Existentialism is the most individualistic of all modern philosophies. Its overriding concern is with the individual and its primary value is the absolute freedom of the person, who is only what he makes himself to be, and who is the final and exclusive arbiter of the values he freely determines for himself. Great emphasis is placed on art, on literature, and the humanistic studies, for it is in these areas that man finds himself and discovers what values he will seek to attain.

Existentialism is the most individualistic of all modern philosophies. Its overriding concern is with the individual and its primary value is the absolute freedom of the person, who is only what he makes himself to be, and who is the final and exclusive arbiter of the values he freely determines for himself. Great emphasis is placed on art, on literature, and the humanistic studies, for it is in these areas that man finds himself and discovers what values he will seek to attain.

Existentialism represents a protest against the rationalism of traditional philosophy, against misleading notions of the bourgeois culture, and the dehumanizing values of industrial civilization. Since alienation, loneliness and self-estrangement constitute threats to human personality in the modern world, existential thought has viewed as its cardinal concerns a quest for subjective truth, a reaction against the ‘negation of Being’ and a perennial search for freedom..

Existentialism is a 20th century philosophy concerned with human existence, finding self, and the meaning of life through free will, choice, and personal responsibility. The belief that people are searching to find out who and what they are throughout life as they make choices based on their experiences, beliefs, and outlook without the help of laws. Existentialism then stresses that a person’s judgment is the determining factor for what is to be believed rather than by religious or secular world values.

Existentialism is a term applied to the work of a number of 19th- and 20th-century philosophers who, despite profound doctrinal differences, generally held that the focus of philosophical thought should be to deal with the conditions of existence of the individual person and his or her emotions, actions, responsibilities, and thoughts. The early 19th century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, posthumously regarded as the father of existentialism, maintained that the individual solely has the responsibilities of giving one’s own life meaning and living that life passionately and sincerely, in spite of many existential obstacles and distractions including despair, angst, absurdity, alienation, and boredom.

Subsequent existential philosophers retain the emphasis on the individual, but differ, in varying degrees, on how one achieves and what constitutes a fulfilling life, what obstacles must be overcome, and what external and internal factors are involved, including the potential consequences of the existence or non-existence of God. Existentialism became fashionable in the post-World War years as a way to reassert the importance of human individuality and freedom

“Another very significant source of confusion arises out of the different personal lives and convictions of existential philosophers. Kierkegaard, Marcel and Jaspers are theists whereas Sartre and Heidegger are agnostics. Jaspers is a protestant whereas Marcel is a staunch Roman Catholic. Less said the better about the diversities of other existentialist philosophers like Berdyaev, Buber, Tillich and Niebuhr.”

Historical Retrospect-:

Just as the whole of Indian philosophy is an extension, interpretation, criticism and corroboration of the Vedas and in it the Upanishads or an outright revolt against them, similarly it may be remarked of western philosophy as either a clarification of Socrates or his rejection. One would be still right in saying that the whole of western philosophy is an appendix on Socrates. So it is even true with existentialism that Socrates has been considered to be the first existentialist. Socrates statement: “I am and always have been a man to obey nothing in my nature except the reasoning which upon reflection, appears to me to be the best.” Right from Plato down to (Spinoza, Leibnitz) Descartes, the majority of western thinkers have been believing in the immutability of ideas and the rest of the thinkers have been suggesting correctives to it. Anyhow their frame of reference has always been ‘Essence Precedes Existence’, essence being referred to ideas, values, ideals, thoughts, etc. and existence being referred to our lives. The last in the series was Hegel who carried farthest this effort to understand the world rationally

19th century

At least for the western world, the first half of the twentieth century has been an age marked by anxieties, conflicts, sufferings, tragic episodes, dread, harrow, anguish, persecution and human sacrifices caused by the two intermittent world wars. As Harper writes : “Tragedy, death, guilt, suffering all force one to appraise one’s total situation, much more than do happiness, joy, success, innocence, since it is in the former that momentous choices must be made.” So, there sprang up a group of philosophers spread all over Germany, France and Italy which were the places of social crisis.

Significant among these philosophers were Karl Jaspers and Martin Headgear from Germany. France contributed two other existentialists -: Gabriel Marcel and Jean Paul Sartre. ‘There are quite a few gentlemen who are associated remotely with the philosophy of existentialism like Schelling, Nietzsche, Pascal, Husserl who have influenced existential thought but cannot be rigidly classified as existentialists.” Existentialism thus has a short history of nearly two centuries.

Kierkegaard and Nietzsche

Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche were two of the first philosophers considered fundamental to the existentialist movement, though neither used the term “existentialism Kierkegaard’s knight of faith and Nietzsche’s Übermensch are exemplars who define the nature of their own existence. These idealized individuals invent their own values and create the very terms under which they excel.

