaching technique is useful for both pre-service and in-service teachers

- It can control the practice by feedback. . Self evaluation is possible by tape recorder or video tape

- Feedback can be provided by various means, such as criticism by a teacher, preparing video film of the lesson, etc. There is provision of immediate and effective feedback

- Its objectives can be written more clearly and specifically

- Its use helps in the research work related to class-room teaching

COMPONENTS OF MICRO TEACHING

The involvement of the following component in micro teaching is necessary. In the absence of any component the success of this technique is doubtful.

1. Micro-teaching Situations. It consists of size of the class, length of the content and teaching method etc. There are 5 to 10 students in the class and the teaching period ranges from 5 to 20 minutes. The content is presented in a unit.

2. Teaching skill. The development of teaching-skills of the student’s teachers is provided in the training programme such as lecturing skill, skill of black-board writing, skill of asking questions etc.

3. Student Teacher .The student who. gets the training of a teacher is called student- teacher .During training his various capacities are developed in him, such as capacity of class management, capability of maintaining discipline and capacity of organizing various program of the school etc

.4. Feed-back Devices. Providing feedback is essential to bring changes in the behavior of the students. Feedback can be provided through videotape feed-back questionnaires

5. Micro Teaching Laboratory. Necessary facilities to feedback can be gathers in microteaching laboratory.

PHASES OF MICRO-TEACHING

Generally the micro-teaching is structured in three phases.

Phase one—Knowledge Acquisition Phase.

It is also known as modeling phase. Student-teacher is kept in conditions where observes model teacher who presents the teaching behavior to be learned. Inclusion of modeling in micro-teaching before actual practice is a pragmatic approach which foster the skill learning by student-teachers, as learning by observation is said to occur through informative function of modeling.

Phase two-Skill Acquisition phase

It is also known as practicing phase. Student-teacher are given opportunity in real classroom situations, but scaled down, to practice the same behavior or skill.

Phase three-Transfer Phase-

It is also known as feedback phase. Student-teachers are reinforced for those instances of desired behavior they have acquired and have provision for feed-back for developing the desired behavior or skill up to the mark.

OPERATIONS IN MICRO-TEACHING

1. Analysis of a skill in behavior terms i.e. .objectives of the skill be clear.

2. A demonstration of the skill on video tape or films or in normal classroom teaching.

3. Trainee plans a short lesson in the subject of his interest in which he can use the skill

4. Trainee teaches the lesson to a small group of students (5-10) which is observed directly or video taped or audio taped.

5. Feedback is provided to trainee or discussing and analyzing his performance with the help of supervisor. If the skill has been used effectively, trainee is reinforced and if there is any drawback the skill would have been exercised by giving suggestions to him

6. Feedback or supervisor’s remarks develop insight in the trainee. He replants the lesson to use the skill more efficiently.

7. Revised lesson is retaught to different but comparable groups.

8. Feedback is again provided on retaught lesson which is annualized with the help of the supervisor.

STANDARD PROCEDURE OF MICRO-TEACHING

The following steps are recommended for a successful micro-teaching session – eaching among teacher-educators and student teachers

Step one – Orientation- Theoretical background, merits and demerits of micro- teaching may be arranged.

Step Two- Discussion of Teaching Skills.-Concept of teaching skills should be cleared. At least, five teaching skills should be selected and explained at length with the help of handbooks developed by competent authorities. One skill at a time may be discussed before practice.

Step Three- Presentation of Model Lesson – Model lesson of corresponding skills is demonstrated by the trained teacher educator in selected subjects to the student teacher.

Step Four.-Presentation of Micro lesson plan.-Student-teacher selects one topic or unit for micro-lesson and prepare the lesson plan logically.

Guidelines for Presentation

- Structure presentation: Give an introduction to the topic, mention the key points and summarize the topic at the end of the presentation

- Encourage audience participation: Ask questions and create ways for interaction with the audience

- Translate enthusiasm for the topic: Grab the audience’s attention at the beginning of the topic by opening with quotes/ important statistics/ clinical findings etc., pause and emphasize important points

- Use props: OHPs, PowerPoint or the board can be used to organize your presentation, include illustrations and emphasize the main points

- Practice presentation prior to the workshop: Practice in front of the mirror or a colleague , practice aloud and notice your body language, gestures and facial expressions, rehearse your presentation to fit in the 5 minute slot

- Review the microteaching feedback form: The criteria peers will be using in their feedback will help to perfect delivery technique. Keep the voice loud and clear, maintain eye contact with the audience, pace an unhurried presentation

The Presentation

Participants of the microteaching session prepare a ‘microlesson’ for 5 minutes to be addressed to a ‘micro-class’ comprising of a small group of peers and a facilitator.