Dostoyevsky and Kafka

Two of the first literary authors important to existentialism were the Czech Franz Kafka and the Russian Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky’s portrays a man unable to fit into society and unhappy with the identities he creates for himself.

Early 20th century

In the first decades of the 20th century, a number of philosophers and writers had explored existentialists ideas,. The Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo, , emphasized the life of “flesh and bone” as opposed to that of abstract rationalism. Another Spanish thinker, Ortega y Gasset, held that the human existence must always be defined as the individual person combined with the concrete circumstances of his life: ”

Two Russian thinkers, Lev Shestov and Nikolai Berdyaev became well-known as existentialist. Gabriel Marcel, long before coining the term “existentialism”, introduced important existentialist themes to a French audience In Germany, the psychologist and philosopher Karl Jaspers — who later described existentialism as a “phantom” created by the public called his own thought, heavily influenced by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche — Existenzphilosophie.

After the Second World War

Following the Second World War, existentialism became a well-known and significant philosophical and cultural movement, mainly through the public prominence of two French writers, Sartre and Albert Camus, who wrote best-selling novels, plays and widely-read journalism as well as theoretical texts. These years also saw the growing reputation outside Germany of Heidegger’s book Being and Time.

Paul Tillich, an important existential theologian following Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Barth, applied existential concepts to Christian, and helped introduce existential theology to the general public.

Meaning and Definition of Existentialism

There is a wide variety of philosophical ideologies that make up existentialism so there is not a universal existentialism definition. It is necessary to remain open and realize that most existentialists have a different view and form

The term “existentialism” seems to have been coined by the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel in the mid-1940sand adopted by Jean-Paul Sartre, on October 29, 1945

Etymological meaning of ‘existence’ from two German words -: ‘ex-sistent’ meaning that which stands out, that which ‘emerges’ suggests that existentialism is a philosophy that emerges out of problems of life.

As a term, ‘Existentialism’ appears to refer to a unified school of thought, but this is a problematic assumption, because it is derived from a variety of existential philosophers. Amongst the best known are Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger and Sartre. Other important contributors include Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, Paul Tillich, Martin Buber, Miguel de Unamuno and writers of literature such as Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Franz Kafka and Joseph Conrad. ‘Existentialism’ refers to the common themes found amongst these and other thinkers, and is able to stand as a recognized integrated system of philosophy in its own right

Since its introduction by Gabriel Marcel in the post-war period, ‘Existentialism’ has suffered from various interpretations and misinterpretations to such a degree that even Sartre wrote that “the word [existentialism] is now so loosely applied to so many things that it no longer means anything at all”. As a term, it is derived from the word existence, implying that the individual has presence-in-the-world. Heidegger included the hyphen in his term Ek-sistenz to accentuate the Greek and Latin origins which mean ‘to stand out from’, and applied it to mean that the individual stands out from, or beyond, his or her present. He described this as ‘possibilities’ or ‘ways to be’, and explained it as, “The analysis of the characteristics of the being of Da-sein is an existential one. This means that the characteristics are not properties of something objectively present, but essentially existential ways to be Heidegger used the term existential to refer to the structure of the individual in general. He designated his term existentiell to mean self-understanding, how an individual understands himself or herself. But this self-understanding is only possible through existence itself, as Heidegger often emphasized the practicality of his lived philosophy. He argued that “We come to terms with the question of existence always only through existence itself. We shall call this kind of understanding of itself existentiell understanding”.

Blackham has described existentialism as a philosophy of being “a philosophy of attestation and acceptance, and a refusal of the attempt to rationalize and to think Being.”, “it deals with the separation of man from himself and from the world, which raises the question of philosophy not by attempting to establish some universal form of justification which will enable man to readjust himself but by permanently enlarging and lining the separation itself as primordial and constitutive for personal existence.”

Harries and Leveys defined existentialism as “any of several philosophic systems, all centered on the individual and his relationship the universe or to God.”

Tiryakian defines it as “an attempt to reaffirm the importance of the individual by rigorous and in many respects radically new analysis of the nature of man.”

In the opinion presented here, existentialism is a humanistic perspective on the individual situation, a philosophy of existence, of being, of authenticity and of universal freedom. It is a quest, beyond despair, for creative identity. It is the philosophy that is a counselor in crisis, “a crisis in the individual’s life, which calls upon him to make a ‘choice’ regarding his subsequent existence.”

Philosophical Rationale of Existentialism

Rather than attempt to define existentialism (which existentialists themselves maintain is futile) it might to be better to determine what the task of philosophy is according to the proponents of this school of thought. First of all, the existentialist does not concern himself with problems concerning the nature, origin, and destiny of the physical universe. The philosopher should not even concern himself with the basic assumptions of the physical or biological sciences.