To plan a 5 minute lesson of your choice, present it before a small group of peers who will role play the students in your class and then give you feedback on your presentation with the intention of improving your presentation and teaching skills

And so on… At the end of the session, the student-teacher will have:

- Reflected on how best he/her can teach

- Perceived he/her strengths

- Enhanced he/her understanding of various effective teaching styles c

- Identified areas for improvement

- Improved he/her ability to provide and receive effective feedback

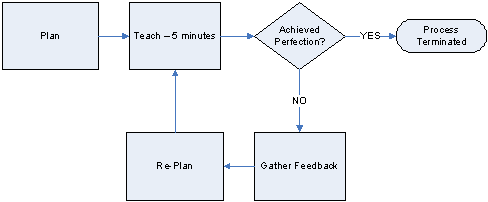

The components of the microteaching cycle are shown in Figure. The Microteaching cycle starts with planning. In order to reduce the complexities involved in teaching, the student teacher is asked to plan a “microlesson” i.e a short lesson for 5-10 minutes which he will teach in front of a “micro-class” i.e. a group consisting 5–10 students, a supervisor and peers if necessary. There is scope for projection of model teaching skills if required to help the teacher prepare for his session. The student teacher is asked to teach concentrating one or few of the teaching skills enumerated earlier. His teaching is evaluated by the students, peers and the supervisor using checklists to help them. Video recording can be done if facilities permit. At the- end of the 5 or 10 minutes session as planned, the teacher is given a feedback on the deficiencies noticed in his teaching methodology. Feedback can be aided by playing back the video recording. Using the feedback to help himself, the teacher is asked to re-plan his lesson keeping the comments in view and ret each immediately the same lesson to another group. Such repeated cycles of teaching, feedback and re-teaching help the teacher to improve his teaching skills one at a time. Several such sequences can be planned at the departmental level. Colleagues and postgraduate students can act as peer evaluators for this purpose. It is important, however, that the cycle is used purely for helping the teacher and not as a tool for making a value judgment of his teaching capacity by his superiors.

Step Five.-Micro-teaching setting.-To set up micro-teaching following variables should be taken into considerations.-

A. Time ;36 minutes.

B. Number of students ;8—10.

C .Supervisor s; one or two

D. Teaching technique of feedback by superior video or audio or supervisor himself

Step six-Simulated conditions- Peers should act as pupils. Microteaching is conducted in the training college itself.

Step Seven- Practice of teaching skills.- At least five skills may be practiced by a student teacher at one time. Any of the five may be selected from the following list of teaching skills.-

- Probing questions.

- . Stimulus Variation.

- .Reinforcement.

- .Silence and nonverbal cues.

- . Illustrating with examples.

- Encouraging students participation.

- . Explaining.

- . Effective use of black-board.

- Set induction.

- . Closure.

Step eight-Observation of teaching skill-is done by peers and supervisors

For the purpose of providing feedback to the student -teacher ,the felicitator can use the following criteria (in the form of observation schedule )

Duration of presentation -It should be Approx. 10 minutes .The Start time…….Finish time……..and the .Total duration………..minutes be noted down

Comprehensibility – The felicitator should observe whether -

- The presentation was be given in comprehensible language

- The presentation is sufficiently comprehensible.

Comprehensibility should be improved

Visualization – – The felicitator should see whether the presentation was accompanied by selected elements of visualization ,or the following forms of visualization have been used:

- slides

- handouts for the participants

- pin board

- flipchart

- white/black board

He/she should see whether the visual elements assist the understanding, the visual elements needs improvement.

Density of information – The felicitator should see whether the density of information should be high. However, it must not overtax the learner The density of information seems to demand too much of the learner. He/she should see whether the

Characteristics of a good quality presentation. The felicitator should tick Yes or No when assessing)Whether the presentation comprehensible?