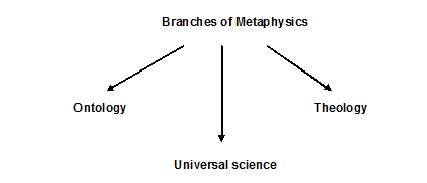

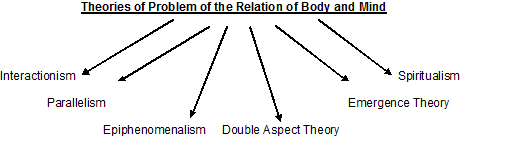

Metaphysical Position

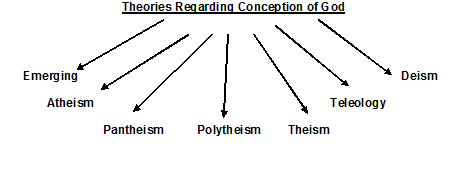

Concept of God-

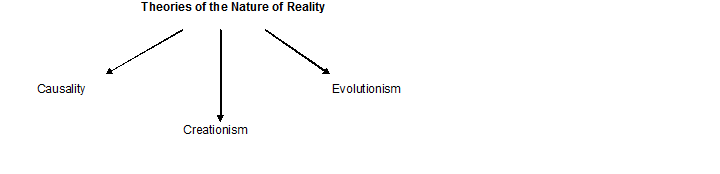

There are two forms of existentialism: (1) theistic existentialism, and (2) atheistic existentialism.

According to theistic existentialism (e.g., Kierkegaard, Heidegger), God has created us & yet has also apparently withdrawn from Her creation–so that we find ourselves bereft of divine guidance & lost in the world & questioning our faith. Then in the face of a seemingly meaningless, pointless world, individuals must create meaningful lives for themselves by making active choices and by taking full responsibility for those choices.

According to atheistic existentialism, “God is dead.” This is because the very idea of God contains a tragic incoherence:

Assume that God exists and is all-powerful & all-knowing & all-good. Then also assume that evil exists in the world. Then God is either responsible for the existence of evil, in which case God is Himself evil & not all-good; or else God is not responsible for the existence of evil & yet knew that it was going to happen & couldn’t prevent it–so God is not all-powerful; or else God would have prevented evil but didn’t know it was going to happen, and is therefore not all-knowing. So given evil, God is either not all-good, not all-powerful, not all-knowing, or does not exist.

The atheistic existentialist then concludes that God does not exist. What this means is that human beings have no pre-established nature or essence or goal for their lives, and that in the face of a meaningless pointless world, individuals must create meaningful lives for themselves by making active choices and by taking full responsibility for those choices

Frederic Nietzsche’s statement, “God is dead,” succinctly expresses the atheistic existentialist’s view on the issue of the existence of a supernatural realm. Neither Nietzsche, Heidegger, nor Sartre makes any attempt to refute the traditional arguments for the existence of God presented by the scholastics or those who use the “ontological argument.” Rather, they simply begin with the assumption that God does not exist and proceed to construct their philosophical views on the postulate. Nietzsche says: Where is God gone ?…. I mean to tell you! We have killed him – you and I !….. Do we not here the noise of the grave – diggers who are burying God? God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed! …. The holiest and the mightiest that the world has hitherto possessed had bled to death under our knife – …. What are our churches now, if they are not the tombs and monuments of God?

Martin feels that man does not need to seek answers in divine revelation since philosophy can solve the basic riddles of human existence. For Heidegger, then, the existence or nonexistence of God and supernatural values is irrelevant to man’s major task, that of creating himself.

, Sartre maintains that man can never comprehend the true meaning of his own existence unless he presupposes there is no God. For when we being with the premise that there is God, then we must conclude that man possesses an essence which precedes personal existence

Thus Sartre rejects classical atheism which suppresses the idea of God but retains the notion that men possess a common, rational mature or essence. This position, Sartre believes, is inconsistent with atheism because it retains all the significant elements of theism and refuses to accept the individual responsibility for self-creation which all true atheism implies.

Concept of Self

The very question of the nature of man is a meaningless one for the existentialist. In both of the sections above it was emphasized that man has no “nature” as such but rather that he must create his own essence. Man is nothing more than what he makes or himself. Perhaps, then, it might be more accurate to speak of certain characteristics, state, or conditions which man creates for himself or into which he is thrown.

The most important of these characteristics is freedom. Man is condemned to freedom. “Human freedom is not a part of human existence, “Sartre says, “it precedes human existence and makes it possible. The freedom of man cannot be separated from the being of man. It is the being of man’s consciousness. It is not a human attribute but is the raw material of my being. I own my being to my freedom.”

Man, then, does not possess free will as a part of his essential mature, but rather he exists in a state of absolute freedom The centre of existence is man rather than truth, laws, principles or essence.

The uniqueness of man comes from his emotions, feelings, perception and thinking. The philosophy of existentialism stresses meaning, only through development of meaning in his life, man can make something of the absurdity which surrounds him. Man is the maker, and, therefore, the master of culture. It is man who imposes a meaning on his universe, although that universe may well function without him. Man cannot be ‘taught’ what the world is about. He must create this for himself.

Nature of society

Man is not alone in the world.He is connected to other men; he communicates with others; therefore, he cannot live in a state of anarchy. Life is seen as a gift, which, in part is a mystery. Man is free to choose commitments in life, in his choice, he becomes himself. He is the product of his choices. He is, therefore, an individual who is different from other persons. The real living person is more important than any statement we can make about him. Man’s existence is more important than his essence are considered strong enough (by the existentialist) to impair man’s freedom.

The task of defining the nature of society is much more difficult than, it was for other philosophies Man’s place is society and the effects of society on man’s nature are clearly spelled out.. If man has no predetermined nature, certainly society must have none. In other words, there is no place in existentialist philosophy for social theory as developed within the other philosophies The existentialist often is accused of being “antisocial” in his behavior as well as in his philosophy. if existentialists have no theory of society, it might be more accurate to ask how they view other men. First, they would grant to others the same existential freedom which they demand for themselves. That is, man is never to be viewed as a means but rather as an end..

Second, individual man is not bound to other men by any predetermined notion of brotherhood or by allegiance to a certain group. On the contrary, each man should express his freedom in the creation of his own selfhood, first by “withdrawing from the crowd,” and then by communicating only with those whom he personally chooses as kindred spirits. Sartre is most emphatic on this point. He carries to its logical conclusion Kierkegaard’s fight for the individual against the crowd, social institutions, or the system. Sartre feels that the entire network of social life is anti-individual. Churches, schools, political parties, and even the family tend to militate against man’s absolute freedom.

This antisocial outlook seems to be one of the facets of existentialism which the “lunatic fringe” of the movement has given major emphasis they dislike attending formal educational institutions since these, too, limit one’s freedom by holding the student to very specific requirements, class attendance, examinations, and the like. To summarize, the main points in the existentialist beliefs about the nature of man and society hinge on the basic assumption that man is absolute freedom. This existential freedom generates anguish, abandonment, and despair. Because man is a lonely being, he cannot seek solace in social relations but must choose and act as an individual rather than as a member of society. A person who will and acts in accordance will the notion of absolute freedom will never be swayed by the “will of the mob” or by the demands of social institutions. He will do as he wishes; he will create himself “according to his image and likeness

Epistemological Position

Existentialists, have given little attention to inductive reasoning. Science, they believe, has been on of the major dehumanizing forces in the modern world. It is not that existentialists want to put an abrupt halt to all scientific work. Rather, they argue, the philosopher should not concern himself with such matters. It should be quite evident from the section above that “philosophizing” is performed on such topics as the nature and importance of freedom, man’s metal states, decisions, and action.

The existentialist approach to philosophy, then, calls for a new epistemology. This new approach to knowledge is known as the phenomenological method. The atheistic existentialists inherited this method from Husserl. It was adapted further by Heidegger and Sartre to suit their philosophy of “will and action,” especially as it concerns the individual.. The phenomenological method consists in the expression of the experiences of consciousness through the media of ordinary language

Clearly, then, existentialism is not so concerned as are other modes of thinking with the kind of knowledge found in the empirical sciences. Such knowledge is not concerned with choices of values, modes of living, and acting.

In opposition to this cold impersonal approach to knowledge, the existentialist argues that true knowledge is “choosing, actions, living, and dying.” Let the scientist continue his pursuit of cold, lifeless fact and theory, but let the philosopher concerns himself with the aspects of the world which involve personal true humanism.

Axiological Position

The idea of the highest ehthical good can be found in philosophy since the days of Socrates and Plato. It was generally held that this good was the same for everybody; as a person approached this moral perfection, she/he became morally like the next person approaching this moral perfection. Kierkegaard reacted to this way of thinking by saying that it was up to the individual to find his or her own moral perfection and his or her own way there. “I must find the truth that is the truth for me. . .the idea for which I can live or die” he wrote. Other Existentialists have followed along this way of thinking, one must choose one’s own way, make their own individual paths without the aid of universal ideas or guidance

Existential ethics

Existentialism is also the basis of an ethics. According to existential ethics the highest good for humans is “becoming an individual) or “authenticity” = psychological coherence + integrity = not merely being alive but having a real life by being true to yourself

Authenticity & human freedom Existentialists have a special connotation of the Authentic man According to the existentialists, becoming authentic allows one to determine how things are to count towards one’s situation and how one is to act in relation to them. This term ‘authentic’ is derived from the Greek autos, referring to ‘one who does a thing for himself’. Derived from this is the German eigen meaning to ‘own’, and by implication, ‘to have, possess’.