The felicitator should tick Yes or No when assessing)Whether Is the presentation stimulating-

- visualization is clear and well-structured

- includes graphic elements and optical stimuli-

- easily legible writing

- colors help to focus on the important aspects

- comprehensible visualization

- affectionate layout

- eye contact-

- speaker varies his position

- participants are encouraged to contribute-

- use of humor to create a relaxed atmosphere

- presented with commitment-

- friendly/respectful behavior

Step nine – Immediate feedback is given to student –teachers.Tallies and ratings by peer groups and supervisors may be used for interpretation and feed-back about the performance of student-teacher.

The feedback

Under the guidance of the professional supervisor, the presenter is first asked to present a self feed back of his mini lesson. With this new information taken into account, the supervisory team member who volunteered to be the speaker summarizes the comments generated during the analysis session. This part of the session is intended to provide positive reinforcement and constructive criticism. The presenter is encouraged to interact freely with the team so that all comments are clarified to his/her satisfaction.

The way in which feedback is given and received contributes to the learning process. Feedback should be honest and direct, constructive, focusing on the ways the presenter can improve, and containing personal observations.

The following is a series of suggestions on how to give and receive feedback in a microteaching workshop.

Providing feedback

When you are giving feedback, try to develop the skill to give an effective feedback:

Be respectful, give a specific but detailed comment, start on a positive note, do not be judgmental, maintain collegiality, listen and speak in turn, so that everyone can hear all the comments, complete the Microteaching Feedback Form

Be descriptive and specific, rather than evaluative. For example: you would avoid starting the sentences with “you”, it is better to start with “I”, so you can say: “I understood the model, after you showed us the diagram”.

Begin and end with strengths of the presentation. If you start off with negative criticism, the person receiving the feedback might not even hear the positive part, which will come later.

Be specific rather than general. For example: rather than saying “You weren’t clear in your explanations”, tell the presenter where he/she was vague, and describe why you had trouble understanding him/her. Similarly, instead of saying: “I thought you did an excellent job!”, list the specific things that he/she did well.

Describe something the person can act upon. Making a comment on the vocal quality of someone whose voice is naturally high-pitched is only likely to discourage him/her. However, if the person’s voice had a squeaky quality because he/she was nervous, you might say: “You might want to breath more deeply, to relax yourself, and that will help to lower the pitch of your voice as well”.

Choose one or two things the person can concentrate on. If the people are overwhelmed with too many suggestions, they are likely to become frustrated. When giving feedback, call attention to those areas that need the most improvement.

Avoid conclusions about motives or feelings. For example: rather than saying: “You don’t seem very enthusiastic about the lesson”, you can say “Varying your rate and volume of speaking would give you a more animated style”.

Receiving feedback

When receiving feedback, try to listen to feedback given during the session: Listen to and acknowledge the positive feedback that so as to focus on the strengths and work on the weaknesses

Be open to what you are hearing. Being told that you need to improve yourself is not always easy, but as we have pointed out, it is an important part of the learning process. Although, you might feel hurt in response to criticism, try not to let those feelings dissuade you from using the feedback to your best advantage

Not to respond to each point, rather listen quietly, hearing what other’s experiences were during their review, asking only for clarification. The only time to interfere with what is being said is if you need to state that you are overloaded with too much feedback.

Ask for specific examples if you need to. If the critique you are receiving is vague or unfocused, ask the person to give you several specific examples of the point he/she is trying to make

Take notes, if possible. If you can, take notes as you are hearing the other people’s comment. Than you will have a record to refer to, and you might discover that the comments that seemed to be the harshest were actually the most useful.

Judge the feedback by the person, who is giving it. You do not have to agree with every comment. Ask other people if they agree with the person’s critique

Step ten.-Discussion and Analysis

While the presenter goes to another room to view the videotape, the supervisory team discusses and analyses the presentation. Patterns of teaching with evidence to support them are presented. The discussion should focus on the identification of recurrent behaviors of the presenter in the act of teaching. A few patterns are chosen for further discussions with the presenter. Only those patterns are selected which seem possible to alter and those which through emphasis or omission would greatly improve the teacher’s presentation. Objectives of the lesson plan are also examined to determine if they were met. It is understood that flexible teaching sometimes includes the modification and omission of objectives. Suggestions for improvement and alternative methods for presenting the lesson are formulated. Finally, a member of the supervisory team volunteers to be the speaker in giving the collected group feedback.-Complete cycle of a micro-lesson by a trainee will take about 35 minutes to be completed.