Generally the existentialists consider authentic individuals to take responsibility for determining and choosing possibilities and not to simply become a determined product of a cultural moment. Heidegger stated that the ‘existentia’ has priority over the ‘essentia’, and this view has been made popular through the works of Sartre,. By living authentically, one can choose one’s own identity and possibilities rather than have these dictated by the crowd Freedom, or the human ability to make choices and take responsibility, determines authenticity. Thus the act of choice is an act of self-creation: we are nothing but we make of ourselves.

Freedom in the existential sense entails that at least sometimes you must take full responsibility for things over which you have no control. So what you ought to do, or what is morally right, , is to choose a particular way of life, and to take full responsibility for that life

Inauthenticity & human unfreedom The failure to choose in this way, or the failure to take full responsibility for one’s choices, is “inauthenticity” = psychic incoherence + lack of integrity Accordingly, the worst thing of all is inauthenticity & unfreedom, so it is morally impermissible.

From what has been said above in connection with the nature of man and the knowing process it is quite evident that the atheistic existentialist cannot subscribe to any value theory which purports to be objective, absolute, universal, or social. If there were a preexistent moral law which detailed general or specific behavioral patterns for all men, true existential freedom would be mockery as well as an impossibility. Also, since man himself has no specific or evil,” one cannot argue that a good man will make certain since society has no independent existence it cannot claim any rights over the moral choice and behavior of individuals. Values, then, do not exist except in conjunction with the freely chosen acts of individuals.

Truly, it is because of his lack of an external moral authority that he individual finds himself in the states of anguish, abandonment, and despair. In fact, even those individuals who have committed themselves to the assumedly “objective systems” of morality have done so for their own free choice. They have not made this choice because these ethical system are “objective”; rather, by choosing this or that code of behavior they have “objectified” for themselves their own subjective choices.”

All choices must be good, at least for the nonce. At a later date, one might regret having made such a choice but that is beside the point. The very essence of good is choosing. It seems them, that man never chooses evil. If one makes no choice one is not creating his own essence. This is how animals behave – their masters choose for them. But animals are not free so they cannot be accused of good or evil. But man, who is “condiment to freedom,” must choose if he wishes to consider himself more than an animal. A man “becomes a man” when he makes choice. When he makes choices he creates his own values. When he creates his own values, he creates his own being or essence.

Existential Aesthetics.

The existentialist, , considers the development of aesthetic theory as one or the major concerns of the philosopher.

Another distinctive feature of the aesthetical views of existentialists lies in their use of he art forms, especially literature, drama, and painting, as media for communicating philosophical doctrines. The history of philosophy records no parallel of a school of thought which uses the arts as the avenue for putting their beliefs into the cultural steam of the age.

Fundamental Postulates of Existentialism

The existentialist movement is based on an intellectual attitude that philosophers term existentialism

Permanence and Change

The philosophy of Aristotle and the scholastics explains change in such a way that change is impossible without something stable which endures throughout the process of change. When a child change to a man, becomes a man, there is continuity of past with present, as it is the same person who once was a child and is now a man. In his essence as rational animal the child-become-a-man abides. Existence then is not prior to essence; man is born with an essence. As soon as he exists he has a predetermined essence.

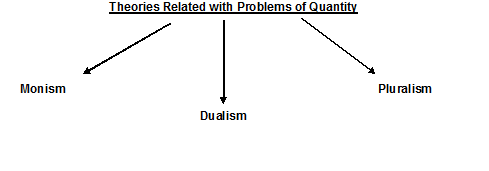

The existentialists, on the contrary, deny the preeminence of essence. They reject the notion that there is a predetermined nature for every human being. Man is not born with a rational soul which “forms the matter,” the body. Man has no essence at birth; he must create his own essence. And with Darwin, the existentialist would concur that no living beings will remain the same – all are in the process of changing. Consequently, existentialism is to be classified as one of the philosophies of change..

If man as the existentialist sees him is not definable it is because to begin wit he is nothing. He well not be anything until later, and then he will be what makes himself. Thus, there is no human nature, because there is no God to have a conception of it. Man simply is. Not that he is simply what he conceives himself to be, but he is what he wills, and as he conceives himself after already existing – as he wills to be after that leap towards existence. Man is nothing else but that which he make himself. That is the first principle of existentialism …….. Man will only attain existence when he is what he purposes to be)

Existence precedes essence

It was Plato who said that the surrounding world is a world of essences – ideas, values, ideals, thought etc. and the purpose of life is to discover these essences. Essences are already there and they precede existence. Even existence is an embodiment of an essence – the self, which is a part of an universal essence – the self.

, Existentialism is a revolt against any kind of determinism and an affirmation of the free nature of man. They affirm that existence is prior to essence that man is fundamentally free to create his essences .As Blackham writes, “There is no creater of man. Man discovered himself. His existence came first, he now is in the process of determining his essence. Man first is, then he defines himself.”

As Sartre himself explains his concept to us, “what is meant here by saying that, ‘existence precedes essence?’ “It means that, first of all, man exists, turns up, appears on the scene, and only afterwards defines himself. It mean, as the existentialist sees him is indefinable, it is because at first he is nothing. Only afterwards will be something and he himself will have made what he will be…”

Therefore, it can be easily observed that when idealists believe in transcendental values, Naturalists believe that values are resident in nature, pragmatists believe that values arise out of social life, existentialists affirm that the individual alone creates values. Reality is a state of becoming. Existence increases with every moment of life and essence is a consequence of this perpetual becoming.

Jean Paul Sartre’s classic formulation of existentialism–that “existence precedes essence”–means that there exists no universal, inborn human nature. We are born and exist, and then we ourselves freely determine our essence Some philosophers commonly associated with the existentialist tradition never fully adopted the “existence precedes essence” principle. Nevertheless, that principle is fundamental to the educational existentialist movement

Freedom is identical with existence

The existentialist concept of freedom is often misunderstood as a sort of liberum arbitrium where almost anything is possible and where values are inconsequential to choice and action. This interpretation of the concept is often related to the insistence on the absurdity of the world and the assumption that there exist no relevant or absolutely good or bad values

What is not implied in this account of existential freedom, however, is that one’s values are immutable; a consideration of one’s values may cause one to reconsider and change them. A consequence of this fact is that one is not only responsible for one’s actions, but also for the values one holds. Even though these are the values of the society the individual is part of, they are also his own in the sense that she/he could choose them to be different at any time. Thus, the focus on freedom in existentialism is related to the limits of the responsibility one bears as a result of one’s freedom: the relationship between freedom and responsibility is one of interdependency, and a clarification of freedom also clarifies that for which one is responsible

Individual freedom can be understood through the possibilities that an individual has. Therefore existential freedom cannot be absolute as it is always contextualised to the situation of each individual. Freedom is therefore inextricably linked to the notion of choice, in that one can choose from amongst one’s own possibilities. Once a choice has been made and acted upon, then one possibility becomes actuality, while other possibilities become negated. The dynamics of this interface between possibility, actuality and freedom of choice, is a major part of Existentialism.

An inherent aspect to this notion of freedom of choice, is responsibility. The existential perspective developed here considers that the individual who exercises personal freedom of choice must also be willing to accept responsibility for these decisions.. According to Sartre freedom is identical with existence. As such existentialism has even been described as a search for ways in which man’s freedom to create may be widely established and understood According to existentialists, man is not only free but he is condemned to be free. He is only not free, not to be free. This is the tragedy of human life. This infinite freedom entails upon him a heavy sense of responsibility and this situation of being burdened with a heavy responsibility is the cause of dread, anguish and anxiety. The peculiar quality of human reality is that it is without excuse. A bold, honest, responsible and authentic existence would help man to face this situation.

The most important of these characteristics is freedom. Man is condemned to freedom. “Human freedom is not a part of human existence, “ Sartre says, “it precedes human existence and makes it possible. The freedom of man cannot be separated from the being of man. It is the being of man’s consciousness. It is not a human attribute but is the raw material of my being. I own my being to my freedom.”

Man, then, does not possess free will as a part of his essential mature, but rather he exists in a state of absolute freedom. None of the environmental or hereditary forces are considered strong enough to impair man’s freedom. When a person selects a certain advisor or counselor, this very choice represents his freedom.

The most important characteristic to existentialist freedom, then, is that it is absolute. It does not consist, as some traditional philosophers hold, in the freedom to choose among alternative goods. Man has no guideposts by which to make his choice. He must simply make choices and these choice will determine his being. He is completely responsible for his own decisions and the effects they will have upon himself and others.

Reason

Existentialism asserts that people actually make decisions based on the meaning to them rather than rationally. The rejection of reason as the source of meaning is a common theme of existentialist thought,. Kierkegaard saw strong rationality as a mechanism humans use to counter their existential anxiety, their fear of being in the world: “If I can believe that I am rational and everyone else is rational then I have nothing to fear and no reason to feel anxious about being For Camus, when an individual’s consciousness, longing for order, collides with the Other’s lack of order, a third element is born: absurdity

The Absurd

The notion of the Absurd contains the idea that there is no meaning to be found in the world beyond what meaning we give to it. This meaninglessness also encompasses the amorality or “unfairness” of the world. This contrasts with “karmic” ways of thinking in which “bad things don’t happen to good people”; to the world, metaphorically speaking, there is no such thing as a good person or a bad thing; what happens happens, and it may just as well happen to a “good”.