Precautions in micro-teaching application

- Clarity of objectives is a must.

- Micro-lesson plan should be prepared for one skill only at a time.

- Delivering model lessons is essential.

- Before teaching the student-teacher must prepare his micro-lesson plan.

- Substantial suggestions should also accompany criticism in order to improve the teaching skill of the student-teachers.

Advantages of micro-teaching

Microteaching has several advantages. It focuses on sharpening and developing specific teaching skills and eliminating errors. It enables understanding of behaviours important in classroom teaching. It increases the confidence of the learner teacher. It is a vehicle of continuous training applicable at all stages not only to teachers at the beginning of their career but also for more senior teachers. It enables projection of model instructional skills. It provides expert supervision and a constructive feedback and above all if provides for repeated practice without adverse consequences to the teacher or his students.

A microteaching session is much more comfortable than real classroom situations, because it eliminates pressure resulting from the length of the lecture, the scope and content of the matter to be conveyed, and the need to face large numbers of students, some of whom may be inattentive or even hostile. Another advantage of microteaching is that it provides skilled supervisors who can give support, lead the session in a proper direction and share some insights from the pedagogic sciences.

The techniques of micro teaching is a new experiment in the field of education. It has the following advantages

- It promotes analysis of behavior of the teacher It is an effective way of instilling confidence in the teacher in planning and implementation of the lesson plan

- It helps create a conducive ambience in the classroom .It can be used in the college. The pupil teacher needs not to go to any school for the training of teaching skills.

- It focuses on honing teaching skills through participation and observation The number of students as well as duration of teaching is less.

- It empowers teachers with diverse teaching methods The content is divided into smaller units which makes the teaching easier.

- The problem of indiscipline can also be controlled. The other class- mates of pupil teacher can also supervise the task of teaching.

- There is a provision of immediate feedback.

- Only one teaching skill is considered at a time. There is a facility of re-planning, re-teaching and re-evaluation.

- There are occasions of comparing two or more teaching behaviors of the pupil teachers.

Limitations of Micro-Teaching

Lack of adequate and in-depth awareness of the purpose of microteaching has led to criticisms that microteaching produces homogenized standard robots with set smiles and procedures. It is said to be (wrongly) a form of play acting in unnatural surroundings and it is feared that the acquired skills may not be internalized. However, these criticisms lack substance. A lot depends on the motivation of the teacher to improve himself and the ability of the observer to give a good feedback. Repeated experiments abroad have shown that over a period of time microteaching produces remarkable improvement in teaching skills.

The arrangement of micro teaching laboratory is very expensive in small training colleges. Video, tape recorder and other devices are required in making the lesson effective. It is not possible for all training colleges to make such arrangements.

This technique is not complete in itself. It is useful only if it is used along with other techniques, such as inter action analysis method and stimulated teaching method.The teachers also need the training of this method.

REFERENCES/

1. ALLEN, D.W. et.al. Micro-teaching – A Description. Stanford University Press, 1969.

2. ALLEN, D.W , RYAN, K.A. Micro-teaching Reading Mass.: Addison Wesley, 1969.

3. GREWAL, J.S., R. P. SINGH. “A Comparative Study of the Effects of Standard MT With Varied Set of Skills Upon General Teaching Competence and Attitudes of Pre-service Secondary School Teachers.” In R.C. DAS, et.al. Differential Effectiveness of MT Components, New Delhi, NCERT, 1979.

4. PASSI, B.K., Becoming Better Teachers. Baroda : Centre for Advanced Study in Education, M. S. University of Baroda, 1976.

5. SINGH, L. C. et.al. Micro-teaching – Theory and Practice, Agra : Psychological Corporation, 1987..

8. VAIDYA, N. Micro-teaching : An Experiment in Teacher Training. The Polytechnic Teacher, Technical Teacher, Technical Training Institute, Chandigarh, 1970.

Mrs. Rakhi Maheshwari and Miss Nisha Rani Vishnoi for being the scribe of this article.

The four characteristics of humanism are curiosity, a free mind, belief in good taste, and belief in the human race.

The four characteristics of humanism are curiosity, a free mind, belief in good taste, and belief in the human race.