Facticity

A concept closely related to freedom is that of facticity, a concept defined by Sartre in Being and Nothingness as that “in-itself” of which humans are in the mode of not being. This can be more easily understood when considering it in relation to the temporal dimension of past: One’s past is what one is in the sense that it co-constitutes him However, to say that one is only one’s past would be to ignore a large part of reality while saying that one’s past is only what one was in a way that would entirely detach it from them now. A denial of one’s own concrete past constitutes an inauthentic lifestyle, and the same goes for all other kinds of facticity

However, to disregard one’s facticity when one, in the continual process of self-making, projects oneself into the future, would be to put oneself in denial of oneself, and would thus be inauthentic. In other words, the origin of one’s projection will still have to be one’s facticity,. Another aspect of facticity is that it entails angst, both in the sense that freedom “produces” angst when limited by facticity, and in the sense that the lack of the possibility of having facticity to “step in” for one to take responsibility for one has done also produces angst

Anxiety & Alienation

Feelings of alienation can emerge from the recognition that one’s world has received its meaning from the crowd or others, and not from oneself, or that one is out of touch with one’s ‘inner self’. This latter notion is emphasised by Zohar and Marshall who argue that our present “personal and collective mental instability follows from the peculiar form of alienation associated with alienation from the centre – alienation from meaning, value, purpose and vision, alienation from the roots of and reasons of our humanity”..

.When Heidegger’s Dasein is confronted with the structure of its existence, it experiences angst - or anxiety. This experience individuates, it acknowledges the throwness by which one is in the world with its entities, including language and culture. He argued that that “What Angst is anxious for is being-in-the-world”, and yet is “nothing and nowhere” (Heidegger, 1996, p. 175). In angst, Dasein is anxious for itself. This individualizing experience lays before Dasein the choice of authenticity or inauthenticity as possibilities of its being:1

Angst

Angst, sometimes called dread, anxiety or even anguish is a term that is common to many existentialist thinkers. It is generally held to be the experience of human freedom and responsibility… It is this condition of absolute freedom in which man finds himself and the responsibility entailed by it hat creates the condition in man called anguish. Sartre describes this condition as one which necessarily arises when a man commits himself to a course of action fully realizing that he is deciding not only what he will be but also what effect his decision will have on others. Every decision adds something to one’s being; every decision affects other beings. The realization of this responsibility causes existential anguish. Sartre remarks that those who do not conceal it. They are in flight from anxiety which itself produces greater anxiety.

A second condition brought upon man by absolute freedom is abandonment. By abandonment, the atheistic existentialist means that since God does not exist, man is left to his own deserts in crating himself and the kind of world in which he will live. There are no apriority values according to which he can make his decisions; there are no transcendental codes of behavior; there is no moral law in “nature” to be discovered and followed by man. Since neither God nor the “natural law” exist, man cannot find any source out side himself by which he can judge his decisions or actions to be right or wrong – all is permitted. Men is abandoned to his own decision – he must do what he wills; he must create his own essence..

Despair

Commonly defined as a loss of hope Despair in existentialism is more specifically related to the reaction to a breakdown in one or more of the “pillars” of one’s self or identity.

What sets the existentialist notion of despair apart from the dictionary definition is that existentialist despair is a state one is in even when one isn’t overtly in despair:

Despair is another condition resulting from absolute freedom. Sartre describes this condition in these words. “it [despair] merely means that we limit ourselves to a radiance upon that which is within our wills, or within the sum of the probabilities which render our action possible.” Thus, when on makes a decision to act, he never can be sure what the result will be for himself or others. There is no certainty whatsoever that events will turn out as we will them. Nevertheless, one must make decisions and act in spite of all the uncertainty involved. Man must decide and act without hope. This willing and doing without any certain hope that what we wish or do will be as we would like it, is existentialist despair.

The condition of existentialist despair is important since it places upon each man the sole responsibility for creating his own essence. If he had some certainty that his decisions and deeds would have the desired outcomes, either in this life or the next, his freedom would be limited since actions would have a predetermined outcome. Under such conditions, the existentialist argues, both the world of events and man would be determined. This state of affairs, of course, would contradict the basic assumption of existentialism, absolute freedom.

Subjectivity (self consciousness)

According to existentialist, education should make a man subjective and should make him conscious for his individuality or ‘self’. Being self conscious he will recognise his ‘self’ and he will get an understanding of his ‘being’.

Individuality lies on self-realisation, a motivating force, which makes the inner life of man centre of concentration free from anxiety. There is a basic desire and inclination for the existence of individuality in man. It should be recognised. If this existential individuality is recognised, his life becomes purposeful and important. At the same time he becames conscious for his ‘self’

From an existential perspective, a sense of self-identity is gained by how an individual relates to and values his or her relations. Kierkegaard says, “ Because I exist, because I think, therefore, I think that I exist.” According to the statement ‘I think’ it is clear that ‘I’ exists and it has existence. ‘I’ that exists is always subjective and not objective. Now the person because of knowing the object does not desire to know the object, but he emerges himself in knowing the self. Subjectivity

According to Existentialism, individuals cannot understand their own being ontologically, because this requires knowing objectively what is. Kierkegaard’s claim that “subjectivity is truth” was not a declaration as to what ‘Truth’ in an absolute sense might be. He argued that such a claim clearly identified that his interest regarding human existence was not upon any ‘objective’ what, but rather it was upon how the individual made sense of and related to entities Existential subjectivity, sometimes referred to as inwardness, focuses upon the way that the individual believes, rather than the object of the belief..

Existential Crises.

The phenomenon of anxiety – as an important characteristic of the existential crisis – is regarded as a rarity and has been described as “the manifestation of freedom in the face of self Experiencing anxiety individuates, hence ‘death’ as an issue readily lends itself to this crisis because only oneself can die one’s own death

References

Ayer, A. J. (1990). The Meaning of Life and Other Essays. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press.

Chater, M. F. (2000). Spirituality as struggle: Poetics, experience and the place of the spiritual in educational encounter. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 5(2), 193-201.

Cooper, D. E. (1999). Existentialism: A reconstruction. (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Delors, J. (1998). Learning: the treasure within. (2nd ed.): UNESCO Publishing/The Australian National Commission for UNESCO.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1992). Interview: The 1920′s, 1930′s and the present: National Socialism, German history, and German culture. In D. Misgeld & G. Hicholson (Eds.), On Education, Poetry, and History: Applied Hermeneutics . Albany: State University of New York Press.

Gilliat, P. (1996). Spiritual education and public policy 1944-1994. In R. Best (Ed.), Education, spirituality and the whole child (pp. 161-172). London: Cassell.

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or Praxis. London, New York & Philadelphia: The Farmer Press.

Heidegger, M. (1996). Being and Time (Joan Stambaugh, Trans.). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Acknowledgements:

Dr Suraksha Bansal for being the scribe for this article

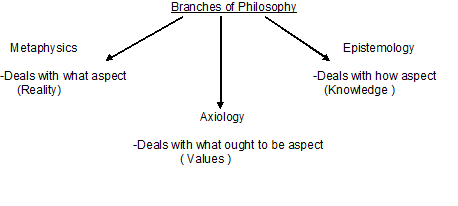

Science and philosophy have always learned from each other. Philosophy tirelessly draws from scientific discoveries fresh strength, material for broad generalizations, while to the sciences it imparts the world-view and methodological impulses of its universal principles. Many general guiding ideas that lie at the foundation of modern science were first enunciated by the perceptive force of philosophical thought.

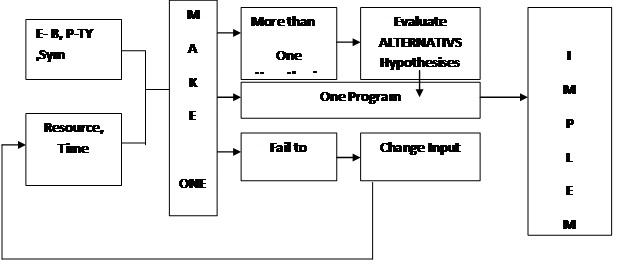

Science and philosophy have always learned from each other. Philosophy tirelessly draws from scientific discoveries fresh strength, material for broad generalizations, while to the sciences it imparts the world-view and methodological impulses of its universal principles. Many general guiding ideas that lie at the foundation of modern science were first enunciated by the perceptive force of philosophical thought. The recent transition to the information age has focused attention on the processes of problem solving and decision making and their improvement). In fact the strategies used in these processes to be a primary outcome of modern education. Although there is increasing agreement regarding the prescriptive steps to be used in problem solving, there is less consensus on specific techniques to be employed at each step in the problem-solving/decision-making process.

The recent transition to the information age has focused attention on the processes of problem solving and decision making and their improvement). In fact the strategies used in these processes to be a primary outcome of modern education. Although there is increasing agreement regarding the prescriptive steps to be used in problem solving, there is less consensus on specific techniques to be employed at each step in the problem-solving/decision-making process.

Existentialism is the most individualistic of all modern philosophies. Its overriding concern is with the individual and its primary value is the absolute freedom of the person, who is only what he makes himself to be, and who is the final and exclusive arbiter of the values he freely determines for himself. Great emphasis is placed on art, on literature, and the humanistic studies, for it is in these areas that man finds himself and discovers what values he will seek to attain.

Existentialism is the most individualistic of all modern philosophies. Its overriding concern is with the individual and its primary value is the absolute freedom of the person, who is only what he makes himself to be, and who is the final and exclusive arbiter of the values he freely determines for himself. Great emphasis is placed on art, on literature, and the humanistic studies, for it is in these areas that man finds himself and discovers what values he will seek to attain.